Types of Chinese Polearms and Their History

Chinese armies used a wide range of pole weapons in warfare. Polearms were easier to manufacture and didn’t require lengthy training to use. Some were solely designed for thrusting or cutting while others served as multipurpose weapons. There are several varieties of Chinese polearms, some of which are distinctive in form and called by different names.

Let’s explore the different types of Chinese polearms and how the infantry and cavalry used them.

Popular Types of Chinese Polearms

A polearm is a weapon with a pointed tip or blade fixed to a long shaft. Chinese polearms include several types of spears, dagger-axes, halberds, and glaives. Generally, a halberd is a combination of a spear and an ax while a glaive has a single-edged blade on the end of the pole. There were also several types of spades, forks, and tridents in the Chinese arsenal.

1. Spear (Qiang)

A spear generally refers to a long-shafted weapon designed for thrusting. The Chinese spear is called qiang (槍) and comes in various sizes and shapes. It was a more important weapon on the battlefield than the sword. Both the cavalry and infantry used spears as they needed extra reach in combat. The Chinese did not differentiate between spear and lance as both polearms are called qiang.

Some Chinese spears had hooked designs and had a variety of names. The gou lian qiang (鉤鐮鎗), meaning hook-sickle spear, had a sickle blade and was used by the Green Standard Army. Some also had two sickle blades on both sides, while others had small hooks protruding from the base of the spearhead. The hu ya qiang (虎牙槍), meaning tiger fang spear, featured teeth on the blade.

2. Dagger-Axe (Ge)

Dagger axes had a blade fixed perpendicular to a shaft, which could be as long as a spear. It was suited for hacking at an enemy and had to be swung to be effective. They emerged long before the chariots or cavalry became prevalent, suggesting that the weapon was not originally designed for dragging down a chariot passenger or a mounted warrior.

The name dagger-axe is the standard English translation for the Chinese word ge, and it should not be confused with the term halberd. It was a weapon unique to China, used from the Stone Age to the Zhou dynasty.

3. Halberd (Ji)

The Chinese halberd (ji) had both a dagger-axe and a spearhead mounted on a long shaft. It may have allowed tighter formations that relied on the spear point rather than the hacking point. In Chinese archeological terminology, ji is the standard term for halberd, though the ancient Chinese halberd did not resemble the medieval European halberd.

Some Chinese halberds are distinctive for their crescent-shaped ax blade fixed to the spearhead, and some variants even had two crescent-moon blades on both sides. However, they widely varied in blade shapes, including the snake halberd, horse halberd (ma ji), and so on.

4. Guandao

The guandao, also spelled kwan dao, is a Chinese polearm with a large blade similar to a European glaive. It is most recognized for its curved and scalloped blades mounted on a simple wooden pole. With the chopping power of a sword and the length of a spear, it was used when fighting on horseback.

The guandao was called by several names, including yanyuedao (reclining moon blade) and chunqiudao (spring-autumn blade). In modern times, the guandao is most associated with the Green Dragon Crescent Blade, the weapon of Guan Yu in the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. In martial arts, it remains popular in Shaolin kung fu and Chen-style taijiquan.

5. Podao

Another type of Chinese glaive is the podao (朴刀), featuring a cleaving blade with a flat tip. During the Ming dynasty, it was called zhanmadao (斬馬刀), meaning horse-cutting blade. As the name implies, it was a widespread weapon for chopping horse legs during battle.

However, the term zhanmadao referred to a wide variety of Chinese weapons, including the double-edged sword jiàn (劍) and the two-handed saber of the Qing dynasty.

6. Piandao

Similar to the Japanese naginata, the Chinese piandao has a slender, curved blade tapering to a sharp point. The Chinese polearm piandao, written in Chinese characters 片刀, should not be confused with the Qing saber of the same name, written as (扁刂). It was among the issued weapons to the Green Standard Army, who served as peacekeepers and auxiliary troops.

7. Crescent Moon Spade (Yue Ya Chan)

The crescent moon spade, also known as yue ya chan (月牙鏟), had an upward crescent blade. The famous Shaolin monk’s spade version typically had a crescent blade on one end and a shovel-shaped blade on the other end. Shaolin monks used spades to bury dead bodies they encountered on their journey which was part of their religious obligation. Eventually, spades became self-defense weapons.

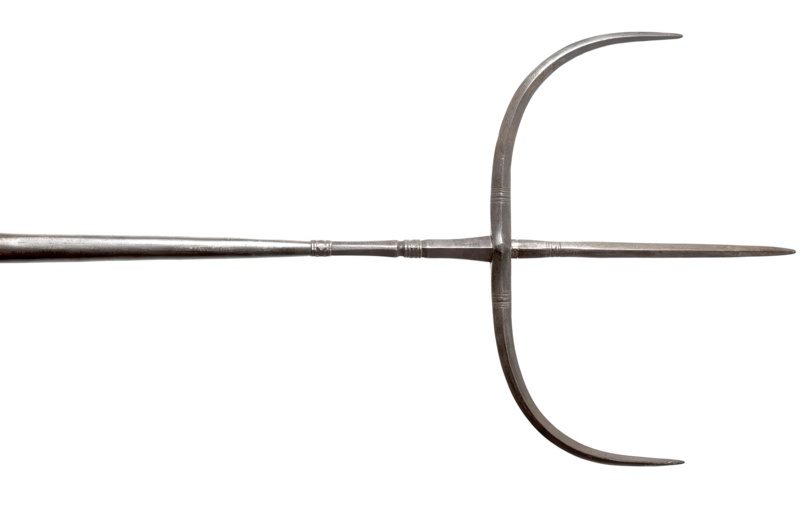

8. Tiger Fork (Hucha)

Also called hǔchā (虎叉), the tiger fork is most recognized by its trident shape, having a three-prong metal head on a shaft. It is thought to have been developed in Southern China to use against tigers and other large animals that posed a threat to local communities.

Eventually, tiger forks became a weapon for keeping enemies at bay and were used by Chinese soldiers, guards, patrol officers, and militia. There are also several fork- or trident-type weapons in the Chinese arsenal.

Historical Facts About the Chinese Polearm

It remains unclear how some Chinese polearms were actually used in battle, though their forms suggest their use. Some Chinese polearms, especially ones with double heads, served as cavalry weapons for slashing rather than thrusting.

- The dagger-axe served as a weapon of war

The dagger-axe probably developed from the sickle, a typical agricultural tool. Earlier types were dagger-like stones, but later ones were bronze-made, with heads fitted to a pole at a right angle. Unlike the axes, the dagger axes were designed for killing other men and are considered the first non-dual-use weapon of violence in Chinese history.

- Dagger-axe fighting was the typical martial art in ancient China

The skill of using a dagger-axe in battle seems to be the original martial art concerned with fighting other men. Despite other weapons becoming available, the dagger-axe was the typical combat skill. Soldiers likely had individual training in dagger-axe fighting rather than a group-oriented practice.

- Aristocratic men were skilled in wielding the dagger-axe or spear

Dagger-axe fighting can be traced back to individual fighting between aristocrats. Generally, most aristocratic men were trained in using the dagger-axe, driving the chariot, and shooting with a bow. The lowest-ranking man typically drove the chariot while the next-higher ranking man fought with a spear or a dagger axe. Then, the highest-ranking man used a bow.

- The shift from dagger-axe to halberd and spear had many advantages in combat

The infantry could fight more effectively in tight formation using their spear point facing out, unlike before when they needed more space to wield dagger axes effectively. Also, Chinese soldiers utilized the tip of their pole weapons rather than hacking at an enemy. The halberds and spears gave rise to mass warfare that consisted of commoners and the knightly class. There was also the departure of aristocratic dominance on the battlefield.

- The early Chinese halberd was a combination of a dagger-axe and a spear

Early bronze-headed halberds usually had a bronze spearhead and a dagger-axe as separate pieces on the same polearm. Eventually, iron halberd heads, with two points at right angles to each other were usually made in one piece, especially during the Spring and Autumn, and Warring States periods. The Chinese halberd was likely a transitional weapon between the spear and dagger-axe.

- Spear fighting was an important martial art for the military

Chinese soldiers had intensive training in spear fighting. Some believe that spear training would improve the overall fighting skills of a soldier. Also, soldiers were expected to fight in various circumstances that would need a broader range of spear skills. Spear fighting was also widely practiced outside of the military.

- Both the Chinese infantry and cavalry used spears in warfare.

The infantry used spears to fend off cavalry and chariot charges. On the other hand, the cavalry needed spears for the extra reach for stabbing down towards the infantry troops. Many cavalrymen who had excellent spear-fighting skills were officers. However, spear techniques would have varied between infantry and cavalry.

- Some Chinese polearms were used in martial dances

Polearm dances were widespread during the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. Oracle bone inscriptions refer to a dance called gaiwu (祴舞), which was likely performed with the dancers holding ge polearms. In historical texts, the character gai is sometimes written as jie (戒), which has the shape of two hands holding a ge (戈) polearm.

- Symbolic dagger axes were placed in high-status tombs

Dagger axes found in tombs served as the symbol of the man’s status as a member of the aristocracy and a warrior. A practical weapon was considered symbolic when it was too heavy or large to be used effectively in combat or made of precious material like jade. Jade dagger axes were found on the tomb of military leader Fu Hao, indicating her importance and wealth.

- Chinese polearms remain widely used in wushu or kung fu

Modern Chinese speakers usually use the term wushu (武術), meaning martial techniques, to refer to the Chinese martial arts in general. Recently, the Chinese government established wushu as the term for the competitive sports version of Chinese martial arts. The term kung fu seems to be the English term for Chinese martial arts. Today, the guandao and spear (qiang) remain popular in weapons training.

History of the Chinese Polearm

The Chinese used various types of polearms in different periods. The dagger-axes (ge) were widespread from the Stone Age to the end of the Spring and Autumn Period. By the Warring States period, the Chinese halberd (ji) and spears were the standard weapons of soldiers fighting in a group.

During the Shang Dynasty

During the Shang dynasty, from about 1600 to 1046 BCE, infantry battles used dagger axes and spears. The dagger-axe appeared after the simple wooden spears, though the former was a more important weapon on the battlefield than the other in the early Shang.

Dagger axes utilized swinging techniques in combat. So, the infantry battles of the early and mid-Shang were fought on foot and in open formation. After all, a tight formation of soldiers would have made them unusable. By the late Shang, the Chinese also used bronze spears.

During the Zhou Dynasty

By the Zhou dynasty, from 1046 to 256 BCE, larger numbers of infantry and chariots fought coordinated battles. Most infantry continued to use the dagger axes, though the Chinese halberds (ji) also became widespread.

The ji is generally considered a Western Zhou weapon, though it was also discovered in an early Shang tomb. The straight, double-edged Chinese swords, the jian, were also developed during the period. However, these swords were bronze-made and initially short.

During the Warring States Period

By the Warring States period, the Chinese halberd ji, spear, and sword gradually replaced the dagger-axe. While the infantry favored halberds and spears, chariot warriors likely continued using longer hafted dagger-axes for swiping attacks against other chariots and infantry.

Charioteers might have used spears to fend off infantry who tried to approach them, though the weapon would be inefficient from a moving chariot. When charioteers dismounted, they utilized swords for close-quarters combat.

During the Han Dynasty

During the Han dynasty, from 206 BCE to 220 CE, the Chinese halberd (ji) became the standard infantry weapon. Halberds were also used in sports and entertainment. The Hundred Events were competitions and performances of martial arts involving various weapons.

The Five Weapons (五兵) consist of a halberd (ji), spear, sword, long sword, and staff. However, some sources define the Five Weapons as the halberd, bow-and-crossbow, sword-and-long sword, shield, and armor.

During the Three Kingdoms Period

The Three Kingdoms were a trio of warring Chinese states: the Wei, the Wu, and the Shu-Han. The Chinese halberd was still in common use, though the long spear became more widespread. The cavalry from horseback used long spears to strike the infantry. As a response, the infantry also adopted long spears to increase their reach against the cavalry.

During Ming Dynasty

During the Ming dynasty, from 1368 to 1644, Japanese pirates made coastal raids in Chinese waters. General Qi Jiguang raised new military units from local militias and established proper martial arts training. Instead of fighting Japanese swordsmen individually at sword range, the Chinese troops used spears and other polearms to defeat Japanese swordsmanship.

In Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty, also known as the Manchu dynasty, spanned from 1644 to 1912. The Qing recorded several Chinese martial arts styles, including the Xingyi style, which developed from spear techniques. While spear fighting was appropriate for times of turmoil, such as the Qing conquest, boxing became more relevant for self-defense during peacetime.

In military examinations, the Qing military also used a heavy guandao called wǔkēdāo (武科刀). Heavier polearms generally helped in building strength during training, though they were not practical in actual combat.

During the 19th century, Western military technology and techniques were adopted into the Qing military. Chinese soldiers practiced some hand-to-hand combat skills, especially using rifles with bayonets. The traditional Chinese martial arts also became obsolete, as rifles and artillery became the battlefield weapons—not swords and spears.

Conclusion

Polearms were among the long Chinese weapons used in warfare. Some functioned as thrusting weapons while others were efficient for cutting. Some polearms such as dagger axes in tombs were symbolic and associated with aristocrats and warfare. Even though Chinese polearms became obsolete in military use, they remain relevant in wushu or kung fu.