An Insider’s Guide to Japanese Sword Appraisal and Valuation

The value of a Japanese sword is greatly influenced by its origin or provenance. Japanese sword appraisal is a specialized field that requires extensive knowledge and expertise in various aspects of swords. Experts determine when and where it was made, along with its swordmaking school or wordsmith.

Special thanks to Mr. Markus Sesko, an expert in Japanese Arms and Armor and a member of the NBTHK, the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords. He assisted me in discovering some details that I couldn’t find during my research.

Let’s explore the steps involved in Japanese sword appraisal, the factors that contribute to the value of a sword, and the official organizations that offer valuation services.

What Is Kantei and How Is It Done?

Kantei, meaning (sword) appraisal or attribution, is a process used to determine the age, swordmaking school or tradition, and the swordsmith of a blade. The Japanese blade is attributed to its maker based on its appearance, such as its overall shape, steel surface, and hardened edge.

Basically, any experienced sword connoisseur or collector can perform a kantei. However, in Japan, one must be certified to be called an appraiser or kantei-ka. This term also applies to appraisers of all kinds of antiques and arts, not just swords.

However, issuing an actual written appraisal (kantei-sho) is a different matter. Several dealers, clubs, and institutions issue such appraisals, but their credibility greatly depends on their track record in correctly attributing the sword to the right school or maker.

What Does Shinsa Mean?

In sword societies of Japan, shinsa refers to the formal sword appraisal or examination process where a group of judges performs kantei on the blade. These judges determine and define the authenticity and quality of Japanese swords. Typically, the number of judges in a shinsa is uneven to prevent a draw or tie when it comes to decision making.

The shinsa focuses on the quality and condition of the blade. While some Japanese swords may have flaws (kizu), they must not detract from the beauty and value of the blade. Some flaws may be overlooked, but those that cannot be fixed results in the sword having no value to collectors. Some swords may not pass shinsa if they are in poor condition, have poor polish, or bear a false signature.

The judges’ remarks on the blade are documented in an appraisal paper called kantei-sho. Some sources refer to these certificates as origami, but according to experts, the term origami is mainly used for period appraisals issued by the Hon’ami family.

Criteria for Japanese Sword Appraisal

Traditionally-made Japanese swords or nihonto possess artistic qualities. They are appraised based on their bare, unmounted blades. In sword appraisal, the overall shape of the blade, the surface steel, and the hardened edge are essential factors in determining their origin. Additionally, if the swordsmith’s signature is present, it is examined as well.

1. Sugata (Shape)

The sugata refers to the shape of the sword as a whole. Generally, a Japanese sword is single-edged and curved. However, it varies in blade length (nagasa), curvature (sori), width (mihaba), size and shape of the point (kissaki), central ridge (shinogi), unsharpened back surface (mune), thickness at the mune (kasane), bulging of the cutting surface (niku), grooves (hi), and engravings (horimono).

Japanese swords changed over time to adapt to military tactics and fighting conditions. Therefore, a sugata is a helpful indicator of a sword’s age and the period when it was made. Generally, the more strongly curved blades are older, usually before 1600, while later swords are less curved. The characteristic features of a sugata can also point to certain schools and swordsmiths.

2. Jigane (Steel Surface)

The jigane refers to the appearance of the surface steel of a Japanese blade, including its texture, color, visible forging structure or grain pattern (jihada), and other features. The jigane of Japanese blades varies in appearance due to the differences in the raw materials in each production area and period.

Also, different schools of swordmaking and lineage had their forging methods to create jigane. Therefore, the jigane helps identify the area of production or the swordmaking school of the blade.

The jigane also helps determine if a blade is a koto (old) or shinto (new). Generally, koto (old swords) are dark gray, while shinto (new) and shinshinto swords are lighter. Koto blades were produced from 1000 to 1600, shinto blades were made from around 1600 to 1790, and shinshinto were manufactured from 1790 to 1876.

3. Hamon (Hardened Edge)

The hamon refers to the visible pattern of the hardened steel along the cutting edge. It gives a Japanese blade its superior cutting ability and artistic qualities. There are several hamon patterns that are often associated with specific swordmaking schools or traditions, provinces, and trends of various periods.

The hamon features examined in an appraisal include the nie and nioi (large crystals and fine particles), activities (hataraki) on the hamon, border of the hamon (habuchi or nioiguchi), and others. Also, the hamon on the point area (boshi) is a good indicator of the overall quality of the blade.

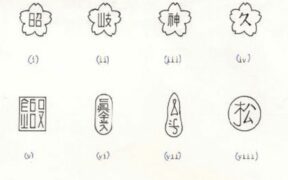

4. Mei (Signature) and the Tang

Not all Japanese swords are signed, as a swordsmith only signs those blades that meet his standards. Generally, a signature (mei) on the tang is a smith’s name, though it often includes other information such as his title, the town, and the province where he worked. Sometimes, the date of manufacture is inscribed on the opposite side of the tang from the smith’s signature.

However, forgeries are common, so a sword should never be appraised by its signature alone. To authenticate the signature and date the blade, sword appraisers also examine the rust on the tang and the file marks (yasurime). The yasurime refers to the decorative file pattern on the tang, and different file marks are attributed to individual swordsmiths, schools, and periods.

Appraisal of Newly-Made Japanese Swords

Both kantei and shinsa are applicable only to old or antique blades. The quality and value of newly-made Japanese swords are directly linked to the ranking of the swordsmith. The NBTHK organizes annual swordmaking competitions, and the more awards a swordsmith wins, the more valuable their works become.

If a swordsmith consistently wins one of the highest awards each year, the NBTHK gives the smith the rank of Mukansa (without supervision), making the individual officially above the regular ranking systems. Therefore, this smith can submit their works to the annual competition without being judged. This also ensures that upcoming smiths have a chance to win awards, so it would not be the same smith that wins every year.

Organizations That Perform Japanese Sword Valuations

Official organizations in Japan offer sword appraisal, authentication, and valuation services. However, different organizations have different systems of ranking swords, and the blade’s score and designations are essential factors in determining a sword’s value.

1. NBTHK (Nippon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai)

The Nippon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai (Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords) performs shinsa, or sword evaluation and appraisals. It registers Japanese swords as art objects and cultural assets according to their origin and qualification.

Works of art worthy of preservation also include sword mountings and ornaments, such as koshirae (functional traditional mounting) and its components like the tsuba (sword guard), fuchi and kashira (collar and pommel cap), and so on.

More commonly known outside of Japan, the NBTHK sword designations include Hozon (Worthy of Preserving), Tokubetsu Hozon (Worthy of Special Preservation), Juyo Token (Important Sword), and Tokubetsu Juyo Token (Particularly Important Sword).

Swords and sword fittings evaluated by the NBTHK could receive appraisal papers (kantei-sho) stating the judges’ opinions regarding their quality and value. The NBTHK also offers membership, and there are corresponding shinsa fees for both members and non-members.

2. NTHK (Nihon Token Hozon Kai)

Highly respected in Japan, Nihon Token Hozon Kai (NTHK) is an official organization performing shinsa on Japanese swords. The NTHK also conducted several appraisal sessions in the US to meet the needs of Western collectors.

The NTHK determines the score for the blade, which determines its designation. NTHK sword designations include Shinteishi (Genuine), Kanteisho (Fine Quality), Yushu-Saku (Superior and Excellence Rank), and Sai Yushu Saku (Highest, Superior, Excellent Rank).

Generally, those who wish to submit swords and sword fittings for shinsa must make reservations for the event. Apart from the submission fees, blades passing shinsa will also incur additional mandatory fees for the formal appraisal papers (kantei-sho), which will be sent to the owner from Japan.

The NTHK’s appraisal paper includes details such as the swordmaking school, registration number of the sword, type of sword (katana sword, wakizashi, tanto), historical period the sword was made, the sword’s signature if present (and whether it is fake or not), blade measurements, and other information.

National Treasure Japanese Swords

The Ministry of Education has its own classification system for Japanese swords which are important cultural assets. The designations include Juyo Bunkazai, formerly Juyo Bijutsuhin (Important Cultural Item) and Kokuho (National Treasure). Japanese swords with these designations are heavily regulated and not allowed to leave Japan. This means that most collectors will only see such blades in a museum.

Many swords that originated from the Heian to the Edo period are masterpieces made by famous swordsmiths, including Masamune of Sagami (present-day Kanagawa Prefecture). Many are also of particular historical importance. For instance, some were previously owned by Japanese samurai Toyotomi Hideyoshi, shoguns Tokugawa Ieyasu, Tokugawa Hidetada, and such.

Conclusion

A fine Japanese sword must be structurally sound and aesthetically pleasing. In Japanese sword appraisal, experts determine if a sword is a particularly good example of a particular swordsmith’s work. A high-value blade should also have some historical significance, such as being associated with known previous owners or being documented in historical records belonging to a household or shrine.