Jigane: The Surface Steel of the Blade

The jigane is the surface steel of a Japanese blade that dictates the quality of the sword. It has a definite color and texture that can help identify its sword making school, smith, or whether it is an old or new blade. Let’s explore the characteristics of jigane, its notable features, and why it is a crucial factor in sword appraisal.

What Exactly Is Jigane?

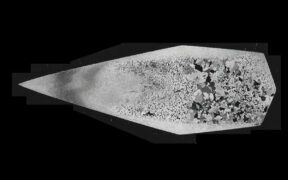

The jigane (地鉄) refers to the visible surface steel of a Japanese blade. The terms jigane and jitetsu refer to the appearance of the surface steel, including its color, texture, pattern, and other features.

The jigane helps determine whether a sword is of good or poor quality, or if it is a koto (old) or shinto (new) piece. For old blades, the appearance of jigane may reveal its origin, sword making school, and swordsmith.

In a sword appraisal (kantei), the jigane may be strong, weak, clear, cloudy, dull, or whitish. When describing its appearance, the jihada (grain pattern) and other blade features are also described.

Characteristics of the Jigane

The jigane is the steel on the surface of a Japanese sword. Its appearance varies greatly, usually in color, texture, pattern of forging structure (jihada), and other features. Here are the unique characteristics of the jigane and the Japanese terms used to describe its features:

Structure and Composition

In Japan, the traditional Japanese steel tamahagane is used as raw material for making sword blades. Modern-day swordsmiths make their own material or purchase tamahagane from the NBTHK. The exact appearance of the surface steel of a sword, the jigane, is under the artistic control of the swordsmith. Generally, a high-quality jigane is produced with skillful hammering during forging.

The varying appearance of the jigane in historical blades was due to differences in the raw materials in each region of manufacture and period. Each sword making school and lineage had its methods of forging to create jigane. Also, a tight steel surface is the result of proper forging. There should be no gaps, pockets, or separations in the steel.

Features of the Jigane

The jigane has notable features, from its color to grain patterns (jihada). Its texture is also influenced by some activities within and along the hamon (temperline pattern) and the blade’s body (ji).

Color of the Steel Surface

Traditionally forged Japanese steel usually appears dark—not bright or reflective, unlike the bright, shiny blades made of factory steel. The color of the jigane may be uniform or patchy. It may also show reddish, yellow, blue, purple, and black hues which results from the forging and hardening methods the smith used. Also, old swords tend to be darker, while new blades tend to be lighter.

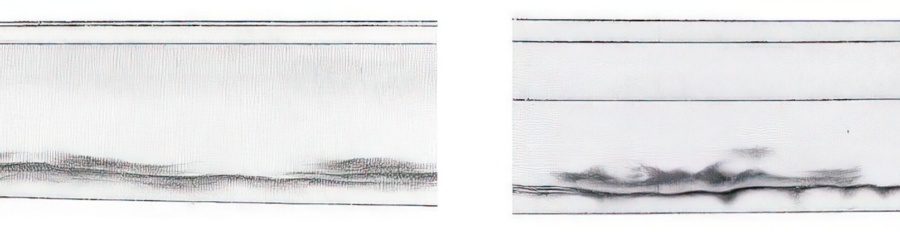

Jihada (Grain Pattern)

The jihada is the grain pattern within the steel, resulting from the repeated folding of the steel during forging. It appears as intricate patterns, such as masame (straight grain), mokume (wood pattern grain), itame hada (plank pattern grain), nashiji (pear skin grain), and ayasugi (undulating wave grain). Some blades feature one type of grain, but a blade often features a mix of grain patterns.

A jihada can be very clear or nearly invisible. When examining the jigane, the more uniform the jihada is, the better the swordsmith’s skill. Even if a blade has different grain patterns, these areas should never appear unnaturally. For instance, a blade with a tight hada must not be very coarse, rough, or diverse in one area, as it suggests that the smith lacked skill.

Still, some appearances of the jihada may be the unique characteristic of a certain swordsmith or school. The uniformity and fineness of the jihada suggests that the blade is of high quality. Still, it does not necessarily mean that a larger, structured jihada is of lesser quality. Prefixes ko– and o– describe its smaller or larger size, respectively, such as ko-itame (small itame hada).

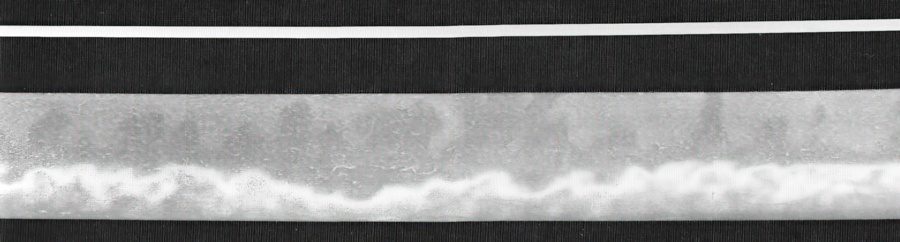

Ji-nie (Formations of Large Crystals)

The most common feature of the jigane is the ji-nie (地沸). The ji-nie refers to the formations of the large nie (martensite crystals) in the blade’s body (ji). The nie appears as dots or islands and is mainly seen along or above the hamon (temperline pattern).

The ji-nie can be fine and evenly distributed throughout the blade or concentrated in certain areas. Generally, a high-quality ji-nie is fine and uniform. Still, some styles are intentional, especially if a smith designed it to be rough and obvious.

Sometimes, the formations of the ji-nie may appear like drops of water or stain and may be described as yubashiri or jifu. Depending on the condition of the sword blade, these features might not be visible.

Yubashiri

The formations of ji-nie may appear like water droplets and are called yubashiri (湯走り), which literally means “running hot water”. They are common on Kamakura-era Yamato, Yamashiro, or Soshu blades.

Jifu

Sometimes, the formations of ji-nie give the blade a spotted appearance. The jifu (地斑) refers to the areas of dense ji-nie, which appear as splotches, stains, or spots on the blade’s surface.

Chikei (Black Lines)

The chikei (地景) refers to the black lines or patches in the blade’s body (ji). On the other hand, the black lines inside the hamon are called kinsuji. These black lines are layers of steel with different, higher carbon content.

These black lines generally follow the layer structure of the jihada (grain pattern). A blade with more chikei more often suggests that it was forged following the Soshu tradition, which intentionally mixed steels of varying carbon content.

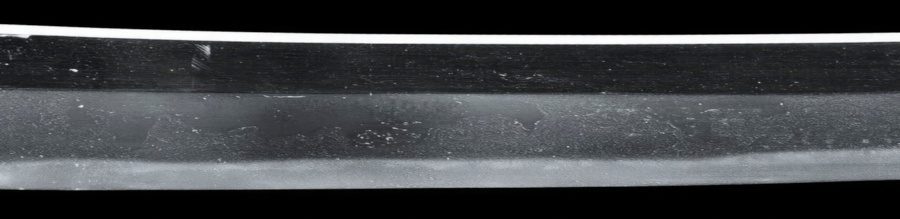

Utsuri (Reflection)

The term utsuri means “reflection”. It is a visible reflection on the blade’s body (ji) that runs parallel to the hamon (temperline pattern). There are several forms of utsuri, ranging from straight to round patches. Different forms of utsuri are associated with various sword making schools and historical periods.

Appearance of the Jigane

The appearance of the jigane can be described as tsuyoi (strong), yowai (weak), sunda (clear), nibui (dull), nigotta (cloudy), shiraketa (whitish), and such. Generally, its appearance is associated with various schools of swordmaking and historical periods.

Tsuyoi (Strong)

A jigane is strong (tsuyoi, 強い) when the jihada (grain pattern) is very visible and has lots of ji-nie. Blades with a strong jigane are usually associated with the Soshu tradition.

Yowai (Weak)

The opposite of a strong jigane is a weak (yowai, 弱い) jigane. A weak jigane has a barely visible jihada and only has little to no ji-nie. Generally, shinshinto blades (made from 1600 to 1790) have a weak jigane, as not much is visible in their steel. However, exceptions are the works of some smiths like Koyama Munetsugu and the Kiyomaro school that revived the strong Soshu jigane.

Sunda (Clear)

The steel can also be clear and described as saeru (冴える), or the Japanese equivalent term sunda.

Shizunda (Subdued)

The steel can also be subdued (shizunda, 沈んだ) and can be described as dull (nibui, 鈍い) or cloudy (nigotta, 濁った). A dull or cloudy jigane means that the steel surface remains matte even if it is polished. Even if a polisher tries to enhance the sword’s body with some polishing methods, a dull or cloudy steel will never become super bright.

Shiraketa (Whitish)

A whitish jigane is called shiraketa, also referred to as shirakeru. Generally, the steel can be distinguished between whitish (shirake, 白け) steel or blackish (kuroi, 黒い) steel. Blades of the later Mino school are known for showing much shirake.

Facts About the Jigane

The Japanese sword’s appeal as an art form is derived from its features, especially the blade and the steel surface (jigane) itself. Unlike other swords, Japanese swords are examined and appraised based on their bare, unmounted blades.

The jigane is among the factors examined in a sword appraisal.

A sword appraisal is called kantei, and it observes all the workmanship of the sword. There are 13 factors (jusan no mitsuke) observed, and the steel material (jigane) and grain pattern (jihada) are among them. Generally, it is only possible to create a strong, hard blade with a good jigane.

The rest of the criteria include blade shape (sugata), curvature (sori), temperline pattern (hamon), the temperline of the point (boshi), and kaeri of the boshi, unsharpened back surface of the blade (mune), color of the blade’s body (ji-iro); nioi and nie crystalline particles, color of hardened steel along the cutting edge area (ha-iro), line along the blade’s length (shinogi), and decorative carving (horimono).

A polisher refines the jigane and brings out other features of the blade surface.

Polishing a Japanese sword is as complex as making it. The steel has a bit of a dark appearance, so a polisher must bring out all the details in the steel surface, including the jihada (grain pattern) and hamon (temperline pattern) while making a functional blade. A polisher also makes the sharp edge and refines its shape.

The polish of the blade affects the appearance of the jigane.

The appearance of the jigane can be influenced by several factors: the age of the blade’s polish, the polisher’s skills, and the methods to finish the blade’s body (ji). Generally, the grain pattern (jihada) and its density are observed regardless of the finish of the polish. A well-polished blade makes its color and fine texture visible. When the polish is bad or too old, it may not be possible to examine the details in the steel.

The jigane is different in all sword making schools and historical periods.

The smiths from the Hokkoku region—comprising Noto, Sado, Kaga, Echizen, Echigo, Etchu, and Wakasa provinces—were known for producing blades with a blackish jigane. The Yamashiro, Yamato, and Bizen blades also had a well-forged jigane, each with characteristic grain patterns. On the other hand, a cloudy jigane (kumori-gane) was seen on some blades of the Nio school.

Koto blades tend to be darker in color, while Shinto and Shinshinto blades are lighter.

Koto (old) blades were made from 1000 to 1600. Many high-quality blades from the Kamakura period were fine, dark-gray velvet. On the other hand, later swords tend to be lighter. Shinto (new) blades were produced from around 1600 to 1790, while Shinshinto (new-new) blades were made from 1790 to 1876.

The Japanese saying jigane ga deru means the steel appears.

There are some sword-related Japanese sayings, such as jigane ga deru (地鉄が出る), which translates as the steel appears. It is especially true when the blade is polished, and the jigane shows more unrefined areas. This expression means to reveal one’s true character.

Conclusion

There are several reasons to appreciate the Japanese sword, and one of them is the jigane. The Japanese sword steel is typically darker in color and has a visible texture, with the jigane playing a crucial role in determining the blade’s quality, identifying its area of production and school, and thus being a vital factor in sword appraisal.