The Role and Craft of the Togishi in Japanese Swords

The togishi (研師) or sword polisher has played a crucial role for many centuries in Japan. Their laborious craft can take several days or weeks to complete depending on the condition of the sword.

With time, the art of Japanese sword polishing has gained much recognition and prominence. We explore the togishi’s role, craft, and how it has evolved throughout history.

What Does the Togishi Do?

As implied, a sword polisher polishes the sword. However, this is much more complex in Japanese swords as a togishi continues to sharpen and clean the blade.

Using their tools, they make the details of the sword smith’s metalwork stand out – resulting in an attractive blade. This means that they define the lines on the blade by:

- Bringing the hamon (temper line) to life

- Enhancing the jihada (grain of the steel)

- Accentuate the jitetsu (color and texture)

- Burnish the top and back to give it a mirror finish

In Japanese literature, polishing is akin to “expressing the true character of the sword” or to “expose its heart”. Due to their specialty, they also played a role in sword appraisal.

The Polishing Process

The forging and hardening process leaves a mark on the blade. These marks would be easily visible if the surface is smooth. However, the polishing stones used leave some scratches on the surface.

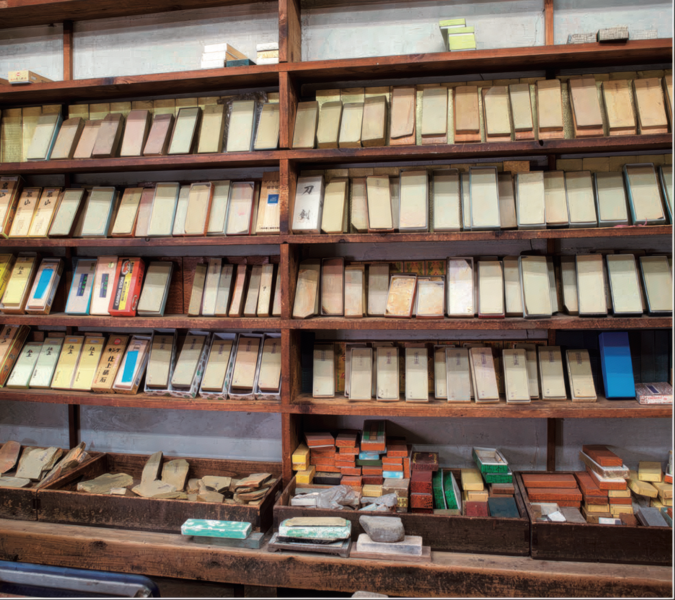

This means that the togishi will use a gradual series of stones, from the coarsest to the finest so the scratches left by the last stone is smaller than the structural variations in the steel.

Pre-Polishing

Before the polishing process begins, the togishi must observe the sword and surmise what period an antique sword is from or in a new sword, the tradition it represents.

They must consider what sword they are dealing with by answering the following:

- Who the sword maker was

- Characteristics of the maker and their school

- The hamon design

- Shape of the blade point

- Quality of the metal

- And more

In old swords, the togishi has to develop a feel for the metal of different periods. The difficulty in removing scratches is an indicator of how hard the steel is, its quality, and origin.

For example, 16th century swords from the Bungo Takada region remain cloudy even after polishing. This may seem inferior to the inexperienced eye and further attempts to bring out its details can ruin the blade.

A togishi also has to learn when a blade has had enough. For example:

- An old sword where further polishing will remove the hamon

- A nick in a sword’s edge where removing will destroy the hamon

The Togishi’s Working Position

For anyone unused to it, the working position of a togishi is immensely uncomfortable. Sitting on a low stool and hunched forward, they push the blade across the polishing stone.

Essential is a fumaegi, a curved piece of wood with one hooked end to clamp the polishing stone to the work block. This clamp is easily removed by lifting the right foot when polishing stones need to be replaced.

With the right heel pressing down on the fumaegi , the right knee is wedged into the right shoulder. Meanwhile, the left foot is curled under the body to prevent the fumaegi from moving. For safety reasons, the edge of the blade always faces away from the body.

Although awkward, this positions the toshigi directly over the stone to precisely control the direction, pressure, and angle of the blade. A bucket of water is always nearby as a lubricant.

Polishing Stages

Japanese sword polishing is divided into two stages: shitaji togi (foundation polishing) and shiage togi (finish polishing).

Shitaji Togi

This is the most important stage in blade restoration and repair. Before any polishing begins, the togishi inspects the sword to see if it is straight. If not, it must be corrected using wooden jigs.

In this stage, coarser polishing stones are used, making precise control of the blade essential to prevent deep scratches. The stones in order are: arato, binsui, kaisei, nagura, and uchigumori. Any bohi (fullers) will be polished using smaller stones as well. Note that the blade is moving during the polishing process at this stage.

Shiage Togi

In the second stage, the stones used are much thinner and backed with paper and lacquer. It starts with hazuya, jizuya, nugui, and hadori.

These stones held in the hand are moved over the blade to create a mirror-like finish. Note that the blade remains stationary in this stage as opposed to the first stage.

The special nugui compound is applied to balance the blade’s texture and appearance. Polishing concludes after defining the point, whitening the hamon using a hadori stone, and burnishing the back and upper sides.

Differentiating Between A Good and Bad Polish

A good polishing reveals all the features of the blade clearly. This is essential so the sword can be fairly appraised. In contrast, a poor polish may produce a clean blade, but with details that are cloudy. This makes appraisal of the sword much more difficult and can bring down its value.

History of Japanese Sword Polishing

Sword polishing was already in practice when chokuto were being used. However, the evolution of sword polishing in Japan is difficult to trace as steel always rusts. The general rule is that a good polish lasts no more than a hundred years. For this reason, no one really knows what sword polishing in the Kamakura or Muromachi Period was like as they have been polished in more recent times.

It is believed that swordsmiths originally did the rough polishing to complete the blade’s final edge and shape using the roughest stones: arato, binsui, and kaisei.

- Kamakura Period: Polishers work separately from smiths using most of the stones today.

- Momoyama Period: Polishers also serve as appraisers due to their knowledge of styles and quality. The most prominent being the Hon’ami family established by the warlord Hideyoshi in the 16th century.

- Meiji Era: People were not allowed to wear swords, but permitted to own them as works of art. This resulted in an increase of sword owners and thus, improvement in polishing techniques. The invention of the electric light bulb also allowed togishi to work more hours, accelerating the development of the hadori style as the hamon is more visible with light.

Sword Polishing Schools in Japan

Today, there are two main sword polishing schools in Japan. One being the Hon’ami family mentioned above and the other, the Fujishiro family. Both schools differ in training and finishing techniques:

- Hon’ami – Known for their 18th century compilation of Japan’s finest swords (Kyoho meibutsu cho), they are more strict about form and discipline. This includes how the student sits, holds the blade, and the pace one masters the stones’ progression. Students spend two years on foundation polishing and another two years on finish polishing before they are permitted to polish a blade from start to end.

- Fujishiro – They are far more relaxed and allow their students to progress rapidly from one stage to the next. This is based on the belief that asking students to spend too much time on basics may be discouraging. Since errors in polishing do not show till the later stages, students are asked to work on a blade from start to finish to learn where their mistakes occur.

There are about 50 togishi in Japan today. Although there is no standard qualification system, one must apprentice under a master or attend class to gain advanced skills.