Scimitar vs Sabre Swords: What Are the Main Differences?

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Scimitars and sabres are some of the most commonly discussed swords in the sword community. Due to their shared traits such as having a single-edged, curved blade, they are often confused with each other.

Despite their similarities in appearance, they differ in their origin, design, use, and historical impact. This article delves into these differences—comparing their characteristics, combat effectiveness, and historical impact.

Definitions

The term “scimitar” is an umbrella term used for single-edged curved swords originating in the Middle East. It encompasses sword types such as the Turkish kilij, Persian shamshir, African Nimcha, Arabic Saif, Indian tulwar, and Afghan pulwar.

Meanwhile, the term “sabre” refers to a group of swords used in Europe after the 18th century. These swords are characterized by single-edged blades with a curvature, though in rare instances they can be straight.

Design Differences

The biggest difference between an Eastern scimitar and a Western sabre is the curvature of the blade. Scimitars tend to have a more pronounced curvature, with its tip rising above the hilt-line. Some scimitars also feature a yelman, a broadened tip designed for powerful slashing.

On the other hand, sabers generally have a blade with a gentler curve and may include a double-edged tip, known as a false edge.

Scimitars tend to have an open hilt design which may include an L-shaped pistol grip or “wolf handle”. A lanyard may also be attached, allowing the scimitar to be secured around its wielder’s wrist. In comparison, sabers generally have a protective guard, which can be a complex basket hilt or simple knuckle guard.

When it comes to sheathing mechanisms, both swords are carried on the user’s left, hanging off a belt or a strap. However, scimitars often have a unique interlocking system or an opening on the side to accommodate the more pronounced curved blade.

Combat Preference

The scimitar was predominantly used for cutting and light thrusting. They are very fast and agile weapons that rely more on the user’s skill rather than their physical strength. While useful for infantry combat, its abilities shine on horseback as the curve of the blade combined with the momentum of a horse inflicts deep slashes without becoming lodged in the enemy.

Comparatively, European sabres are mostly cut-and-thrust weapons due to their gentler curve. This makes them suitable both on foot and on horseback. Also nimble and quick, sabers are easy to carry and rely on the user’s agility, excelling against unarmored opponents to create a significant wound while allowing the user to wield a pistol in the other hand.

Historical Significance

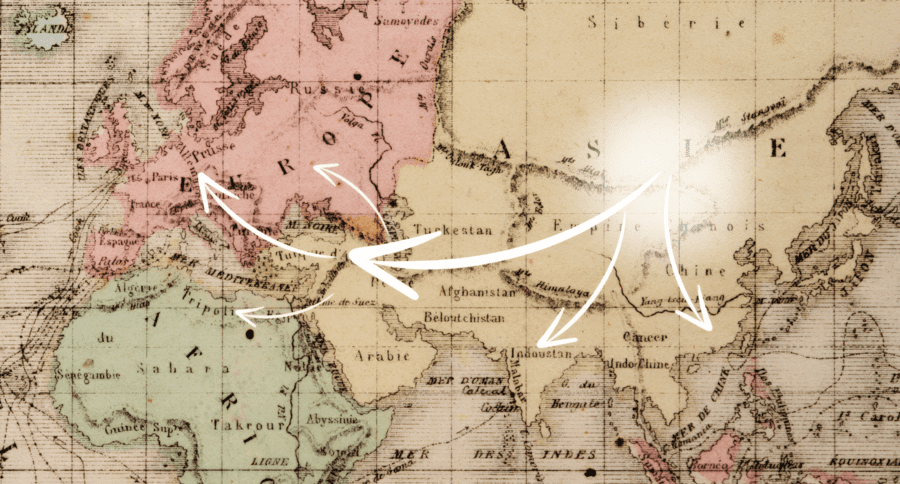

Both the scimitar and sabre trace their origins to the Turko-Mongol saber, which may have existed as early as the 7th century, possibly influenced by Chinese dao swords. This design spread with nomadic tribes and mercenaries such as the Avars, Mongols, and Seljuk Turks, eventually reaching India, Persia, and later Europe.

The first European sabres appeared in Eastern Europe as early as the 13th century, with most notable examples from areas such as Hungary and Poland. These blades eventually replaced the double-edged swords in Europe after the 18th century due to their ease of use and the decline of heavy armor.

Historians and HEMA instructors George E. Georgas and Nicholas Petrou say, “From the 13th century, Byzantine iconography increasingly depicts a sword with a distinctive single-edged blade”.