What the Nakago’s (Tang) Condition Reveals About Japanese Swords?

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

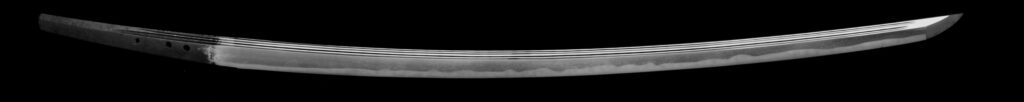

The condition of the nakago, the sword tang, is crucial in sword appraisal. Blade shortening was very common in Japanese swords due to the high cost of steel. Radical changes in fighting styles and the Tokugawa sword regulations led to the shortening of many fine old swords. To preserve the tempering of the blade’s tip, the shortening was always done on the tang.

The Practice of Blade Shortening—and How It Alters the Tang

Blade shortening on the tang has been a practice as old as sword making, providing a more cost-effective means to repurpose a fully functional blade into a shorter sword compared to creating a new one from scratch. Old swords were often shortened to suit evolving fighting styles, transitioning from use on horseback to use by soldiers on foot. Additionally, the Tokugawa government implemented regulations on allowed sword lengths that people could legally wear.

The tang, known as the nakago, is where the swordsmith signed his name. Blades that still bear their original signature (mei) are called zamei. However, when swords were shortened, the original tang and signature (mei) were often lost.

When a Japanese blade has no signature, it is either because the blade was not originally signed by its swordsmith, or because the signature was lost during the shortening process. A blade without signature is called mumei. In some instances, the signatures (mei) are partially preserved by various means.

When a blade is shortened, a new peg hole (mekugi-ana) is made. Sometimes, the signature is damaged by the addition of this peg hole. Each time a blade is altered, the number of peg holes increases. Sometimes, unused holes are inlaid with copper, silver, or gold.

Apart from the mei, the nakago features several details examined in sword appraisal. The shape of the tang, the butt end of the tang (nakagojiri), and yasurime (file marks) provide information about the blade, making them crucial in determining the sword’s age and attribution.

The Various Conditions of a Nakago

A Japanese sword may have an unaltered tang or a shortened nakago. The signature (mei) on the tang is one of its most important features and is often preserved when a sword is shortened.

Here are the various conditions of a Japanese sword tang:

1. Ubu Nakago

An ubu nakago refers to an original, unshortened, or unaltered tang. It is still shaped the way it was created by the swordsmith. It also implies that the tang’s butt end (nakagojiri) and notches (e.g. hamachi and munemachi) are in their original location.

In some cases, a Japanese sword can still be called ubu even if the tang’s curvature has been slightly reshaped, altered, or extra peg holes (mekugi-ana) added because of remounting as long as the blade’s length and shape are only slightly changed.

2. Suriage Nakago

A suriage nakago is a shortened tang. If there’s a signature (mei), it may be partly preserved. During the shortening of the tang, the notches (e.g. hamachi and munemachi) are adjusted higher up the blade. During the Muromachi period, the uchigatana-type sword or katana was preferred for its quicker combat response. Therefore, many tachi were converted into katana by shortening the tang.

Despite having a suriage nakago, a fine tachi nicknamed Okada-giri (which translates as Okada Slayer), made by Bizen swordsmith Ichimonji Yosifusa, is designated as a National Treasure. At the Battle of Komaki Nagakute in 1584, samurai Oda Nobukatsu used it to kill his retainer Okada Sukesaburo Shigotaka, hence its name. The sword features a pronounced curvature and wide blade, and is regarded as a testament to the artistry of all of Yoshifusa’s works.

Tachi-Mei

Tachi, worn with the cutting edge faced down, have their mei located on the side of the nakago that faces outward when the sword is worn. Most swords (excluding wakizashi and tanto) produced during the Muromachi period feature tachi-mei. Exceptions include swords made by swordsmith Yukihira and those of the Ko-Aoe school, as they signed their mei on the inner side facing the body when the tachi was worn.

Katana-Mei

The katana, along with wakizashi and tanto, were worn with the cutting edge faced upwards. Therefore, the katana-mei is located on the side of the tang that faces outward when the blade is worn. Swords produced after the Muromachi period often have katana-mei. However, exceptions include swords made by swordsmith Yamashiro no Kami Kunikiyo and those of the Tadayoshi and Suishinshi school as they inscribed their works with tachi-mei.

3. O-Suriage Nakago

An o-suriage nakago refers to a greatly shortened tang. If the entire nakago is lost during the shortening process, it is called an o-suriage-nakago. It is formed from what was originally part of the blade. Sometimes, a groove known as hi may extend into the nakago due to shortening, though it can also be intentionally created by the swordsmith.

If there was a signature (mei), it is usually completely lost. Many fine Japanese swords from the Kamakura and Nanbokucho periods are unsigned as their signatures were lost due to the shortening process. In some cases, the signature can be preserved by bending the metal bearing the mei into the newly-shortened nakago (orikaeshi-mei) or by resetting it in a new tang (gaku-mei).

4. Machi-Okuri

A machi-okuri describes an original tang, but its notches or machi, such as hamachi and munemachi, are moved upwards. It is done to slightly shorten the blade from the tip (kissaki) to the notches (machi) while extending the tang (nakago); therefore, the overall blade length does not change because the tang is not cut down.

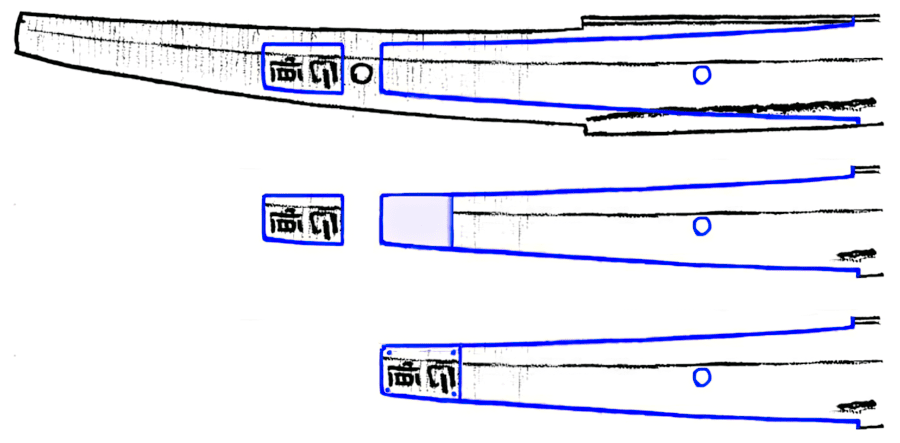

5. Orikaeshi-Mei

The signature (mei) on a Japanese blade is one of its most important features and is often preserved when the blade is shortened. Orikaeshi-mei literally means folded-over signature or turned-back signature.

When a tang is shortened, the portion bearing the signature is thinned down and bent around to the opposite side of the newly shortened tang. This allows the original signature to be preserved, but then appears upside-down on the opposite part of the nakago.

It is recommended to have an accurate drawing of the blade (oshigata) or rubbing of a signature when assessing its authenticity as discrepancies are more noticeable in an oshigata than on the actual blade. Generally, a long piece of rubbing paper should be folded at the tang’s butt end to cover both sides of the nakago.

Then, take a rubbing on both sides of the tang—both the unsigned and the part with the signature. Finally, flatten out the paper and view both sides as a whole. This approach makes it easier to determine whether the tang is bent or if the mei is in an impossible position.

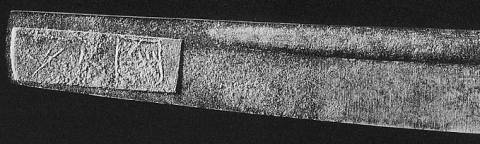

6. Gaku-Mei

Gaku-mei literally means framed signature. When a blade is greatly shortened (o-suriage nakago), the metal portion bearing the signature is cut out in a rectangular shape, thinned, and then re-attached to the new, altered tang.

Gaku-mei is another way of preserving the original signature on the tang even after shortening the blade. Another name for this kind of signature or process is tanzaku-mei because the cutout signature resembles tanzaku, or small vertical poem cards.

7. Hari-Mei

Hari-mei literally means patched signature. It is also known as haritsuke-mei. When a blade is greatly shortened (o-suriage nakago), the metal portion containing the signature is cut out and re-attached to the new, re-shaped tang via small rivets. It is an effective way of preserving the original signature, as gaku-mei can fall out over time.