Unveiling the Types of Greek Swords

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Early Greek warriors used a variety of swords which rose and fell in popularity due to evolving battlefield tactics and advancements in metallurgy. Let’s delve into the various types of Greek swords, from the early bronze weapons of Aegean warriors to the iconic swords associated with Hoplites and Spartans.

1. Bronze Aegean Swords

During the Bronze Age, Aegean warriors used different swords that varied in length, blade forms, and hilts.

Designed for thrusting, the earliest Aegean swords were long with thin blades, the longest measuring 0.82 m (32.3 inches). To protect its wielder’s hand, some featured horned grips or separate attachments which eventually became part of the same casting as the blade and tang.

However, since bronze bends easily and longer swords often snapped near the hilt, short swords with stouter blades were favored with later types resembling dirks, daggers, and knives.

In her journal, archaelogist N.K. Sandars said, “Some of the shorter swords may have served as knives or double-purpose knife-daggers.” She also created the Sandars Typology, chronologically categorizing Bronze Age Aegean swords used from the 15th to 12th century from A to H.

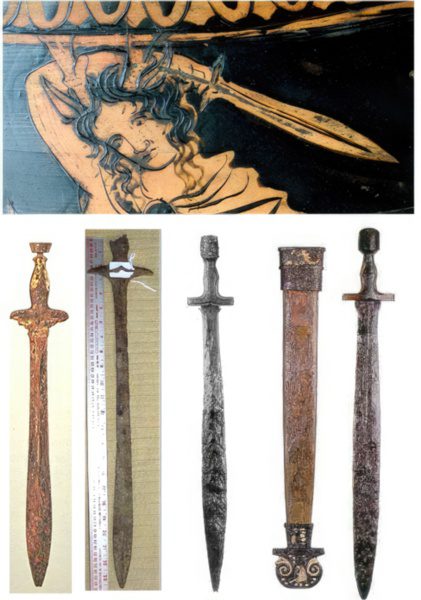

2. Naue II-Type Sword

During the late 13th century BCE, the Naue II-type sword—also known as the Griffzungenschwert or grip-tongue sword— was introduced to the Aegean from Central Europe and remained in use until the 6th century BCE.

The blade’s long, parallel-sided cutting edges measure between 19.7 to 27.6 inches (50 to 70 centimeters) and features a tang, allowing hilt pieces to be riveted in place. Greek versions often feature a distinctive half-moon-shaped pommel at the end of the hilt.

Archeologist Anthony Snodgrass, an expert on Archaic Greece, stated that the Naue II-type sword is regarded as the first true cut-and-thrust sword. It evolved from earlier thrusting weapons used in close combat, capable of cutting through leather armor and inflicting significant damage to bronze armor and helmets.

3. Xiphos

Although “xiphos” means “sword”, it became the name of the leaf-bladed sword of the hoplites, the citizen soldiers who formed the backbone of Greek infantry.

Its double-edged blade is narrow at the base and swells towards the tip. The hilt typically features a cylindrical pommel and crossguard, providing additional protection for one’s hand.

The xiphos served as the secondary weapon of both Classical and Hellenistic Greece. While hoplites primarily engaged their enemies with spears, xiphos were used in close-quarters combat.

Military historian Mike Loades pointed out that the leaf-shaped blade of the xiphos was designed with a weight-forward balance, making it effective at delivering strong hacking blows and thrusts.

4. Kopis or Machaira

The kopis or machaira featured a recurved blade—curved backward or inward. Some versions had a knuckle guard on the hilt to prevent it slipping from one’s hand. Military historian Mike Loades noted that the machaira was a cleverly designed cut-and-thrust sword, versatile enough to perform thrusts, chops, and drawing cuts.

Living just a generation before Alexander the Great, the Greek historian Xenophon’s experience led him to document his insights on horsemanship and cavalry warfare. He advocated using the machaira to deliver cutting blows from horseback.

5. Encheiridion

The Spartans favored the leaf-bladed xiphos but often relied on the shorter sword—the encheiridion, meaning little hand weapon. This stabbing weapon was well-suited to the Spartan’s close-quarters fighting, making it efficient in chaotic melee situations.

Historian Richard Taylor noted that Herodotus recorded various peoples in the Persian army armed with encheiridia, suggesting their use was widespread and possibly adopted from Persians. Nonetheless, the short sword was likely a universal weapon and should not be confused with the curved Spartan knife known as the xyele.