The History of Hamon in Japanese Swords

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

The hamon, a unique pattern found along the hardened edge of Japanese swords, sets these blades apart from other swords in the world. It was originally developed to make functional, effective, and durable weapons, but it also became an aesthetic element. For about five hundred years, Japanese swordsmiths transformed the basic hamon into the intricate and beautiful patterns we recognize today.

Let’s delve into the rich history and evolution of the hamon in Japanese swords.

Why Is the Hamon Essential in Japanese Swords?

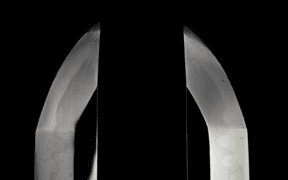

Hamon patterns can range from straight lines to arcs, zigzags, or other forms, with specific patterns often associated with particular schools or traditions of swordmaking.

Functionally, most hamon are the same, with their designs reflecting the swordsmith’s skill and artistry to complement the blade’s overall appearance. As long as the hamon is well-crafted, unbroken, and wide enough for re-polishing, any pattern can be equally effective for a good sword.

However, a “properly constructed” hamon can enhance a blade’s cutting ability and minimize edge chipping and damage, as briefly explained below.

(For a more comprehensive read, our article about Types of Hamon that covers the different types of hamon and characteristics.)

A Brief History of the Hamon

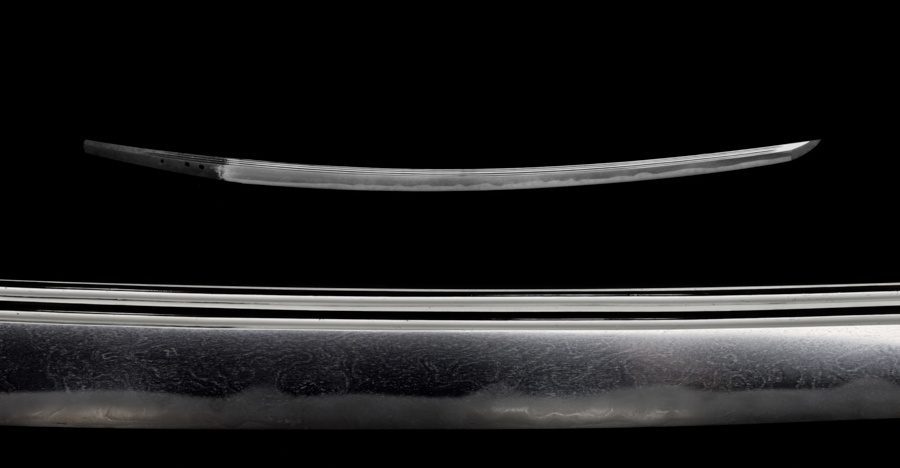

As Japanese swords evolved over the centuries, they became larger and developed a curvature, leading to wider and more complex hamon patterns. These changes in the hamon were designed to enhance the weapon’s functionality, effectiveness, and durability.

In the Pre-Heian Period (Before 794 CE)

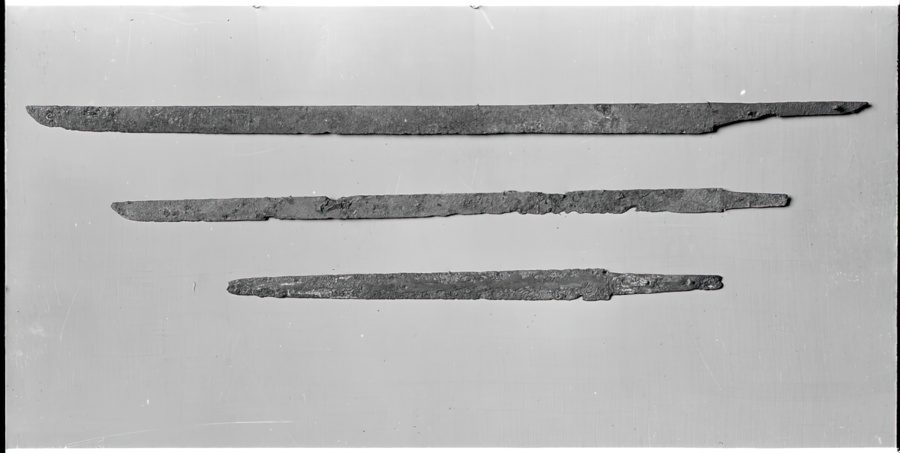

The early steel swords in Japan, called chokuto, are straight and thin and were made from at least the 4th or 5th century to the 10th or 11th century. These swords, along with the technology to work with steel and make them, are believed to have been imported from China through Korea.

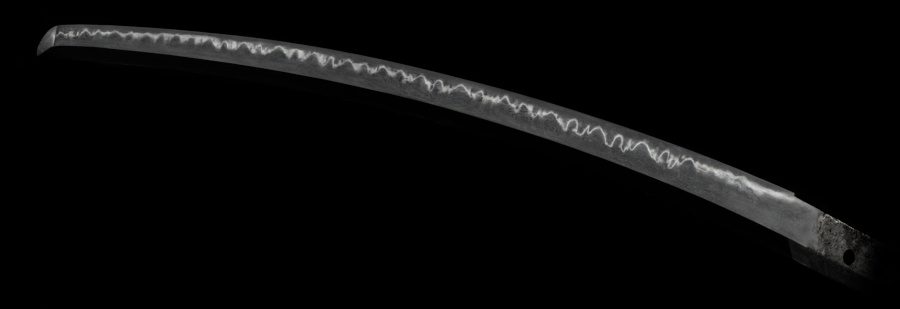

By the late Kofun period (mid-6th century to early 8th century), Japanese swordsmiths had begun refining their method of hardening swords. They started applying differential hardening techniques to enhance both the durability and the hardness of the edge, producing a visible pattern known as hamon. This resulted in the edge being hardened, more than that of the steel towards the back of the blade.

A sword owned by Prince Shotoku Taishi during the Asuka period (552–645) with a katakiriha-zukuri blade featured a narrow, straight hamon. Leon and Hiroko Kapp, experts in the craft of Japanese swords, noted that this type of hamon has several disadvantages:

- The cutting edge, made of hardened steel, is brittle and prone to chipping. A chip can extend past a narrow hamon, and polishing would require grinding away a significant portion of the blade to restore the straight edge.

- A chip might not extend beyond the hamon but could instead spread laterally across a broad section of the cutting edge.

In the Heian Period (794 – 1185 CE)

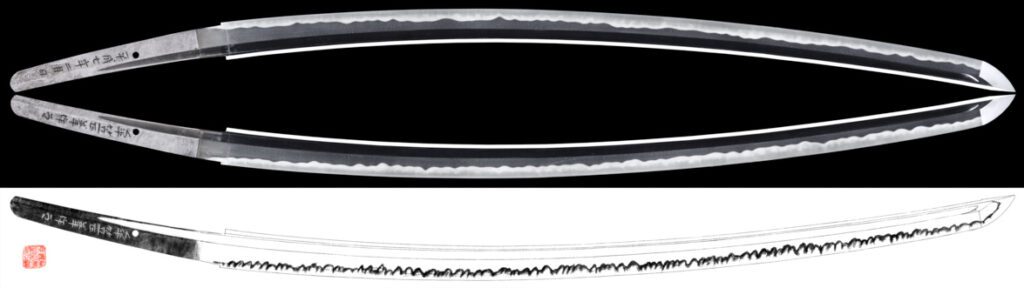

By the mid-Heian period, Japanese swords had evolved, with blades becoming longer, thicker, and more curved compared to those of earlier periods. Swordsmiths also learned to create wider hamon to reduce the risk of a chip extending through the hardened edge. They developed a new hamon shape called gunome, designed to prevent chips from spreading laterally.

A gunome hamon features a series of tooth-like projections, known as ashi, extending from the hamon’s border to the blade’s edge. When the sword is used, any chipping that occurs is limited in size by the distance between two ashi. By the end of the Heian period, wider and more complex hamon emerged. Among them is the choji hamon, which resembles cloves.

In the Kamakura Period (1192 – 1333 CE)

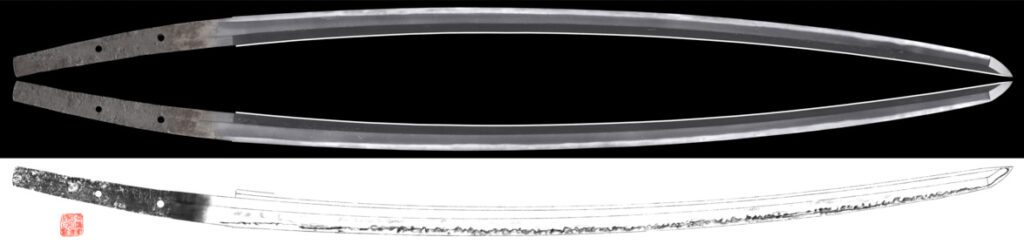

By the 12th century, the samurai class had gained significant power and influence, leading to a high demand for effective swords. Early Kamakura-period swords featured well-defined hamon, often with gunome or choji patterns.

By the end of the Kamakura period, the Gokaden school, comprising the five major swordmaking traditions, had developed in Japan. Each school produced effective swords with its own distinctive hamon. The Gokaden traditions remained influential throughout the early Muromachi period (1338 to 1573). In fact, newly-made Japanese swords are still modeled on those from the Kamakura period.

In the Edo Period (1603 – 1867 CE)

In 1868, the Meiji Restoration reinstated imperial authority and ended the Tokugawa shogunate. While the new Meiji government began to modernize the Japanese army and navy, military officers continued to carry swords known as gunto.

Although traditionally-made blades were still produced during this period, the Japanese began mass-producing swords to meet the high demand of the military. Forging shortcuts were employed, with the hamon created by tempering the blade in oil instead of water. This method resulted in swords lacking the traditional characteristics of Japanese blades.

During wartime, antique swords from earlier periods were remounted for military use. Markus Sesko, an expert in Japanese arms and armor, noted that the term gunto does not indicate whether a blade is traditionally made or not.

In the Modern Era (1912 – Present)

Japanese swordsmiths continue to forge swords using traditional materials and methods. Despite having access to advanced technology and metallurgy, they must still adhere to the rigorous standards of traditional Japanese swordmaking. Today, Japanese swords are primarily regarded as works of art, with the hamon being one of the most aesthetically significant features of the blade.