Learning the History of Seppuku: A Samurai’s Philosophy of Ritual Suicide

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Seppuku, also known as hara-kiri, is one of the most striking and symbolic practices in Japanese history. Far from being just a grim ritual, it was seen as an honorable way to confront shame or defeat—a final act of courage and control.

This tradition emerged in medieval Japan and carried on into modern times, particularly among warriors and their families. For them, it wasn’t just about death—it was about reclaiming dignity when all else seemed lost.

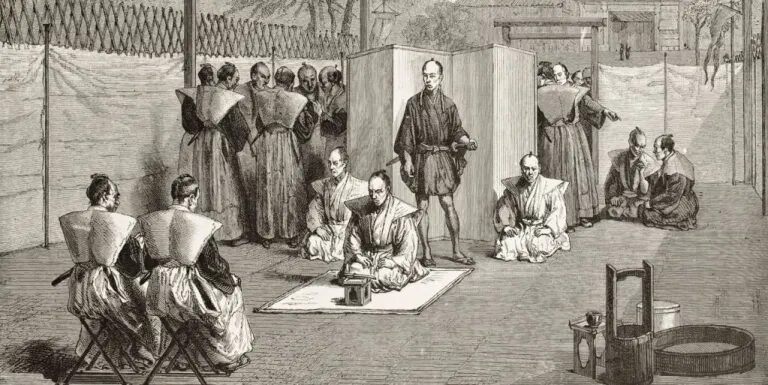

By the Edo period (1600–1867), the act of seppuku had evolved into a highly detailed ritual. It began with the use of a short sword to cut open one’s stomach, a deliberate and symbolic gesture that gave hara-kiri its name, meaning “belly-cutting.”

Yet this harrowing act didn’t end there. A trusted second, often a close friend or ally, would step in to deliver a swift and merciful beheading—bringing the ritual to its somber conclusion. Together, these elements formed a ceremony that spoke volumes about honor, loyalty, and the weight of personal sacrifice.

The Early History of Seppuku

Hara-kiri, also known as belly-slashing, first appeared in a Japanese story from 713. It tells about a goddess named Aomi who, upset over losing her husband, cut her stomach and drowned herself.

This story suggests that the idea of cutting one’s stomach as a form of suicide started around the 6th or 7th century, long before it was officially recorded.

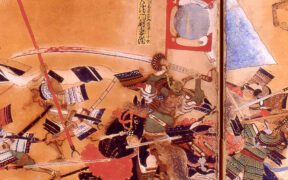

By the 12th century, hara-kiri became linked with samurai warriors.

For example, in 1170, a samurai named Minamoto no Tametomo killed himself after his rebellion failed. Before dying, he shot an arrow that sank a ship full of enemies and then cut open his belly. This act was seen as heroic and reflected the fierce nature of early samurai.

Early samurai viewed hara-kiri as a way to express rage or regain honor, often choosing to suffer through the pain rather than being killed quickly by an enemy.

They would make a cross-shaped cut in their belly. This practice shows how hara-kiri evolved from a desperate act of fury to a more formal way of restoring honor among samurai.

Seppuku During the 1500s: The Development of Honorable Death

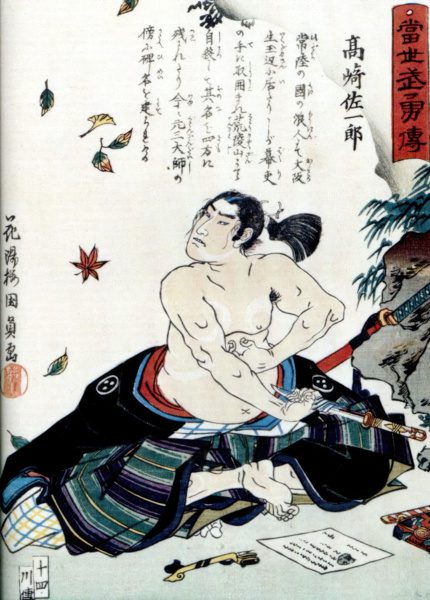

In the 1500s, the practice of seppuku, or ritual suicide, became a formal part of the samurai code, known as bushido.

This code valued honor above all, and seppuku was seen as a way to die with dignity rather than face dishonor. Interestingly, losing one’s samurai status was considered worse than seppuku, highlighting the importance of honor to samurai.

One famous example from 1582 is Nishina Morinobu, who chose seppuku after a brave last stand, similar to the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae. He and his few remaining warriors fought fiercely before taking their own lives, earning respect even from their enemies.

By the late 1500s, ‘kaishaku‘ became a term linked with seppuku, referring to the act of mercy killing by beheading to spare the individual from the agony of seppuku.

The person performing this task, a ‘kaishakunin‘, was a skilled swordsman and often a close associate, showing a deep bond and loyalty. This act was so sacred that the kaishakunin also had to commit seppuku, proving their devotion.

All these developments resulted in a nearly fully formed ritual of seppuku by the dawn of the Edo period, with all its associations of martial honor and poetic beauty.

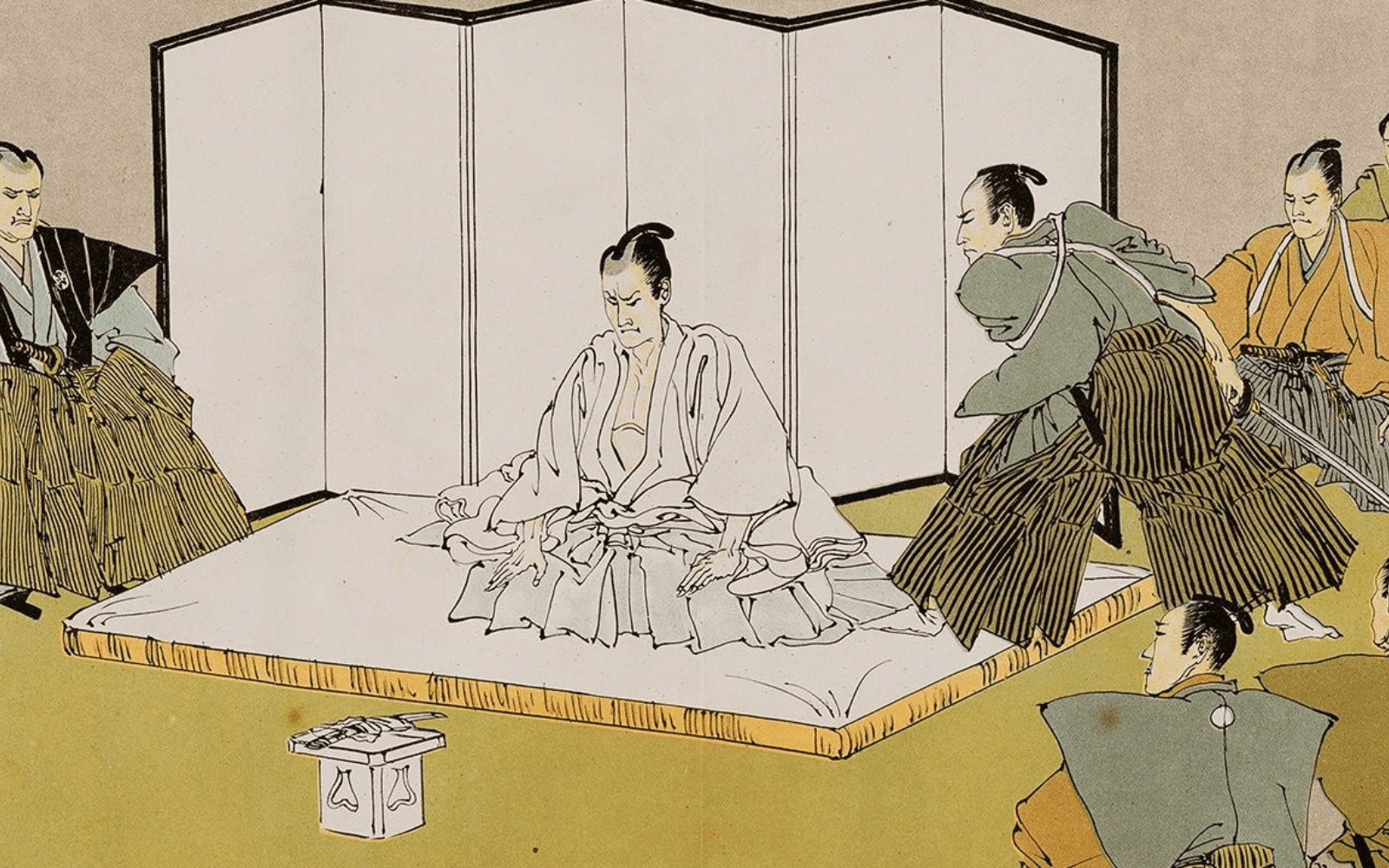

The Formalised Ritual of Seppuku

Starting in the 1500s, the practice of Seppuku became very formal. It involved detailed steps and rules.

The place was set up based on the samurai’s status, with mats and curtains arranged. Candles and incense were used to make the situation less upsetting for those watching.

A special kimono was worn, and either a knife (tanto) or a short sword (wakizashi) was used for the act. It was not allowed for the kaishakunin to use his own sword for this purpose.

They decided in advance the exact moment for the kaishakunin to act. This could be as soon as the samurai started to cut himself or when he reached for his blade, sometimes ending his life before he could complete the act.

This highlights how structured Seppuku had become. There were also different kinds of Seppuku, each with its own name.

Types of Seppuku

| Ichimonji | A single horizontal cut across the belly |

| Jūmonji | A horizontal cut across the belly followed by a vertical cut in the shape of a cross |

| Hachimonji | Two vertical cuts across the belly |

| Sanmonji | Three horizontal cuts across the belly |

| Tachi-Bara | A stomach cut performed in a standing position |

| Oi-Bara | Suicide immediately after acting as kaishakunin for one’s lord or daimyo |

| Kanshi | Suicide committed in protest of another’s actions |

| Kage-Bara | A cut across the belly, which is then concealed and then revealed to others with dramatic effect, usually as a form of Kanshi or to prove a point |

Seppuku During the Edo period

In the peaceful Edo period, samurais had fewer chances to die honorably in battle or through seppuku. Yet, they still committed seppuku for honor, especially after their lord’s death, a practice called ‘junshi‘.

Seppuku was also a punishment for samurais who broke the law, like murder, theft, or fighting, to maintain their families’ honor.

Using seppuku for such offenses helped demilitarize society. Even drawing a sword in the palace was a severe disrespect, leading to forced seppuku, reflecting the shift from military to civil honor.

By the end of the Edo period, the 1877 Satsuma rebellion, led by Saigō Takamori, saw samurais fighting to restore their status against modern reforms.

Despite their defeat, Saigō and his men chose seppuku over capture, valuing samurai dignity.

Though Saigō might have died from a bullet, his followers beheaded him posthumously to preserve his honor, highlighting their enduring commitment to samurai values of honor and noble death.

Seppuku in Modern Japan

Seppuku, a traditional Japanese ritual, has persisted into modern times. Notably, after Emperor Meiji died in 1912, General Nogi Maresuke and his wife Shizuko performed seppuku as an act of loyalty (junshi).

During World War II, Japanese kamikaze pilots carried on seppuku traditions, including writing death poems and seeking an honorable death. After Japan’s defeat in 1945, many military officers also chose seppuku.

A famous recent case was Yukio Mishima, a writer and nationalist who, in 1970, tried to overthrow the Japanese government to restore samurai values. When his coup failed, Mishima and some followers committed seppuku, showing their dedication to his cause.

Seppuku has evolved from a defiant act to a ritual of honor, reflecting Japan’s enduring values of honor and tradition up to today.