Nodachi vs Katana: Characteristics, History, and Combat

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

The nodachi and katana are edged weapons of war from Japan used by the legendary samurai. Both are melee weapons with unique attributes.

This article will discuss their characteristics, explain how each was forged, and examine their combat effectiveness. We will conclude with what we believe to be the victor in a duel.

Characteristic Differences

Both the katana and nodachi are daito, Japanese long swords with over two shaku (23.6 inches / 60 cm) in length. While the nodachi can be referred to as a katana (sword), it is a completely different type of weapon. The nodachi is also sometimes called odachi (field sword) but the term difference between them is not clearly defined.

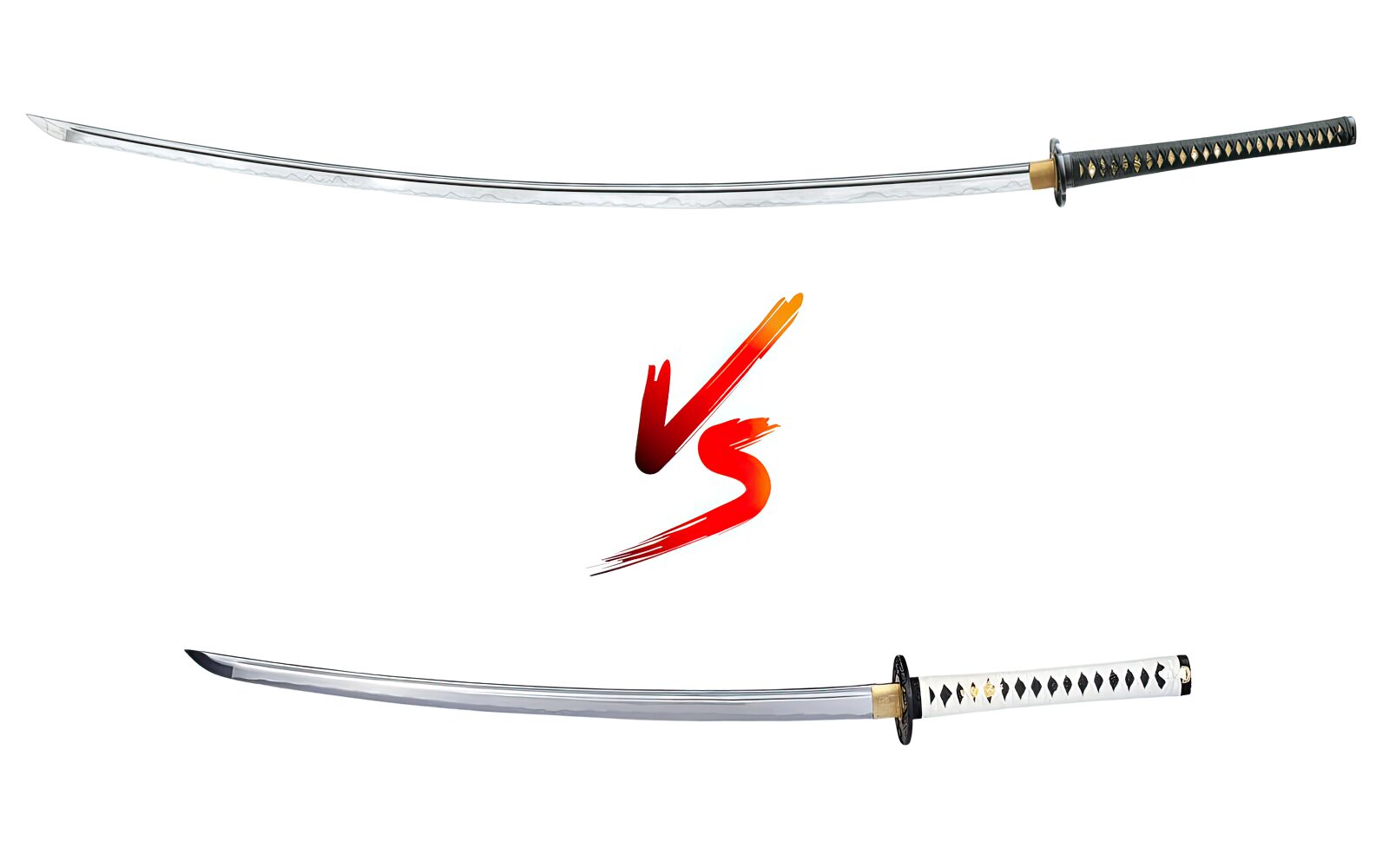

Blade

Both swords are made with high-carbon, traditional, high-quality Japanese tamahagane steel.

They also share a curved blade with a single edge, ranging in different zukuri (blade profiles) with unique kissaki (blade tips). Both feature bohi (grooves) for lowering weight and modifying balance.

The nodachi had a longer blade, around 45 inches (114 cm), while the shorter katana blade reached about 29 inches (74 cm).

Hilt

Both of these Japanese blades have a tsuka (hilt) handle with a tsuba (guard) for protection and a wooden core wrapped with samegawa (ray skin) under a tight tsuka–maki (cord wrap).

For added security, the nodachi usually features two sets of mekugi (bamboo or wooden pegs), while the katana varies between one or two. The nodachi’s hilt is around 17.5 inches (45 cm), while the katana’s is 10 inches (25 cm).

Scabbard

Both swords’ saya (scabbard) are made from wood, the nodachi’s being larger.

The wielder can carry the nodachi on his back, an action called seoidachi. It can also be unsheathed by a private retainer, while the katana is traditionally carried on the left side with the edge facing upward.

The katana was combined with a daisho set that comprised a wakizashi short sword or a tanto dagger.

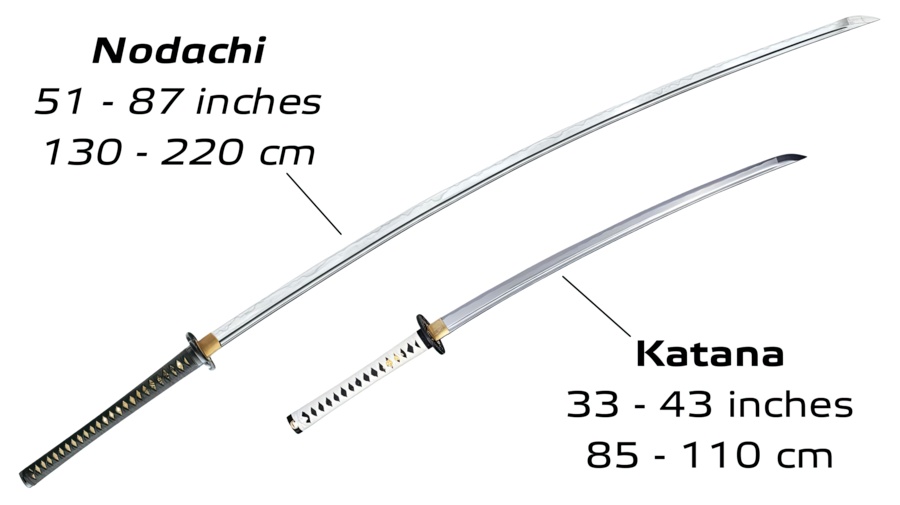

Size and Weight

The nodachi was the largest sword in feudal Japan, extending from 51 to 87 inches (130 to 220 cm) and weighing roughly 5 lbs (2 kg).

The katana, the most versatile secondary weapon, was around 39 inches (99 cm) with a lighter weight of 2.42 lbs (1.1 kg).

Historical Significance

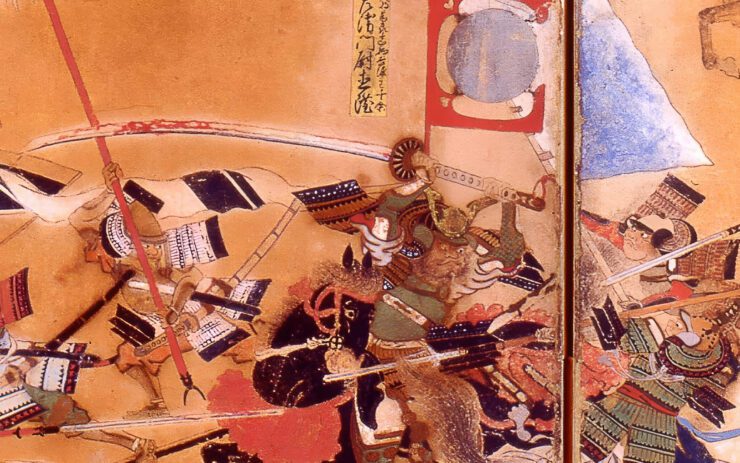

The two-handed nodachi, due to its size and heft, was valued for its impact behind each strike and nicknamed the “battlefield sword.” Beginning in the 13th century, it was used as a situational weapon, evolving from the previous tachi.

The Japanese katana was founded during the Muromachi Period (14th – 16th century) after the uchigatana, which was carried point up. It was mainly a sidearm, effectively used as a primary weapon. It was integral to Japan, its battlefields, Japanese kenjutsu (sword martial arts), and the highly respected seppuku ceremony.

The katana’s reputation rocketed during the peaceful Edo Period (17th – 19th century), while the nodachi served as a status symbol of advanced swordsmanship and a challenging training tool, enhancing katana skills.

Nodachi and Katana in Battle (Combat Preference)

The nodachi proved deadly in capable hands and was especially useful for breaking up tight, compact battle lines when attacking from flanks, while on horseback, and for taking down enemy cavalry. Its extra mass, size, and relatively slim blade made it the ideal slicing weapon.

While the nodachi excelled in specific combat styles, the shorter katana achieved the same while performing admirably in various other combat situations. It was a weapon carried by foot soldiers or highly trained samurai.

The nodachi was a primary weapon and could be used with one hand, but it was meant for two-handed slashing and was extremely effective against unarmored opponents.

It wasn’t adequate for combatting armor and was eventually replaced by the equally large naginata, yari spear, kanabo mace, and teppo bullets in the last decades of the Sengoku Jidai Era (15th and 16th century). However, with its high level of versatility, the katana was irreplaceable.