Tanto Explained: Characteristics, History and Facts

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

A traditional Japanese dagger, the tanto usually had all the fittings of a samurai

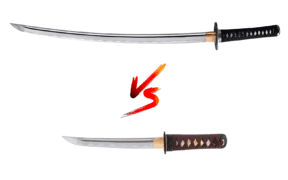

This article discusses the history of the samurai tanto, its unique characteristics, and why it is comparable to other samurai swords.

How Long is a Tanto Dagger?

Today, the Japanese Firearms and Sword Law defines a tanto as any blade that is under about 11.8 inches (30 centimeters) in length. However, prior to this law, several blades longer than 11.8 inches were categorized as tanto, especially the sunnobi tanto—a large dagger with a blade length of about 13 inches (33 centimeters).

Characteristics of the Japanese Tanto

Despite the size of the tanto dagger, it usually has the same craftsmanship as its larger counterparts. Therefore, many collectors consider it a work of art comparable to samurai swords like wakizashi and katana. Here are the unique characteristics of this Japanese dagger:

Metal and Construction

Japanese swordsmiths craft tanto blades from tamahagane, a specific carbon steel used in samurai swords. Although most tanto replicas have high carbon steel blades, they are not of tamahagane steel. Modern tanto replicas also feature damascus steel, recognized by its watered, streaked appearance due to varying carbon levels.

Blade Appearance

The traditional Japanese blades are often not reflective and darker than modern steel. Like most samurai blades, tanto blades tend to be whitish on the edges and grayish on the opposite side. However, they vary in shape, groove, and carvings, though they often have the hamon (temperline patterns) and jihada (grain patterns).

Blade Shape

While the tanto blade is often slightly curved like katana blades, it is sometimes straight or even broad and stubby. The so-called moroha is double-edged and has a diamond-shaped cross-section. Some have a chisel-type edge or tip, while others are similar to modern knife blades, hence it is also sometimes referred to as a tanto knife.

Temperline Pattern (Hamon)

Like katana swords, tanto daggers have clay tempered blades that feature a genuine hamon (temperline pattern), indicating the boundary between the hard and softer steel. The hamon is usually an irregular series of pointed and rounded waves. However, the so-called tourist tanto replicas often feature an etched hamon.

Grain Pattern (Jihada)

The jihada is the resulting pattern from repeatedly folding the steel while forging. Depending on how a swordsmith folds and forges the steel, the grain patterns may have a combination of straight grain (masame hada), wood grain (itame hada), and circular motifs.

Grooves (Hi)

The grooves lighten the blade without compromising its structure. Many tanto daggers have straight or parallel grooves that usually extend the full length of the blade. Some have shaped groove ends, added for decoration.

Carvings (Horimono)

Some tanto blades have decorative carvings (horimono) on both sides, especially ones crafted by famous Japanese swordsmiths. Some depict a carving of a Buddhist deity and symbolic creatures like a dragon, tiger, or other motifs. Some traditional images like straight swords, Sanskrit, and kanji characters are also not uncommon. Swordsmiths make their own grooves, but craftsmen are the ones who specialize in making elaborate horimono.

Signature on Tang (Mei)

The tanto usually has a full-tang blade, though some tang tapers toward the bottom. Like most Japanese swords, the dagger has an inscription on the tang, often the mei or swordsmith’s signature but may also include other information.

Swordsmith inscribes the mei with a chisel and a hammer. Still, the signature can be unique, as one can use a thin or thick chisel to carve calligraphy. Sometimes, the owner of a new tanto will ask to include an owner’s mei and other information about his family.

Tanto Mounting

Sometimes, the tanto dagger comes in a plain scabbard (saya) called shirasaya, though decorative mountings like aikuchi and hamidashi are more common.

Aikuchi

Translated as a fitting mouth, the aikuchi mounting refers to a dagger without a guard. The handle and the tanto scabbard meet without the tsuba (guard). Still, it is a form of koshirae (decorative mounting) with lacquered scabbard and hilt. Some decorative themes include phoenix, vines, and mother-of-pearl inlay designs.

Hamidashi

The hamidashi is a tanto mounting with a small tsuba or guard, slightly larger than the grip. Sometimes, it includes slim kozuka knives stored in the sheath pocket next to the dagger, so the tsuba also has hole openings for the knives. Technically the term kozuka refers to the knife handle while the blade is the kogatana. It served as a utility knife for opening letters, trimming loose hair, and so on.

Facts About the Japanese Tanto

The tanto is a Japanese term used for blades of less than 30 centimeters in length, so it is often called a dagger. Here are the things you need to know about the traditional Japanese dagger:

Japanese blades are categorized according to their length.

In Japanese measurement, 1 shaku is equal to 30.3 centimeters. The blade length starts from the tip to the notch at the top of the tang (munemachi). As a rule of thumb, Japanese blades less than 1 shaku are tanto, while ones from 1 to 2 shaku are short swords or shoto, mostly wakizashi. On the other hand, swords over 2 shaku are the long swords or daito, usually katana and tachi. However, a tachi shorter than 2 shaku is regarded as a kodachi.

Large tanto daggers were sometimes called sunnobi.

Before the Japanese Firearms and

The samurai carried the tanto on his belt.

The tanto served as a companion sidearm to the samurai. Some believe that samurai wore a tanto only when armored and opted for a wakizashi in everyday dress. However, a famous hanging scroll depicting Honda Tadakatsu portrays him wearing two companion swords—the wakizashi and the tanto. Experts suggest that there were no strict rules on how many weapons a samurai should carry.

The samurai used the tanto for seppuku ritual suicide.

To avoid capture after war defeats, the samurai performed seppuku ritual suicide, believed to give them an honorable death. They used the wakizashi but later preferred the tanto for the purpose. The dagger often had a hilt and scabbard of plain white wood suited for the ritual.

Members of other social classes also carried tanto for self-defense.

Many believe that the ninjas used the tanto, apart from their ninjato

Japanese swordsmiths could produce three tanto daggers each month.

In modern Japan, the government allows licensed swordsmiths to make high-quality traditional types of swords from tamahagane. In order to maintain the craftsmanship of swords, each swordsmith could craft three shorter blades—tanto or wakizashi—or two long swords per month. Also, owning a tanto or any blade longer than 15 centimeters requires certification and permit, but only for home ownership. The only legal weapons to carry around in Japan are blades shorter than 6 centimeters.

Tourist tanto daggers are of no interest to Nihonto collectors.

In the 19th century, tanto daggers served as tourist souvenirs. Most featured carved and painted figures like dragons, fish, Japanese peasants, and others. While carved designs made them an art piece, these tourist daggers often lacked clay tempered blades, which are valuable to Japanese

Tanto daggers in fan-style mounts also served as tourist souvenirs.

Some tourist daggers had mountings simulating a folded Japanese fan. These tanto daggers usually had poor quality blades. They were popular in the late 19th and 20th centuries among tourists and to those who wanted to bring concealed weapons.

The tanto jutsu martial arts involve fighting with the tanto.

Even though the tanto jutsu (art of the dagger) is not widely practiced, the tanto is significant in kata demonstrations and competitions. However, practitioners use a wooden tanto for training, allowing them to learn the concepts of attacking and defending without the risk of injury.

History of the Japanese Tanto

The tanto emerged during the Heian period between 794 and 1185 as a practical weapon. Eventually, it evolved into a decorative weapon carried by samurai and members of other social classes.

In the Kamakura Period

From 1192 to 1333, several

In the Nanbokucho and Muromachi Periods

During the Nanbokucho period, the samurai used extremely long swords known as nodachi or odachi, ranging between 90 and 130 centimeters long. No wonder tanto also reached lengths more than 30 centimeters, often referred to as sunnobi tanto. Hence, the line between a long dagger and a short

These large daggers reflected the martial spirit of the period when battles dictated the changes in

In the Momoyama Period

The Momoyama period is considered the age of political unification in Japan, as the daimyo Oda Nobunaga unified almost all provinces under a central government. Swordsmiths began to craft several artistic blades, including tanto with carvings or horimono. In the earlier periods, the samurai wore the tanto with tachi, but during this period, the wakizashi replaced the dagger as the shorter

In the Edo Period

Under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan had a period of peace, political stability, and economic growth. As a result, swordsmiths produced flamboyant hamon or temperline patterns which were evidently seen on

In the Meiji Period

In 1876, the Meiji government prohibited the wearing of swords, so many tanto daggers became ceremonial weapons. The tanto production continued but primarily for the imperial court and state ceremonies, not for public use. When Japan opened to the West, tanto daggers eventually served as souvenirs to Europeans, so Japanese craftsmen created several elaborate mountings for the export market.