Types of Japanese Sword Tang (Mei) Signatures

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

The signatures and inscriptions found on the tangs of Japanese swords, known as mei, are a hallmark of craftsmanship and tradition.

Typically engraved using a chisel and hammer, these signatures often bear the swordsmith’s name and may also include details like the town or province of origin.

Mei styles can vary significantly between swordsmiths, appearing in either block-like printed forms or flowing cursive scripts.

Their placement also differs depending on the type of sword, with variations commonly seen between tachi and katana.

But what do these differences tell us? From identifying the swordsmith to uncovering the blade’s history, the types of mei and their characteristics hold the key to understanding the story behind each sword.

Examining the Mei and the Tang in Sword Appraisal

The tang of a Japanese sword (nakago) contains various information about the blade, particularly the mei (signature). However, only blades that fully meet the standards are signed. The mei can consist only of the swordsmith’s name or may include additional details such as the:

- Smith’s title

- Smith’s location

- Date the blade was made

- Name of the blade’s owner

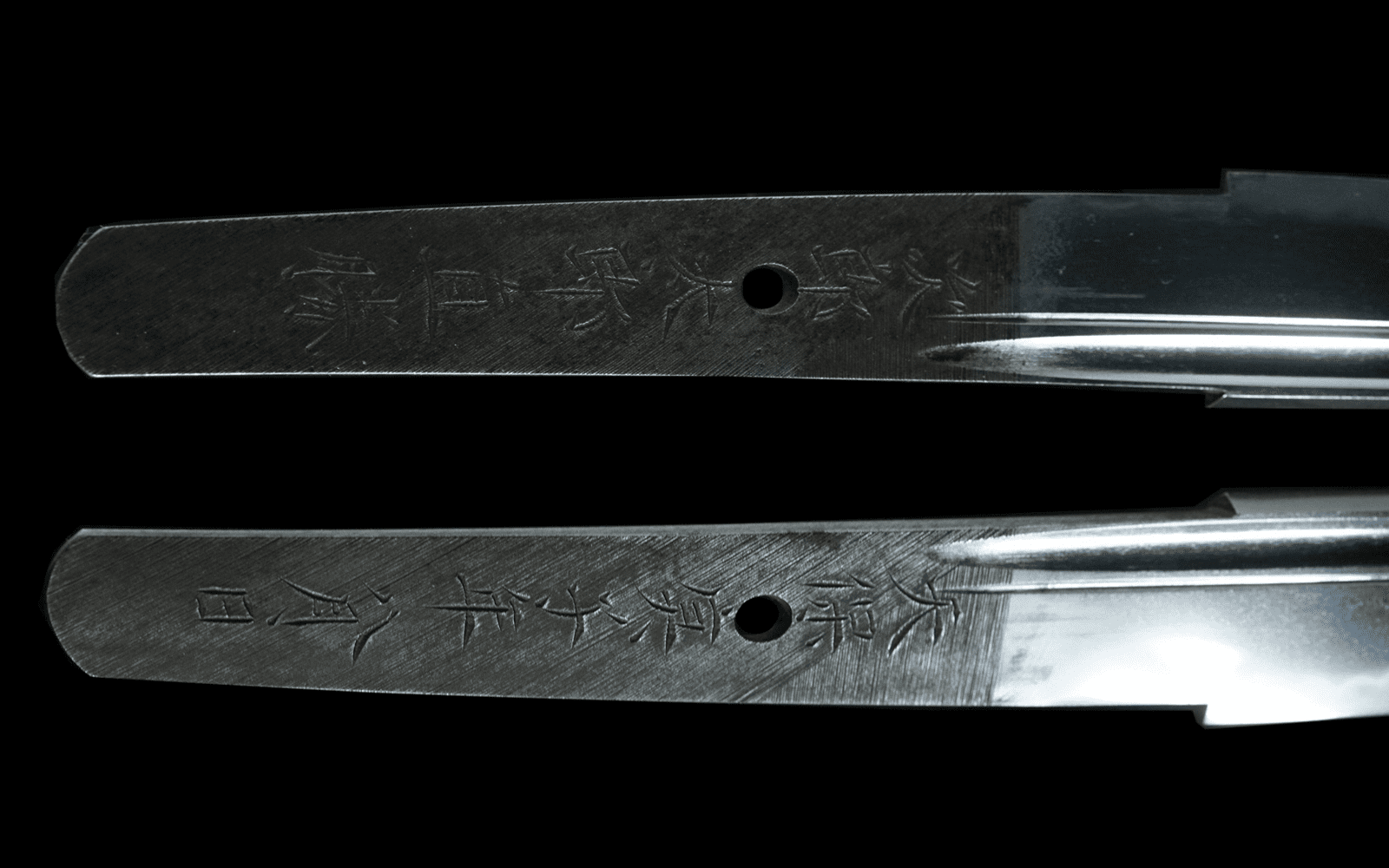

Inscribed using a chisel and a hammer, the signature hints at the characteristics of a swordsmith. This includes factors such as the:

- Type of chisel used (e.g., thick or fine chisel)

- Type of hammer employed (light or heavy) based on the strokes on the metal

- Additional distinguishing features like the depth and number of chisel strokes per inch.

Signature styles are unique and vary just as much as different handwritings. The inscribed characters may be cursive scripts or block-like printed styles. Unfortunately, forgeries are common. Therefore, a blade should never be judged solely based on its mei in Japanese sword appraisal.

When examining a sword’s tang, there are several factors to look for:

- Since the tang of a Japanese sword is never cleaned or polished, the rust that builds up on the tang over time becomes an important indicator of the sword’s age.

- The color of the rust, clarity of remaining mei, and yasurime (file marks) help to date the sword and determine its authenticity.

Therefore, cleaning the tang of an old Japanese blade can diminish much of its value.

The Various Types of Mei on Sword Tangs

The mei (銘) is chiseled into the tang. Blades that still have their original mei are known as zamei. Those without signatures are called mumei, likely due to absence of signing or the mei being lost when the blade was shortened. Meanwhile, gimei are blades with a false signature.

Here are the different types of mei found on Japanese swords and daggers:

1. Tachi-Mei

A tachi-mei (太刀銘) refers to a signature inscribed on the obverse of the tang (haki-omote side)—the side that face outwards when the tachi is worn suspended from the belt with its cutting edge facing down. Swords from the early Muromachi period, except for wakizashi and tanto, often featured tachi-mei.

2. Katana-Mei

A katana-mei (刀銘) is a signature of a sword carved on the sashi-omote side—the side that face outwards when the sword was worn thrust through the belt with its cutting edge facing up. The katana, wakizashi, and tanto often had a katana-mei. Therefore, it is the opposite of a tachi-mei. Most swords produced after the Muromachi period often had a katana-mei.

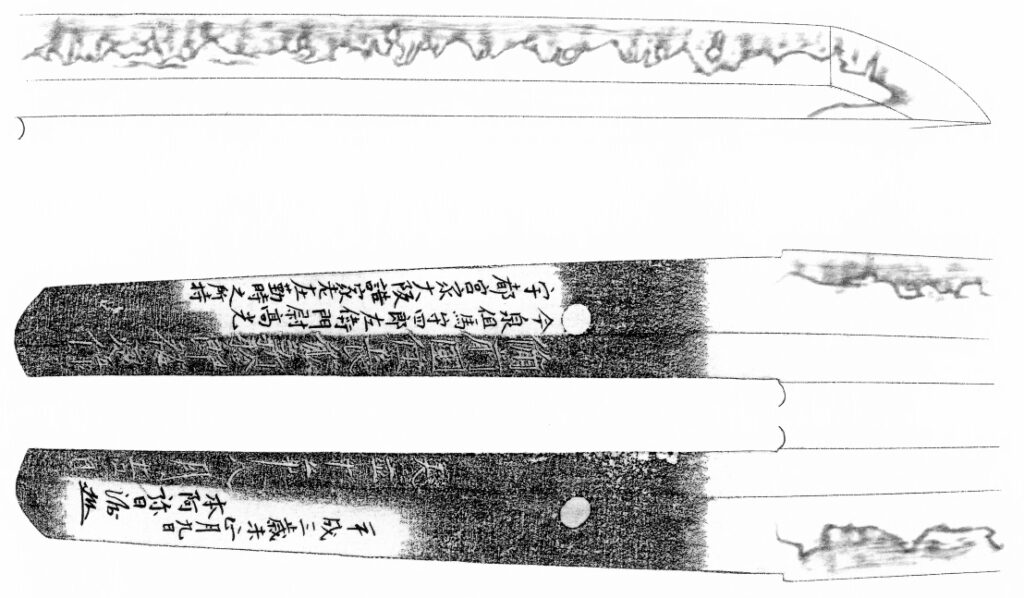

On the right side with gold lacquer: Kanbun 6th year, 5th month, 4th day” (寛文六年五月四曰), translated as (May 4, 1666.). With name of a famous sword tester, Yamano Kaemon no Jô Nagahisa (山野加右衛門尉永久). With inscription: Futatsu do setsudan (貳ッ胴截断), translated as “Cut through two torsos with one stroke.”]

3. Omote-Mei and Ura-Mei

Omote (表) is a generic term for outside, exterior, or front side. An omote-mei refers to the signature on the front side of the blade, typically featuring the swordsmith’s signature. Blades forged after the Muromachi period usually included the swordsmith’s title and address.

Depending on how the sword is worn, it can be differentiated between:

- Haki-omote – refers to the outside of the blade when the sword is worn tachi-style (suspended from the belt with its cutting edge down)

- Sashi-omote – refers to the outside of the blade when the sword is worn katana-style (thrust through the belt with its cutting edge facing up)

Ura (裏) is a generic term for inside or reverse side. An ura-mei refers to the inscription on the back side of the blade, usually featuring the date of manufacture and the blade owner’s name.

Depending on how the sword is worn, it can be differentiated between:

- Haki-ura – refers to the inside of the blade when the sword is worn tachi-style (suspended from belt with cutting edge down)

- Sashi-ura – refers to the inside of a blade when the sword is worn katana-style (thrust through the belt with cutting edge facing up)

4. Niji-Mei

The term niji-mei (二字銘) or “two-character signature” is a short signature with two Chinese characters, mentioning just the name of the swordsmith. Niji-mei were often seen on Koto swords, especially during the Heian and Kamakura periods. It was used by swordsmiths Muramasa, Masamune, Masatsune, Nagamitsu, and others.

5. Naga-Mei

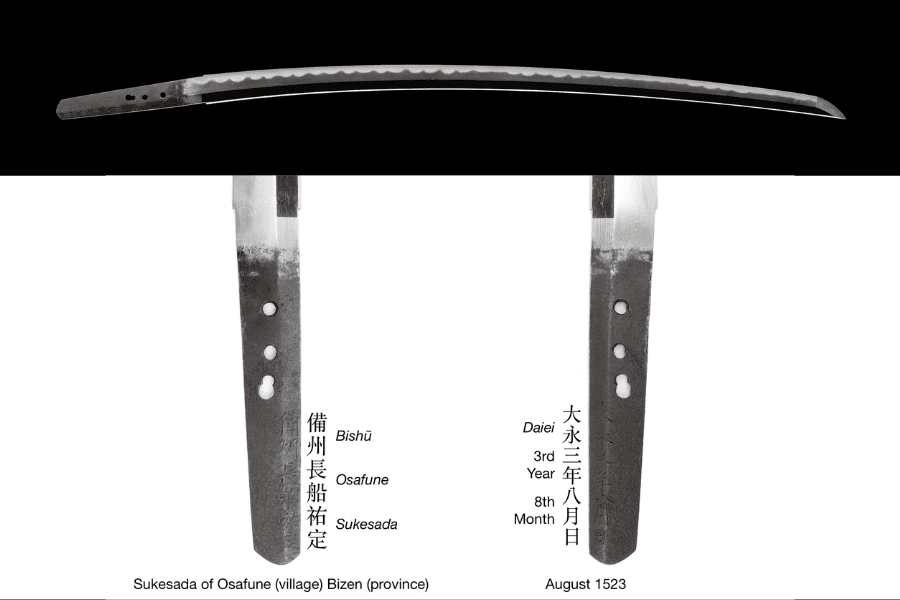

The term naga-mei (長銘) means long signature. This type of mei usually consists of six or more characters, usually including the swordsmith’s title, middle name, and address.

However, there is no rule specifying differentiation at six characters. Terms such as rokuji-mei, shichiji-mei, or hachiji-mei also refer to signatures with exactly six, seven, or eight characters, respectively. The nagamei became the standard after the Shinto era.

6. Zuryo-Mei

Some swordsmiths received their titles from the imperial court, such as suke (Third Lord or Second Assistant Lord), daijo (Second or Assistant Lord), kami (Lord). A zuryo-mei refers to a signature that includes such titles and frequently appears on Shinto and later swords.

7. Kaki-Kudashi-Mei

A kaki-kudashi-mei (書下し銘) refers to a signature in which the entire inscription is carved in one line on one side of the tang. It usually includes the swordsmith’s name, place of residence, and date of manufacture. Sometimes, a small space between the smith’s name and date is present.

The kaki-kudashi-mei was first used by Yamashiro and Bizen swordsmiths. The Yamato smiths also signed their blades (usually tanto and ken) on just one side throughout the Kamakura and Nanbokucho periods. Additionally, the Aoe swordsmiths used this type of signature mainly in the Nanbokucho period.

8. Tameshi-Mei

A tameshi-mei (試し銘) is an inscription on the tang commemorating a cutting test (tameshigiri). It often includes the name of the sword tester and notes the blade’s sharpness demonstrated during tameshigiri. It sometimes includes the statement that a target or body was completely cut through.

A tameshi-mei is often chiseled (kiritsuke-mei) or inlaid in gold (kinzogan) on the opposite side of the swordsmith’s signature. The practice of recording cutting test results on sword tangs was standardized during the Shoho (1644-1648) and Joo (1652-1655) eras.

9. Kiritsuke-Mei

The term kiritsuke-mei (切り付け銘) means added signature. It is inscribed later on the tang, probably after the blade has left the swordsmith’s forge. It also replaces the original signature when the tang is greatly shortened (o-suriage).

A kiritsuke-mei may include the blade’s history, sword’s owners, its nickname, and cutting test results. It can also contain information about the original signature if it had been greatly shortened and the name of the person who shortened the tang.

10. Damei

A damei refers to a substitute signature when a swordsmith’s mei is inscribed on the blade by one’s son or student with permission. It is regarded as an equivalent of the real signature. For instance, the Rai smiths or Rai-ichimon lack signed works, but they served as assistants to their masters Kunitoshi and others. Thus, it is likely that several Kunimitsu and Kunitoshi blades are damei by these Rai smiths.

11. Shu-Mei

A shu-mei (朱銘) refers to the red lacquer inscription of an appraiser. It was primarily done by members of the Hon’ami family, the official sword appraisers of the shogunate. An appraiser may provide the name of an attributed swordsmith on an unaltered tang or shortened tang without signature. Other information may include the blade’s nickname and cutting test result. Generally, a red lacquer was used to avoid carving directly onto the tang.

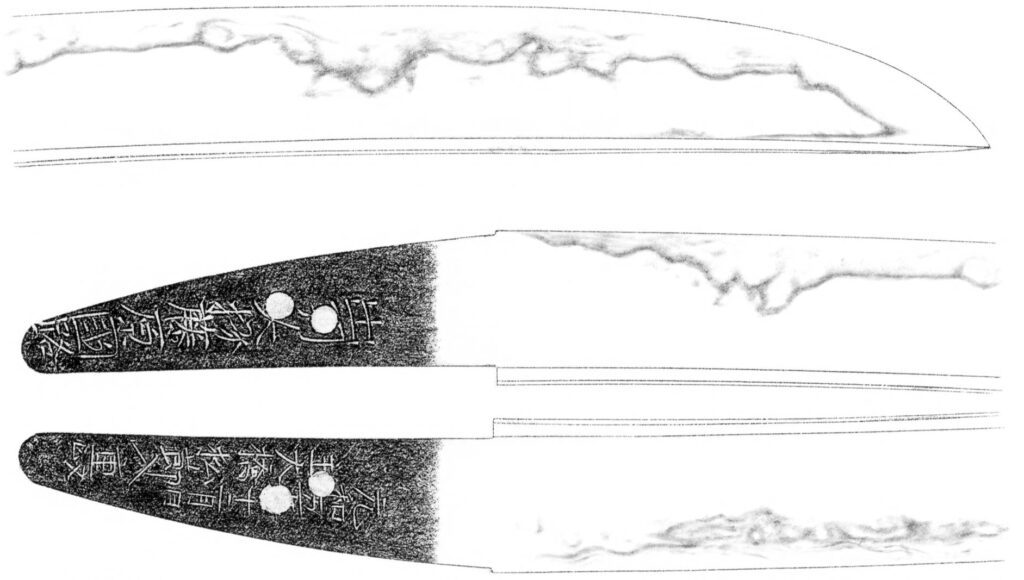

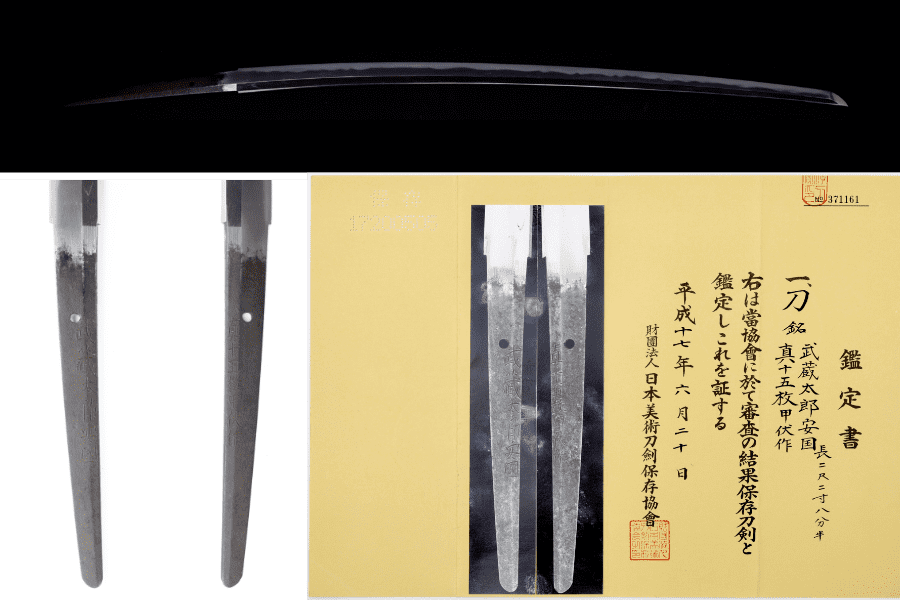

12. Kinzogan-Mei

A kinzōgan-mei (金象嵌銘) refers to a gold inlay inscription, usually made by members of the Hon’ami family. Their kinzōgan-mei usually featured the characters “Hon’ a” (本阿) for “Hon’ami” and the personal seal (kaō) of the appraiser. It also often included the name of the attributed swordsmith, owner’s name, blade’s nickname, and cutting test result.

13. Chumon-Mei or Tame-Mei

Both chumon-mei (注文銘) and tame-mei (為銘) refer to an inscription that bears the name of the person who ordered the sword. The terms chumon and tame are translated as order and for, respectively. The blade may also be described as chūmon-uchi (注文打), meaning custom made or special order sword. However, the term chūmon-uchi was coined to differentiate custom-made Sue-koto blades from mass produced ones.

14. Kinmei or Taimei

Both kinmei and taimei denote that a high-ranking individual such as an aristocrat, shogun, member of the Imperial family, or the emperor ordered the sword. These blades are known as kinmei-uchi (鈞命打) or taimei-uchi (台命打).

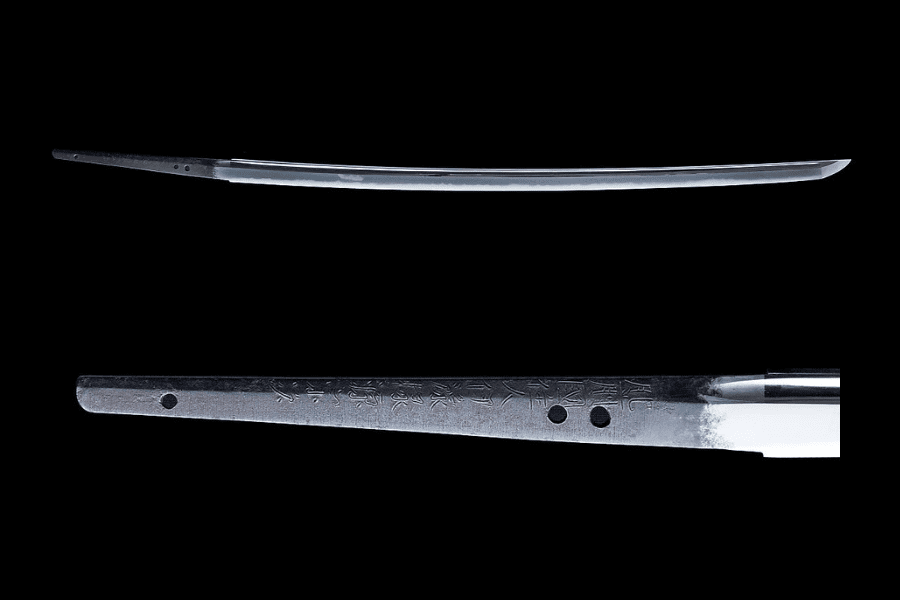

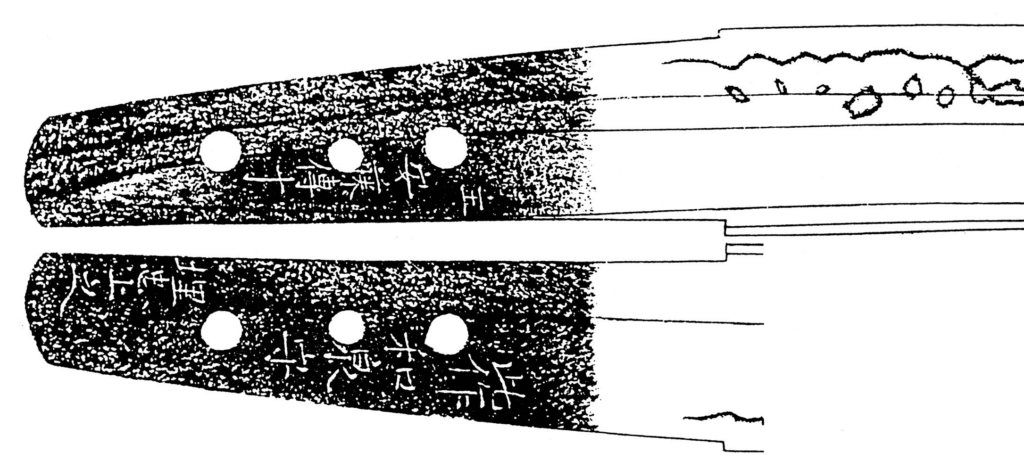

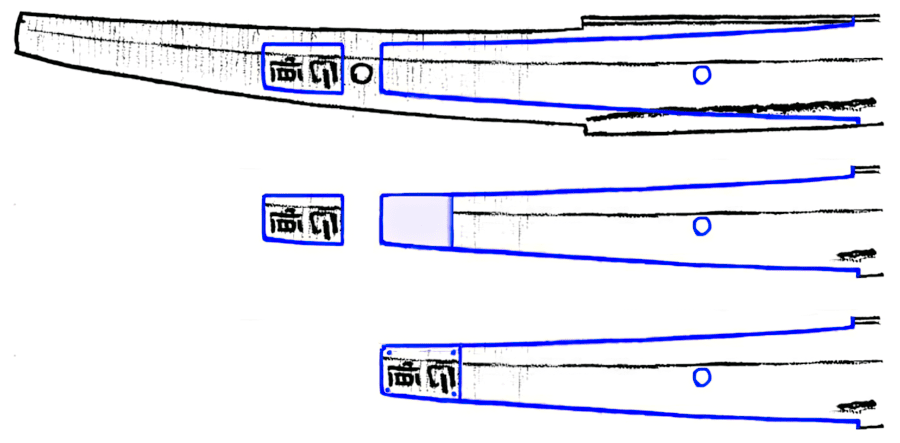

15. Orikaeshi-Mei

When a blade is shortened, the mei can be lost, but it can also be preserved by various means. An orikaeshi-mei (折り返し銘) means turned-back or folded-over signature. The part of the tang originally bearing the signature is thinned and folded back onto the opposite side to shorten the tang. As a result, the orikaeshi-mei appears upside down on the opposite part of the tang.

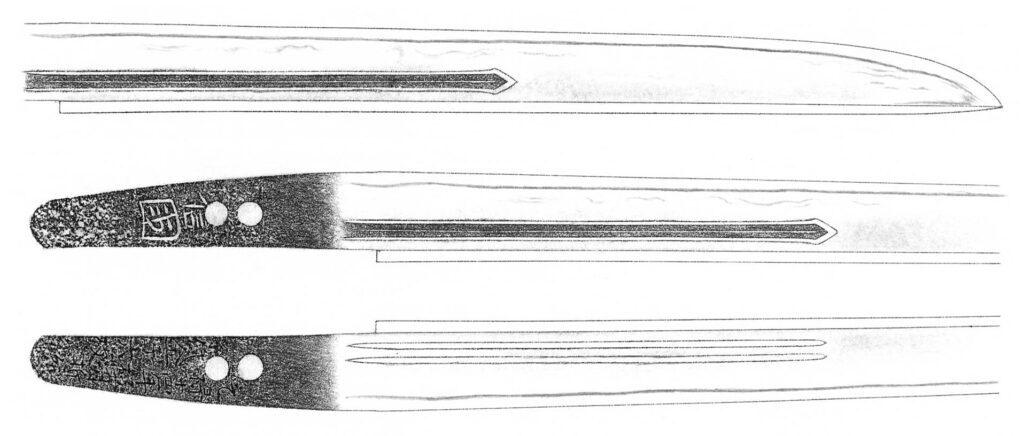

16. Gaku-Mei or Tanzaku-Mei

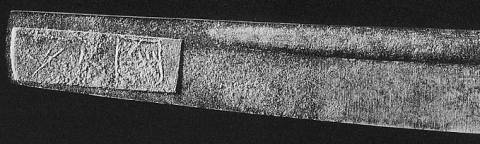

Gaku-mei (額銘) or framed signature is another method of retaining the original signature after shortening the blade. It is also known as tanzaku-mei (短冊銘) due to its resemblance of the small vertical poem cards (tanzaku).

The gaku-mei is often found on blades that have been greatly shortened (o-suriage), in which the rectangular part of metal containing the original signature is cut from the discarded tang and inlaid onto the newly reshaped tang.

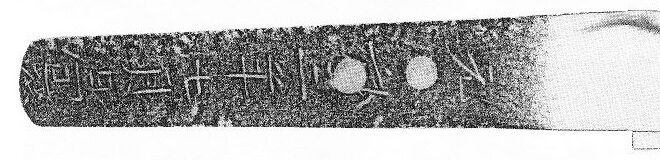

17. Hari-Mei or Haritsuke-Mei

Hari-mei (貼り銘) or haritsuke-mei (貼付け銘) means patched signature. It is commonly found on greatly shortened blades (ō-suriage), where the part of metal bearing the original mei is cut out and attached to the newly formed end of the tang (nakagojiri) using small rivets.

Translating and Assessing the Authenticity of Mei

For the specific translation of a mei and signature assessments, Mr. Markus Sesko is an expert in Japanese arms and armor and a member of NBTHK (Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords). A mei can be assessed to help determine if it is authentic (shôshin) or a forgery (gimei). However, Japanese blades are never appraised based solely on their signature.

In Japan, recognized organizations like NBTHK and NTHK conduct shinsa, the formal appraisal and evaluation of swords. For instance, swords assessed by the NBTHK may be granted appraisal papers known as kantei-sho, documenting the judges’ opinions on their quality and value. Some blades may not pass shinsa if they bear a false signature or if they are in poor condition, have poor polish, and such.