Exploring the Types of Menuki Ornaments and Their History

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Menuki are sword-grip ornaments on Japanese swords and daggers. These decorative fittings have evolved through history both in function and design. Like most Japanese sword fittings, these metal ornaments have become art pieces and collector’s items.

Different Types of Menuki

Throughout history, menuki ornaments reflected traditional Japanese craftsmanship and metalworking. While most menuki today are purely ornamental, earlier versions functioned as both peg and ornament. Some historians and collectors may use specific terminologies to describe menuki based on their function, design, and placement on the hilt.

1. Makoto-menuki

The term makoto-menuki (真目貫 or 誠目貫) literally means true menuki. It refers to the early menuki that served as both an ornamental headpiece and a mekugi peg to secure the hilt on the tang.

Having been around since the Nara Period, it is commonly found on early ceremonial tachi, especially the kara-tachi (lit. Tang tachi), which adhered to Tang ceremonial prescriptions. Most of these ceremonial tachi were covered with same (ray skin) and had unwrapped hilts, featuring a makoto-menuki with additional tawara-byo (straw bag-shaped rivets).

2. Tsubogasa-menuki

The term tsubogasa-menuki (壷笠目貫) translates as pot-hat menuki, referring to its rounded shape resembling pots or jugs with smaller tops (tsubogasa). It developed from early menuki that served as peg and ornament.

The front and back of the tsubogasa-menuki have identical designs, with both heads slightly larger than the mekugi-ana opening. Originally, they were symmetrically positioned on either side of the hilt, serving both a functional and decorative purpose. However, later examples became purely decorative and were positioned asymmetrically on the hilt.

3. In ́yō-kon menuki

The in’yō-kon menuki is another name for the two-piece menuki that served as a mekugi peg. It derives its name from the term kon (根), meaning root, referring to the stem at its backside. To prevent it from falling out, the two-piece in’yō-kon menuki features a hollow negative stem (in-kon) and a solid positive stem (yō-kon).

Originally, the positive stem was long enough to pass through the entire hilt and tang, connecting with the negative stem on the opposite side. Both stems featured small holes through which a leather string, metal wire, or pin could pass to prevent them from separating. As menuki transitioned into purely decorative elements, these stems lost their practical function.

The in’yō-kon menuki were made throughout the Edo period, featuring stems that followed the earlier designs but no longer served any practical purpose. These menuki can be seen on Edo-period tanto daggers, as well as on the later guntō military swords used by the Japanese army and navy after the dissolution of the samurai class.

4. Naga-menuki

The naga-menuki (長目貫) features the form of a kenukigata-tachi openwork design and is also known as ō-menuki (大目貫), meaning large menuki. The kenukigata-tachi is recognized for its unique hilt opening resembling tweezers (kenuki). This type of sword emerged during the Heian period and was occasionally used in ceremonies during the early Muromachi period.

Later on, these swords evolved into models with normal hilts without openings, but featured a large menuki resembling the kenukigata-tachi openwork design. These swords are referred to as kenukigata-menuki no tachi and were occasionally worn as ceremonial swords during the Edo period.

5. Sora-menuki

The term sora-menuki (そら目貫 or 空目貫) translates as empty or imitation menuki. It refers to the purely ornamental menuki, differentiating it from the makoto-menuki that functioned as a mekugi peg. It is also known as kazari-menuki (飾目貫) and does not have a stem or root.

These sora-menuki emerged during the Nanbokucho period onwards, often mounted on tachi and uchigatana with wrapped hilts designed for battlefield use. In the Edo period, they were also used on unwrapped, same-covered tanto hilts. In fact, the majority of existing koshirae feature this type of menuki.

6. Dashi-menuki

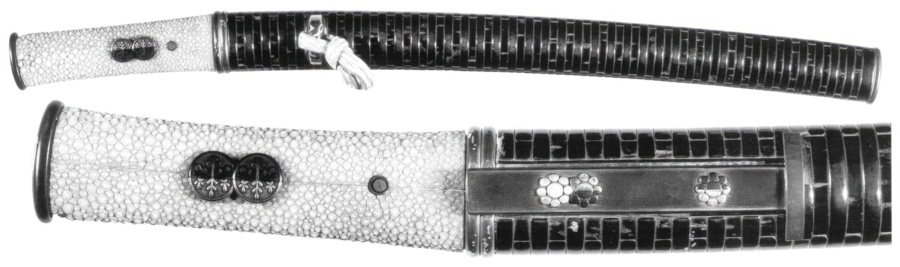

The term dashi-menuki (出目貫) means exposed menuki. It is also referred to as hari-menuki (glued menuki) or uki-menuki (floating menuki). These menuki can be found on unwrapped, same-covered hilts of tanto daggers and koshigatana, which is an all-purpose weapon and a companion blade to the tachi.

Some were attached onto the same (ray skin) of unwrapped hilts, usually using a sticky lacquer known as seshime-urushi. Others were positioned above the braided hilt wrapping and secured with a cord looped around on each side. Some were positioned at the center on the evenly wrapped area of a katate-maki.

7. Gyaku-menuki

The Japanese term gyaku (逆) literally means reversed or inverted. Thus, the gyaku-menuki (逆目貫) refers to a menuki attached traditionally, but in reverse. In this arrangement, the menuki on the front side (omote) of the sword faces towards the kashira (pommel cap), unlike the usual case where it faces towards the fuchi (ferrule or hilt collar).

A gyaku-menuki was first and often seen on Yagyū-koshirae, popularized by the Yagyū school. Its placement on the hilt is derived from the idea that the protruding menuki should be positioned in the palm of the swordsman when gripping the sword hilt. Therefore, typical Yagyū-koshirae feature the menuki in reversed positions compared to the typical placement and have a ribbed scabbard.

A Brief History of Menuki

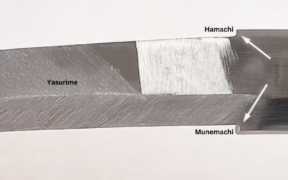

The menuki developed from the mekugi peg, which secures the tang in the hilt through the mekugi-ana opening. Over time, the menuki evolved into purely decorative elements, while providing a better grip at the hilt. In the case of the tachi, menuki were placed about one hand’s width from the fuchi (ferrule or hilt collar) on the front side and the kashira (pommel cap) on the back side.

In the Momoyama period, it became a tradition for the emperor, shogun, and daimyo to reward valued retainers with swords. This led to the production of elaborate and expensive menuki and other sword mountings, crafted from fine materials using sophisticated metalworking techniques.

By the Edo period, it became mandatory for a samurai to wear a daisho fitted with mitokoromono—a set of menuki, kozuka, and kogai in matching material, manufacturing technique, and design. These were often made by the Goto family, who were renowned for making fine sword fittings for the shogun and the samurai.

It was also during the Edo period that sword fittings, including the menuki, became collectible items. Chests housing these hilt ornaments were often exchanged as gifts among wealthy samurai on special occasions, such as marriage, the birth of a child, or a promotion in rank.