How Yasurime on a Tang Helps in Appraising Japanese Swords

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Yasurime, decorative file patterns on the tang of a Japanese blade, are more than just an aesthetic detail—it’s a vital clue in uncovering a sword’s history. These patterns, unique to individual swordsmiths, schools, and historical periods, serve as a silent storyteller, revealing the blade’s age and origin.

Join us as we delve into the fascinating world of yasurime, exploring its appearance, the various types, and its critical role in the art of sword appraisal.

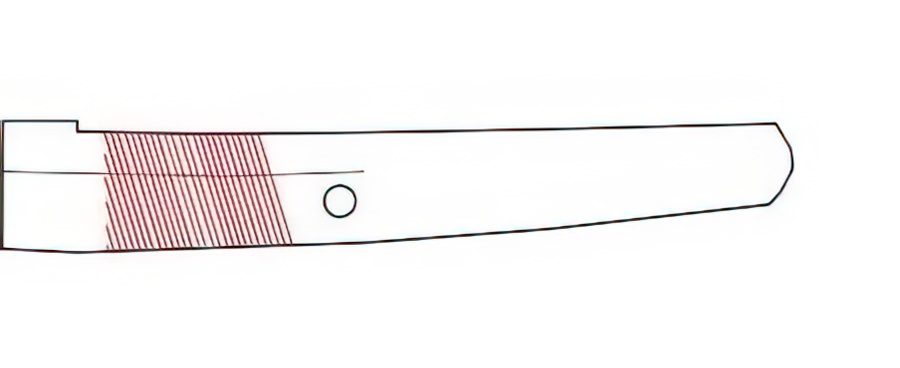

Appearance of Yasurime

A Japanese sword tang features yasurime (distinctive file marks) next to the habaki (blade collar). Typically with the same pattern on both sides, these marks vary in depth, thickness, and spacing depending on the file used by the swordsmith.

However, each of the following surfaces of the tang must be filed separately:

- ji (steel surface of the sword)

- shinogi-ji (surface of the blade between the shinogi ridge line and the back surface)

- mune (unsharpened back surface of the blade).

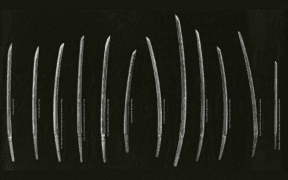

Types of Yasurime

The terms “yasuri (file) and yasurime (file marks) describe the filing patterns or strokes on the tang. The style of filing varies in different swordsmiths, schools, and periods.

1. Kiri (Horizontal)

The most popular yasurime is Kiri yasurime, also known as yoko yasurime. They are often found on blades from Awataguchi and Rai schools of the Yamashiro tradition and the Shikkake school of the Yamato tradition.

- Pattern: Straight and horizontal, filed from edge to back

2. Katte Sagari (Downward Slanting)

Katte sagari is the second most popular style throughout all periods and is also found on blades from the Awataguchi, Rai, and Shikkake sword making schools.

- Pattern: Slanting from top left to bottom right at a shallow angle, less than 45 degrees

3. Katte Agari (Upward Slanting)

Katte agari is the opposite of katte sagari.

- Pattern: Slanting from bottom left to top right at a shallow angle, less than 45 degrees.

4. Sujikai (Diagonal)

Sujikai is similar to katte sagari, the only difference being that it slants at a greater degree. The even steeper variety is o-sujikai (great sujikai), seen on blades by the Aoe, Samonji, and Horikawa schools.

- Pattern: Slants from upper left to lower right, but at a steeper degree than katte sagari.

Meanwhile, saka o-sujikai is similar to katte agari, but slants at a greater degree. It appears only on Shinto blades, such as those forged by swordsmith Horikawa Kuniyasu.

- Pattern: Slats from bottom left to top right, but at a steeper degree than katte agari.

5. Takanoha (Hawk’s Feather)

Takanoha file marks resemble a hawk’s feather. These V-shaped file marks were seen in blades of the Yamato tradition and related sword making schools in the Koto era.

- Pattern: Slanting down from the tang’s centerline to outer edge. The ridged side of the tang (shinoji-ji) slants downward to the right, while the edge side of the tang (hiraji) slants downward to the left.

The opposite of the takanoha is saka takanoha, featuring an inverted V-shaped pattern. It is mainly seen in blades from the Yamato and Mino provinces.

- Pattern: The file marks on the shinogi-ji slant upwards to the right, while those on the hiraji slant upwards to the left.

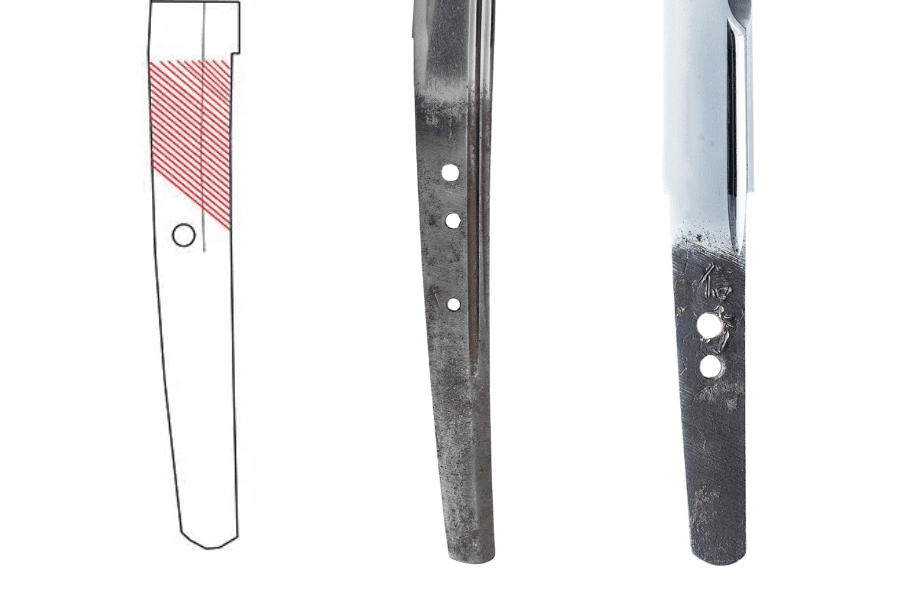

6. Kesho (Cosmetic File Marks)

Kesho yasurime or kesho yasuri translates to “cosmetic file marks”, appearing only on Shinto and later blades, though there were variations in blades of various swordsmiths and schools. It was only used by swordsmiths of the Edo period, from 1603 to 1867 and after.

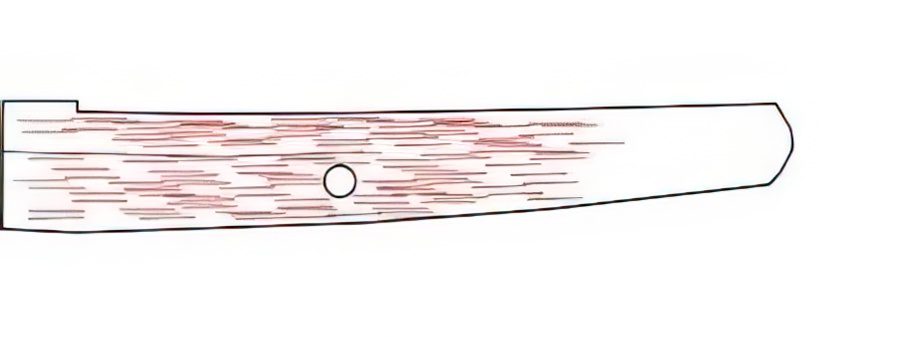

- Pattern: Combination of slants covering most of the tang and horizontal marks. File marks can have two (nidan-kesho) or three (sandan-kesho) directions.

7. Higaki (Cross-Hatched)

Since the term higaki refers to a fence made of thin strips of Japanese cypress, the higaki yasurime is similar to the woven pattern on the fence. It is widely seen on blades from the Yamato and Mino traditions and the Naminohira school in the Koto era.

- Pattern: Cross-hatched pattern, with slanted file marks going in both directions

8. Sensuki (Shaved)

Sensuki yasurime is created using a sen (a tool similar to a plane for shaping wood). Since early sword tangs (usually double-edged ken or tsurugi) were shaved rather than filed, this style is mainly seen on jokoto blades (pre-1000 CE). Sensuki also appeared on early Koto-era swords and sometimes on Mino blades from the Muromachi period (1338 – 1573 CE)

- Pattern: Irregular vertical strokes

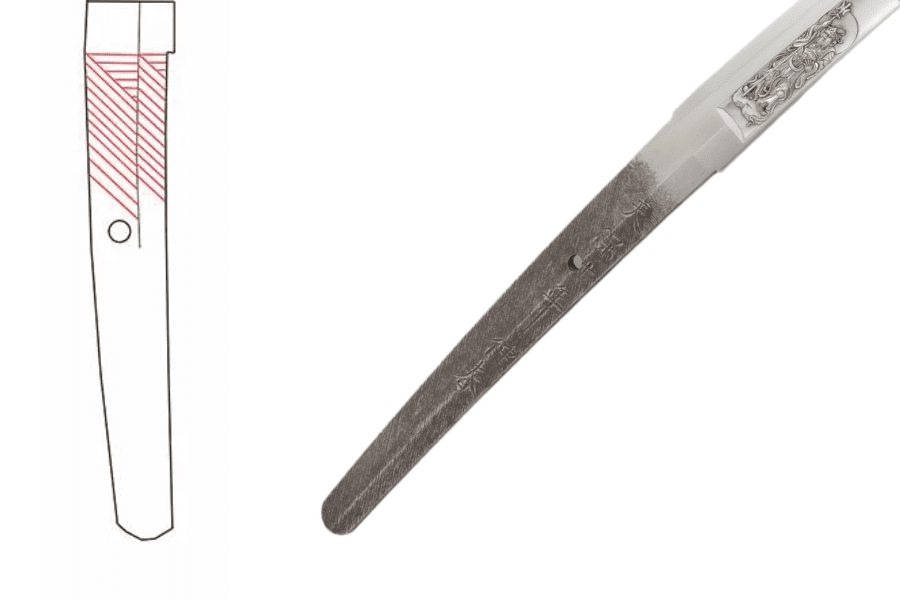

Why Is Yasurime Crucial for Sword Appraisal?

The yasurime can reveal significant information when appraising a Japanese sword as the file marks differ based on the historical period, swordsmith’s techniques, and various swordmaking schools, aiding in understanding the blade’s origins and authenticity.

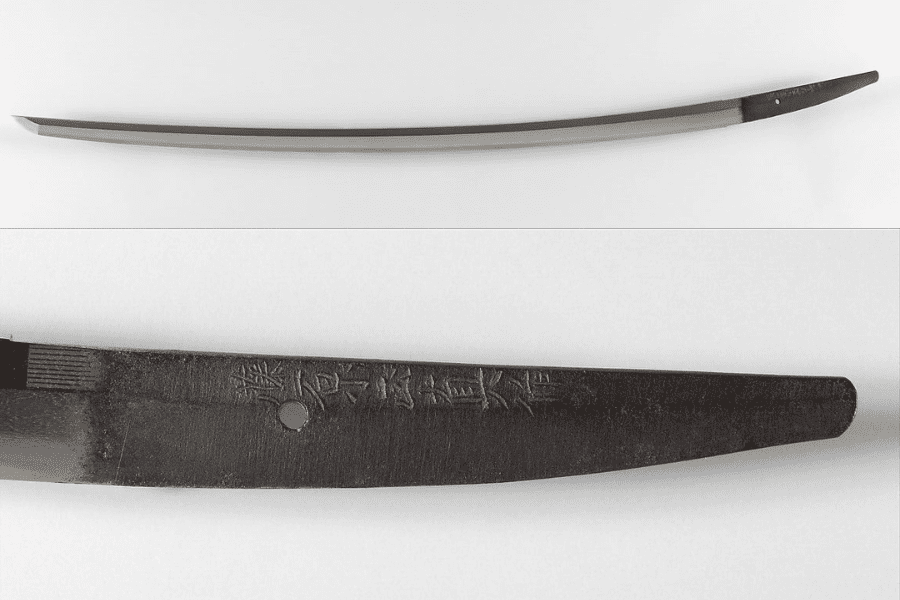

Since a Japanese sword’s tang is never cleaned or polished during its lifetime, the clarity of the yasurime, presence of remaining file marks, and color of the rust that accumulates are key when dating a blade.

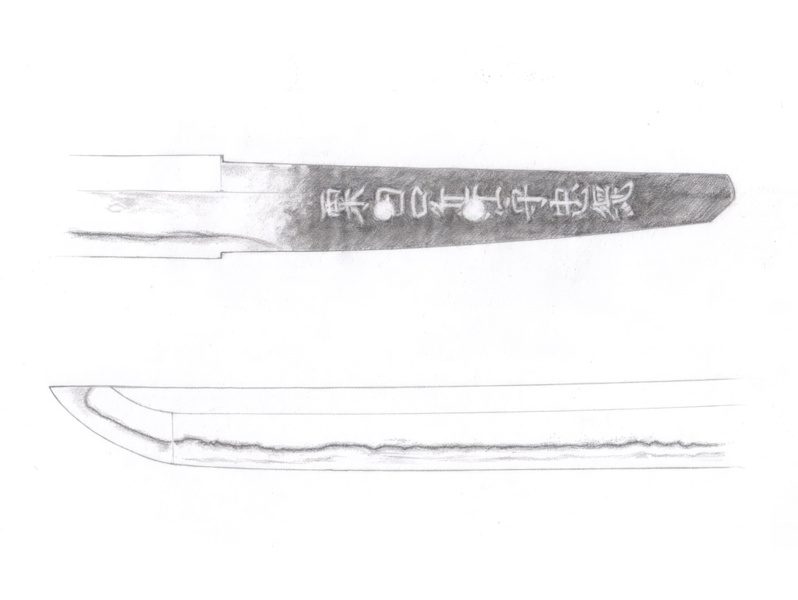

The yasurime can also be examined through oshigata, highly detailed drawings of Japanese blades that are more accurate than photographs. A well-drawn oshigata can help in identifying specific swords even centuries after its creation.

However, expert Markus Sesko warns that oshigata can be misleading, emphasizing that there is no substitute for examining the blade in person.

Yasurime Beyond Sword Blades

Yasurime are not limited to swords and are featured in other Japanese bladed weapons including:

- tanto daggers

- polearms such as the yari (spear) and naginata (glaive)

- jumonji yari (a cross-shaped spear variant with curved protrusions resembling cow horns).

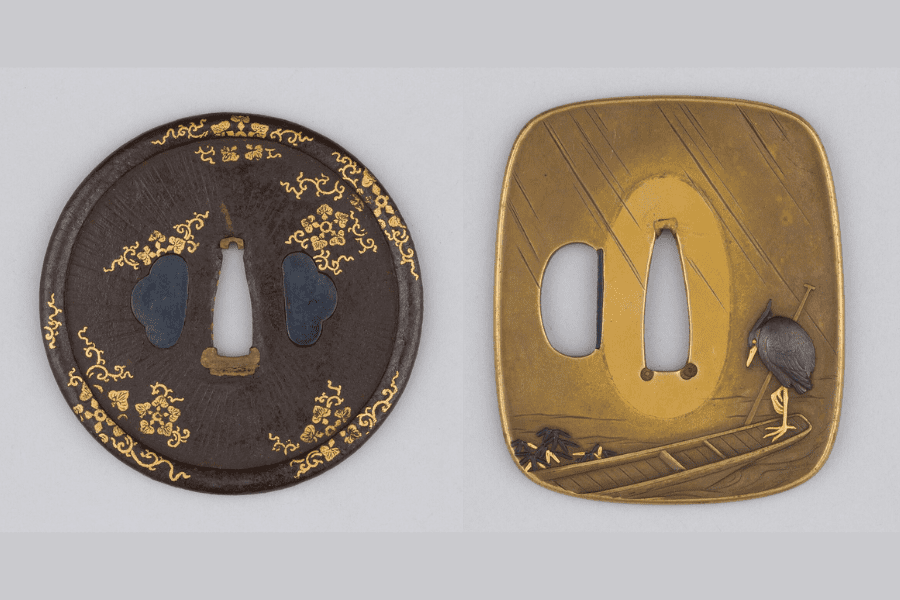

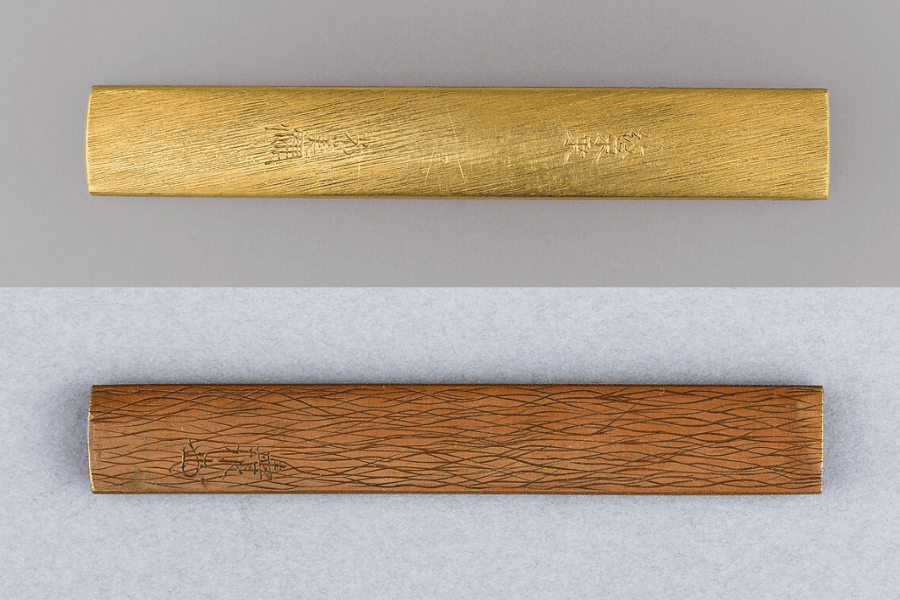

The term yasurime can also refer to file marks on sword fittings, such as the tsuba (sword guard), kozuka (utility knife handle), and kogai (hairdressing tool).

Common types of file marks on sword guards include amida-yasurime (resembling sun rays in a radial pattern) and okina-yasurime (concentric circles similar to marks left by a potter’s wheel).

The backs of kozuka and kogai are often decorated with yasurime. The most common pattern is sujikai-yasurime (slanting strokes). Others include nekogaki-yasurime (resembling cat scratches) and matsukawa-yasurime (resembling the texture of pine bark).