13 Types of Arming Swords and Their Historical Evolution

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

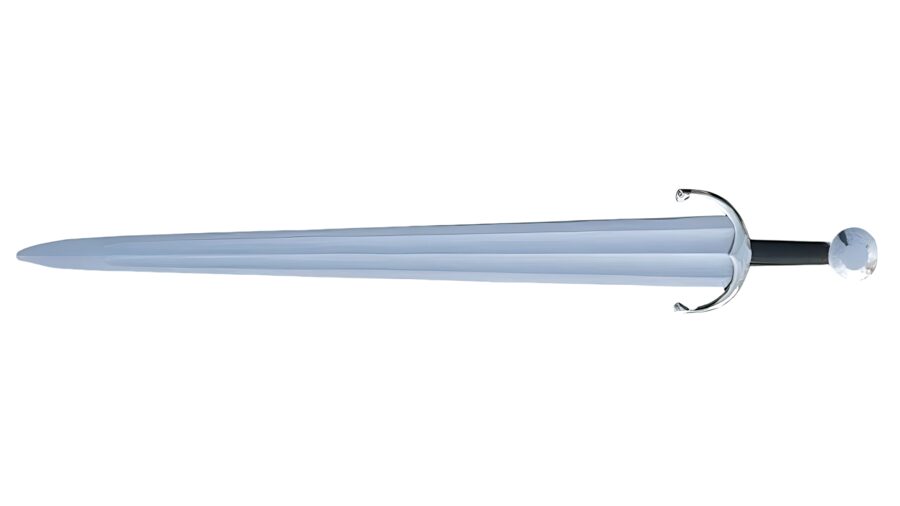

The Arming Sword is one of Europe’s most iconic and influential blades once used during the Hundred Years’ War, Crusades, War of the Roses, and more. Playing a central role in medieval warfare, it is available in 13 different types with each representing a different stage in its evolution to combat specific enemies.

This article explores the arming sword, its characteristics, and its 13 variations across the centuries.

What is an “Arming Sword”?

Used in Europe from the 10th to 16th centuries, the arming sword earned its name from having each soldier being armed with one. Due to its simple yet effective design, it became one of the most influential swords in Europe.

In a thesis on European medieval swords, the Worcester Polytechnic Institute noted that,

“This basic yet sturdy design led to the arming sword being one of the most iconic weapons of the medieval period, especially concerning its close association with knights.”

Characteristics and Traits

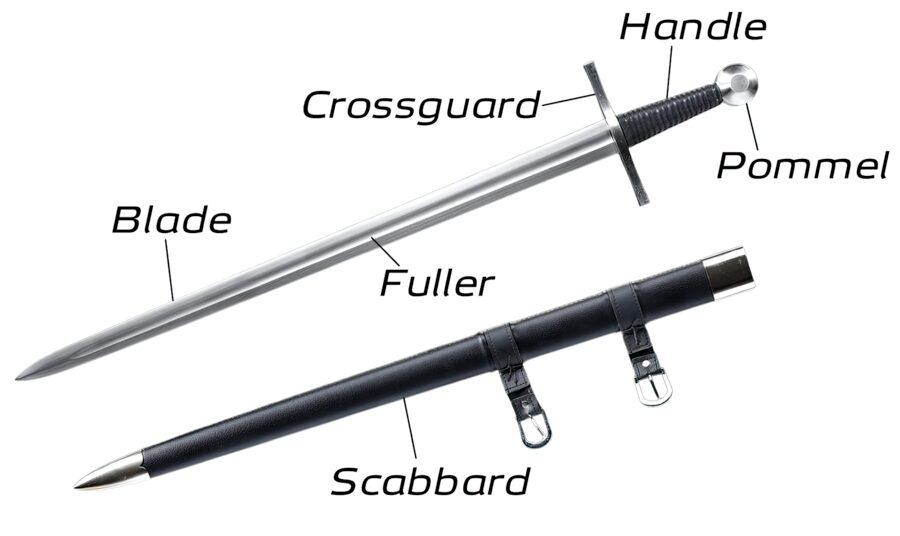

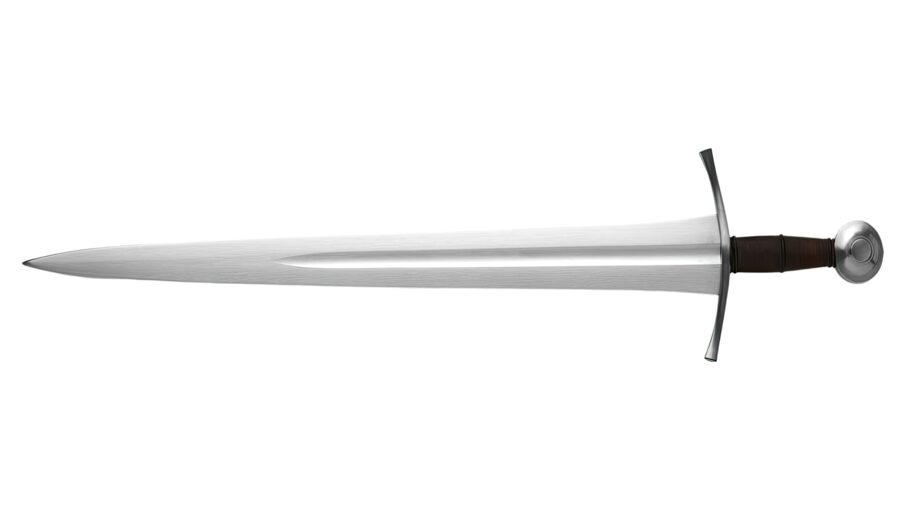

Although arming swords can vary in shape and design, they generally have straight double-edged blades with a fuller or rib running down its center, parallel edges, and some taper towards the tip.

The handles of arming swords are always one-handed, typically with a large pommel. These swords are some of the first European swords to feature the iconic crossguard.

Types of Arming Swords

Arming swords can be classified based on their different blades and handle characteristics which evolved from adapting to new armor and fighting tactics. These categories were created by Ewart Oakeshott, a historian who collected and researched European swords.

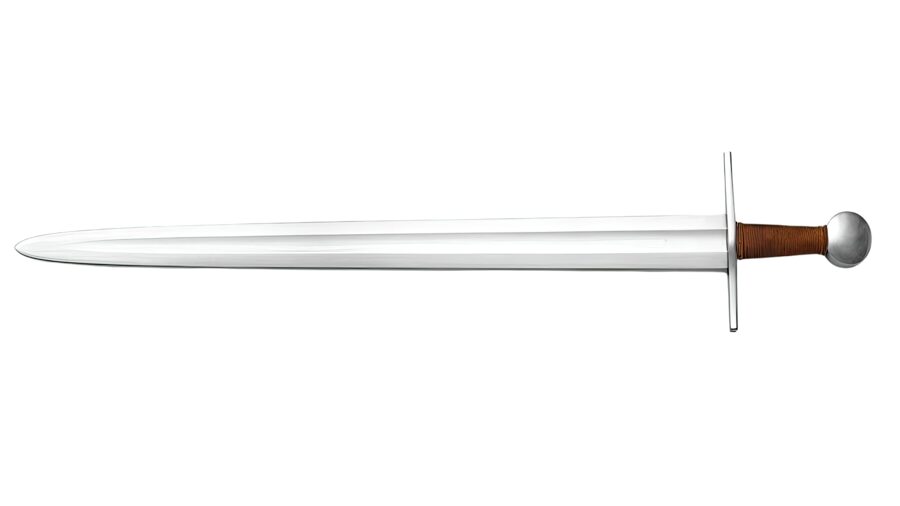

Type X

Type X is the earliest type of arming sword, inspired by the Viking sword. Popular among knights from the 9th to 13th centuries to combat mail armor, type X blades feature a lenticular, simple design with a long fuller and almost parallel edges towards the tip. A straight crossguard for protection is typical.

Type Xa

Type Xa was recently a separate addition as it differs very little from Type X. Featuring similar characteristics, type Xa blades are slightly longer, most likely favored by cavalry troops.

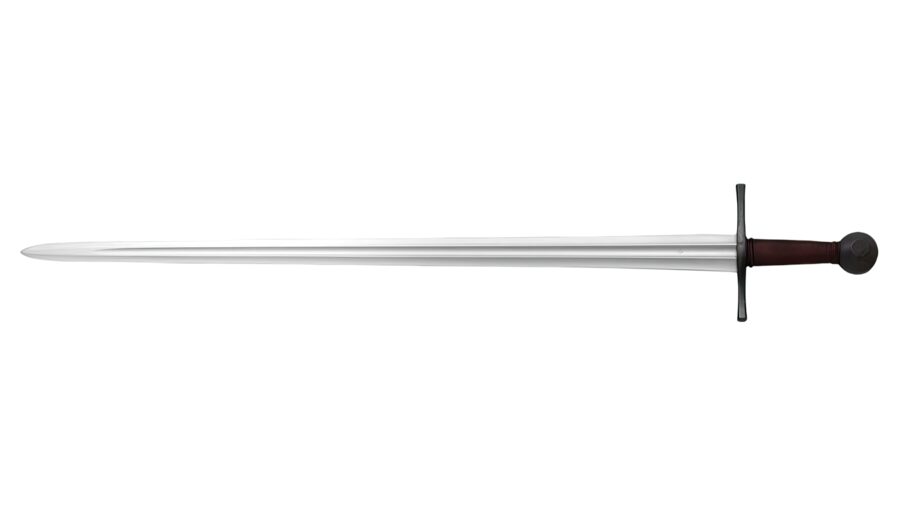

Type XI

Type XI arming swords are some of the most popular early knightly swords. Used during the 12th century, especially by knights mounted on horses, they featured longer, slimmer blades that were thinner toward the tip.

These swords excelled at slashing and could also be used to thrust from horseback. Like type X, they have a lenticular design but featured a longer crossguard with larger pommels. Due to their popularity during the Crusades, it is sometimes known as a Crusader Sword.

Type XIa

Although type XIa and XI have the same hilt characteristics, type XIa have significantly broader blades, making them very effective chopping and cutting melee weapons, especially against unarmored opponents.

Type XII

Popular from the 12th to 14th centuries, type XII was one of the first cut-and-thrust one-handed medieval weapons, created to adapt to armor improvement.

The blade has a broad base with one or multiple fullers and is fairly pointy at the tip. Meanwhile, the crossguard could be as long as the previous arming swords mentioned above, possibly narrowing from the outside toward the blade to improve maneuverability in combat.

Type XIIIb

Type XIII, known as the medieval Great Sword, were very large two-handed weapons primarily focused on cutting and slashing, especially practical during and after the Crusades.

On the other hand, the arming sword subtype XIIIb features an equally broad and heavy blade with a short fuller, but it has a one-handed handle.

Type XIV

Type XIV swords were proper cut and thrust weapons, combining the best features of both designs. This made them popular from the 13th to 14th centuries, an era when plate armor was slowly becoming a real threat.

The blade has a broad base, wide and deep fuller, and very pointy tip. Since the blade is shorter than the other types, it is more precise when thrusting through mail or plate armor gaps.

Type XV

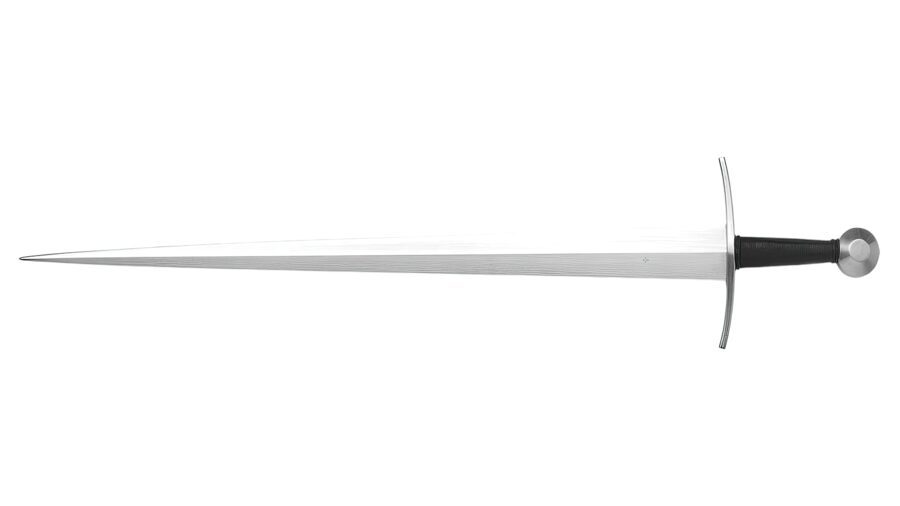

With the victory of plate armor over swords, arming swords too evolved. Type XV was the first model designed to counter them and was somewhat successful from the 14th to 16th centuries.

Its strongly tapering blades have a very acute point and the famed mid-rib, which strengthens the rigidity of the blade, making it an excellent thrusting weapon capable of cutting.

They could be used with shields, as with previous models, but were also suitable for grappling.

Type XVIII

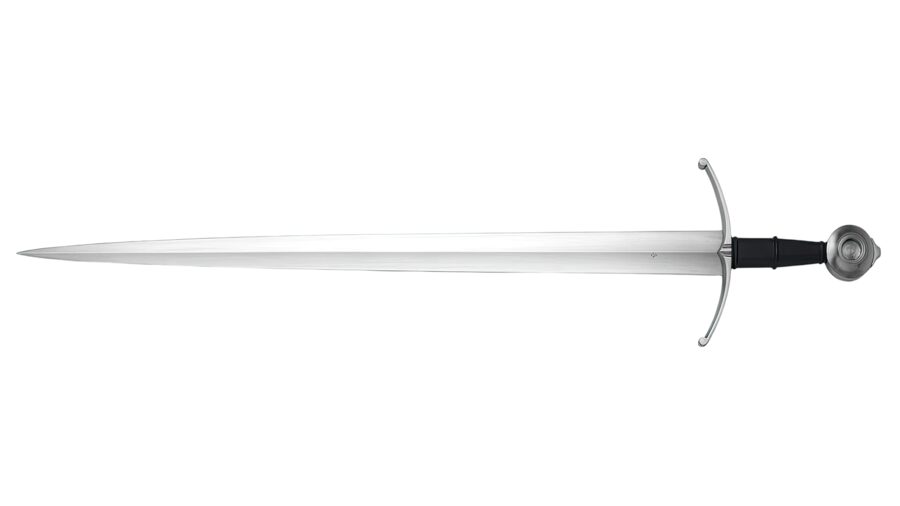

Combining features from earlier and newer models, the Type XVIII arming sword was used during the 15th and 16th centuries when lighter armor made a comeback.

These swords were cut and thrust types of weapons and were generally shorter than contemporary blades. Highly adaptable, they featured either a diamond hollow cross-section or a reinforced midrib.

XVIIId

Subtype XVIIId features one of the slimmest blade designs. Since they were lighter and easily used in thrusting attacks, they were often used for daily self-defense.

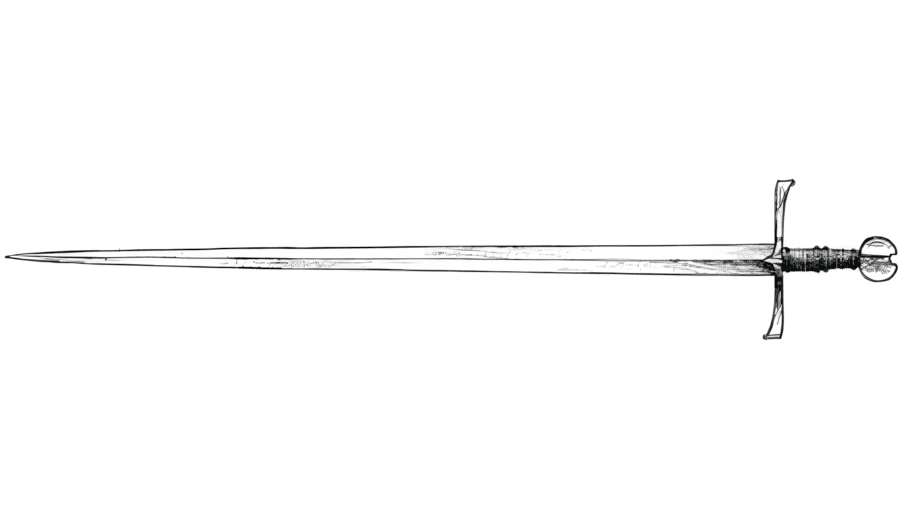

Type XIX

Type XIX arming swords were used throughout the 16th century as effective cut and thrust weapons that closely resembled previous models.

Featuring straight, almost parallel edges with a somewhat pointy tip, they featured elaborate hilts with ring fingers or a D-guard. Some also had multiple fullers and a ricasso—an unsharpened part near the guard for a more maneuverable grip in close combat.

Type XXI

The transitional type XXI emerged during the late 15th and 16th centuries among civilians for self-defense and as a fashionable accessory.

It incorporated features of earlier arming sword types with Renaissance elements such as a blade that tapered toward the tip, a broad base, and multiple fullers.

Type XXII

Type XXII was the final stage in the evolution of the arming sword, featuring a broader and heavier blade than its predecessors.

While it retained its combat potential, many believe that it was primarily designed for ceremonial purposes such as parades due to the elaborate decorations and multiple fullers.