Irish Sword Types: From Bronze to Ringed Pommel Swords

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

The Irish Sword is one of the most popular weapons today, known for its distinctive open-ring pommel hilt. Its unique shape and design were inspired by the types of blades that preceded it. Its development began as early as the Iron Age, with influences from Celtic designs from mainland Europe, carried through trade and conflict.

Over the centuries, the Irish sword evolved through various forms, reflecting the fighting styles and trends in history. This article explores some of the most significant sword types that contributed to the development of the Irish sword we know today.

Irish Ancient Swords

During the Bronze and Iron Ages, Irish swords typically had leaf-shaped blades, a common trait across Europe. The La Tene and Hallstatt swords are Celtic blades that were used extensively during the Iron Age in Europe.

In Ireland, these swords were shorter, likely due to the style of warfare in Ireland at the time. Additionally, the distinctive curving of the sword shoulders, which smoothly transitions from the tang to the blade along with the bell-shaped bronze guards set Irish swords apart from other weapons.

Etienne Rynne, historian and researcher of Irish swords said, “The radical difference in length from the Continental and British counterparts ranges from a lack of skill in metalworking, to a style of warfare in which the spear was paramount and the sword hardly used.”

Early Medieval Irish Swords

As early as the 2nd to 4th centuries CE, Irish swords evolved into two major groups, influenced by Roman and European sword groups at the time. Some researchers believe that these swords were used extensively until the 7th century CE.

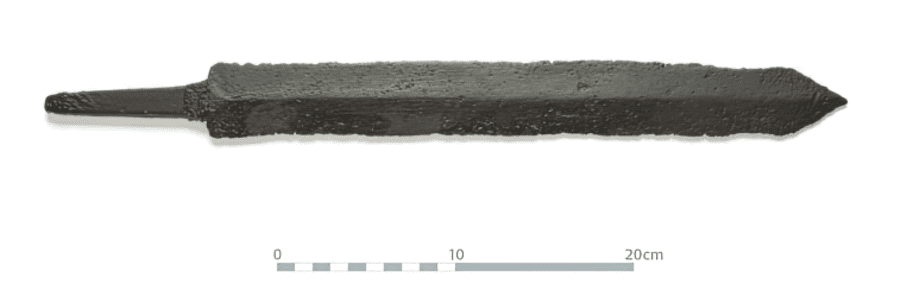

Group 1 – Irish Gladius

The Irish gladius is very similar to the Roman gladius, with one major difference—they are significantly shorter. In fact, the shortest surviving example measures a mere 14 inches (35 cm).

Featuring a straight double-edged blade with parallel edges, most examples have a waist in the center, resulting in a leaf-shaped profile that widens toward the tip.

Most of these have a blade cross-section that is lozenge-shaped and usually lacks a mid-rib. Their pommels are smaller and lighter, making the center of balance hear the blade’s tip.

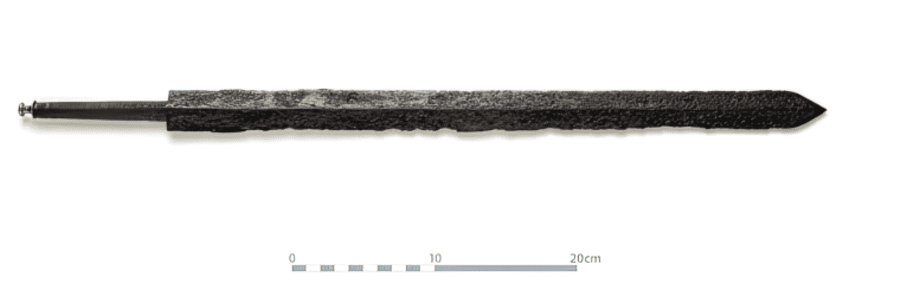

Group 2 – Irish Spatha

After the Roman era, the spatha, which was longer than the gladius, became the standard sword in Europe for many centuries. Like the Irish gladius, the Irish spatha, too, was shorter than its European counterpart with the longest surviving example measuring only 24.6 inches (62.5 cm). This is most likely due to the low use of cavalry in Ireland.

Also featuring a lozenge-shaped cross-section of the blade, these swords have parallel double-edged sides with some rare examples featuring a taper toward the tip. Due to the shorter length and possibly designed to be lighter, the pommels were usually small, either featuring a peen block button or a metal cap that held the handle together.

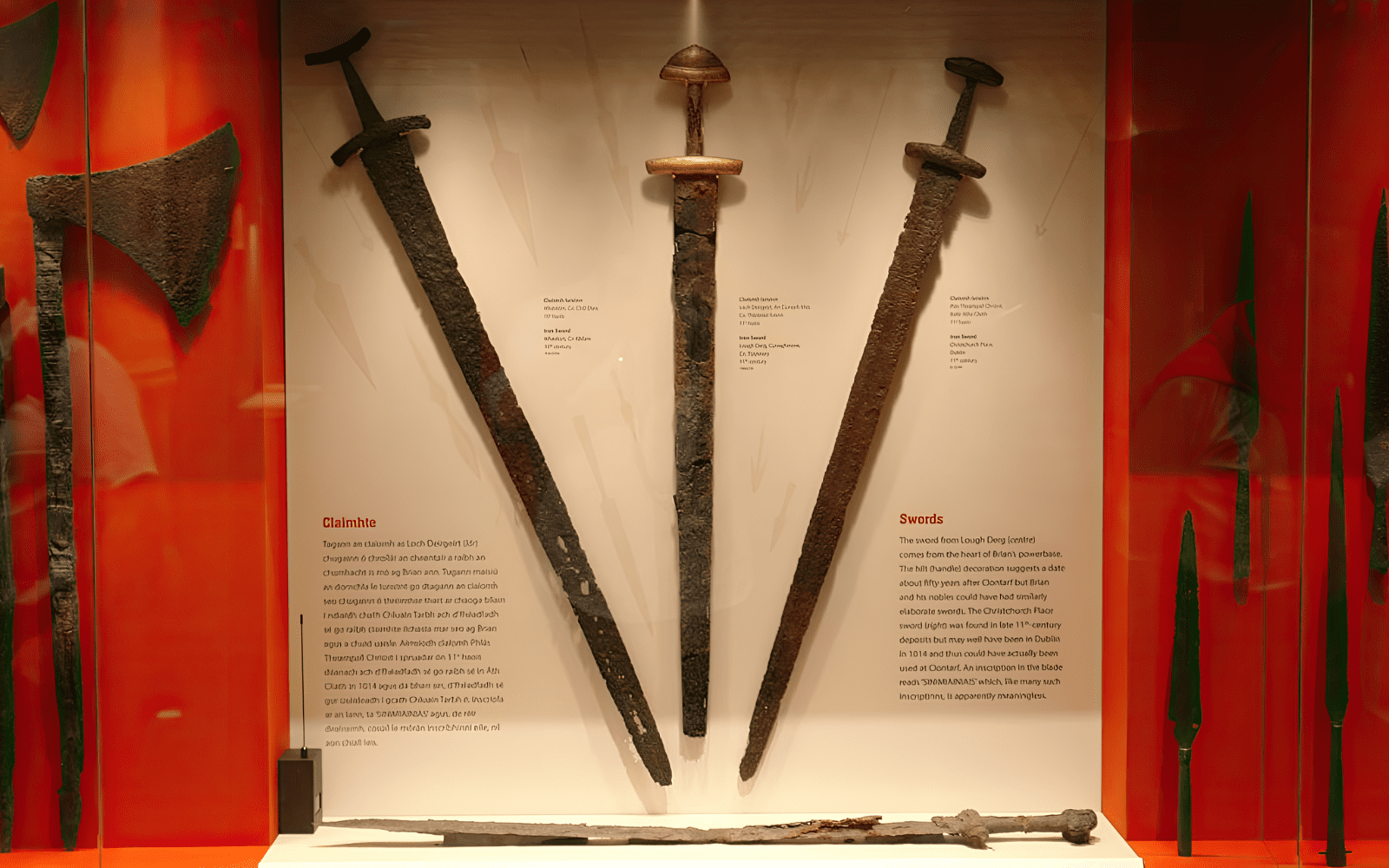

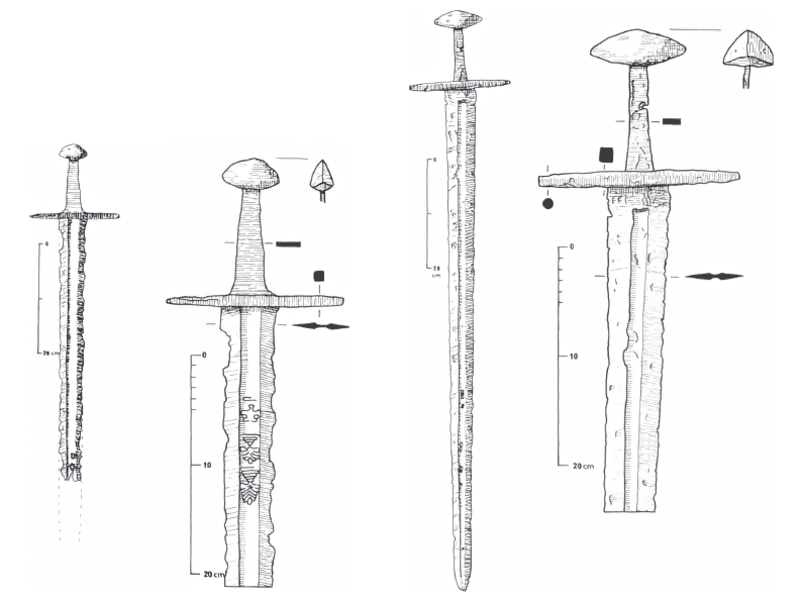

Group 3 – Irish Viking Swords

Like the gladius, the spatha soon declined and was replaced by the Carolingian sword, commonly known today as the Viking Sword. These swords are believed to have been brought by Viking raids.

Although some were produced locally, most had blades imported from Europe, which were then mounted on locally-made hilts. A popular example is the Ballinderry Sword, bearing the iconic Ulfberht mark, indicating that it was either inspired or imported by European blades.

Medieval & Modern Irish Swords

During the Middle Ages and after the Viking Age conquests, Irish swordsmiths produced several unique swords where one of the most recognizable traits being the open-ringed pommel.

Group 1 – Irish Arming Swords

Arming swords were widely used across Europe between the 12th to 14th centuries. The Irish variant shares many of the same features including the straight, double-edged blade and European crossguard.

However, the Irish versions tend to have a broader blade and almost always come with a fuller, making them effective for chopping and against mail armor. Having existed before the Norman Invasion of Ireland, they soon became the standard and norm.

Group 2 – Irish Hiberno/Scottish Swords

During the 15th and 16th centuries, a hybrid sword created in Scotland was brought to Ireland by mercenaries. These swords, including the Gallowglass, are much longer and can be wielded with both hands.

Featuring long hilts with iconic down-sloping crossguards, some even have quatrefoil and triangular terminals at the ends. The pommels tend to be hollow, a characteristic unique to the region. While the blade could have been imported, the hilts were made locally.

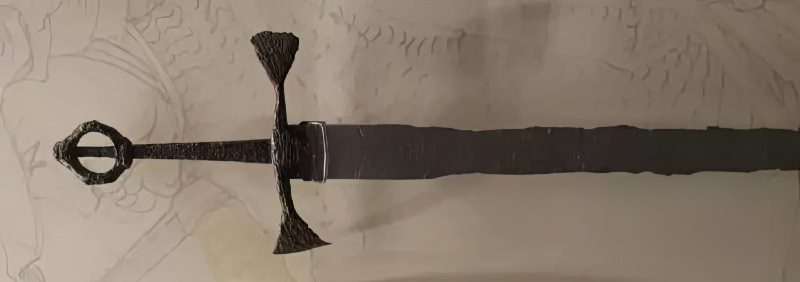

Group 3 – Irish Ring-Pommeled Swords

By the 16th century, the open-ring pommel became a distinctive feature of Irish sword design with a hallmark ring-shaped pommel and an iron strip at the center. Although rarely seen in Europe, this design became iconic in Ireland, mostly linked with light infantry.

While the blades were from the previous groups with slight variations such as multiple fullers and a ricasso, the hilts are unique. Additionally, the crossguard typically extends outward in a triangular form, offering greater hand protection during combat.