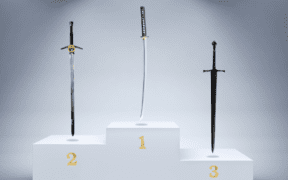

39 Sword Steel Types: A Guide into Metallurgical Characteristics

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

There are various types of steel suitable for swords, each with unique qualities for different needs like tameshigiri or decorative pieces resistant to rust. The distinct composition and craftsmanship of these steels distinguish them.

Knowing these differences is vital for collectors or those assessing a sword’s quality before purchase.

This article will examine popular steel swords, exploring their usefulness, characteristics, and the ideal sword type for each purpose.

EXPERT INISGHTThe choice of steel used in a sword determines much of how it will function – matching the steel to your needs is critical to matching your sword to you. From plain carbon, mono-tempered blades to folded, laminated, and differentially hardened blades, a vast variety of options are available at every budget and for every need, whether you intend to cut, spar or display your blade.

| Carbon Steel | Spring Steel | Tool Steel | Stainless Steel | Folded Steel | Alloy & Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1045 | 5160 | L6 | Manganese | Damascus | San Mai |

| 1050 / 1055 | 5166 | S7 | Niolox | Tamahagane | Wootz |

| 1060 / 1065 | 9260 | Sleipner | K120C | Laminated | HWS – 1S Alloy |

| 1070 / 1075 | EN45 | T10 | Q235 | HWS – 2S Alloy | |

| 1080 / 1085 | EN42J | K720 | 3CR13 | Aluminum | |

| 1090 / 1095 | 65Mn | 2CR13 | Synthetic | ||

| 1566 | 420J2 | ||||

| 6150 | 420HC | ||||

| EN9 | 440C | ||||

| DNH7 | AUS-6-8-10 |

Carbon Steel

Flexible and durable, high-carbon steel swords are great for beginners in both Japanese and Medieval European styles.

Requiring regular maintenance, these blades, coded as 10XX, have varying carbon content that dictates their hardness.

Higher carbon means a sharper, more durable edge, but these swords need consistent oiling to prevent rust, especially in humid environments.

1045

1045 steel, with its 0.45% carbon content, is good for making lighter, budget-friendly swords. This softer steel is easier to work with and costs less.

It doesn’t stay as sharp as harder steels, but with the right tempering, it can still hold an edge well enough.

Despite being the cheapest type of carbon steel, a skilled blacksmith can turn it into a solid, usable battle-ready sword, though it may not stay sharp as long as more expensive options.

1050 / 1055

1050 and 1055 high carbon steels, with their increased carbon content, are great for blades needing better impact resistance and durability at a reasonable price.

These steels are less prone to brittleness, thanks to added manganese, and achieve uniform hardness and excellent shock resistance when tempered by skilled craftsmen.

Slightly more expensive, they offer a sharper, more durable edge, and are a top choice for those willing to pay a bit more for superior quality.

1060 / 1065

1060 and 1065 steels, with 0.60% and 0.65% carbon, are ideal for swords due to their balance of durability, hardness, and edge retention.

These steels create practical, long-lasting cutting swords without the high price of more specialized steels.

1060 steel, especially popular, offers a good mix of flexibility and hardness, perfect for various uses. It’s often used in Katanas, where clay tempering gives a hard edge and flexible core, plus a distinctive hamon.

1070 / 1075

1070 and 1075 steels are like high-performance batteries for swords – they stay sharp longer and are strong.

They’re an upgrade from the versatile 1060 and 1065 steels, focusing more on sharpness.

These steels are similar to a kitchen knife that rarely needs sharpening but require extra care to avoid rust and are somewhat more delicate.

If you want a sword that maintains its edge with minimal sharpening and you’re willing to give it extra attention, 1075 steel is an excellent choice.

1080 / 1085

1080 high carbon steel, while less common, offers a good middle ground. It keeps its edge sharper for longer than the lower carbon steels we’ve discussed.

But there’s a trade-off: it’s more brittle, meaning it’s easier to break or chip, especially if not used correctly.

This brittleness, though useful in some scenarios, is why it’s not as popular. However, for those who are experienced in cutting and have refined their techniques, 1080 steel can be an excellent choice.

It suits users who value sharpness and are skilled enough to handle the steel’s delicate nature.

1090 / 1095

Tempered 1095 high carbon steel, containing 0.95% carbon, is outstanding for maintaining an extremely sharp edge, making it a top choice for edge retention.

This steel, however, is somewhat more prone to chipping than lower carbon variants and demands careful handling, particularly with longer swords where incorrect techniques can be detrimental.

This susceptibility to chipping is less of an issue in differentially hardened blades, which balance sharpness with flexibility.

Shorter swords, such as the Gladius or Xiphos, also perform well with this sturdy steel.

Despite needing extra care to prevent rust, 1095 steel is ideal for experienced users seeking a consistently sharp, durable edge for frequent use.

1566

1566 spring steel, with about 0.60 – 0.70% carbon and a significant amount of manganese (0.85 – 1.15%), is a favorite among swordsmiths.

This blend results in a steel that hardens deeply and evenly once tempered. The outcome is a blade that’s not only tough but also stays sharp even with heavy use, perfect for cutting practice.

This high-carbon and manganese combination makes the steel ideal for both differentially hardened Japanese and European medieval swords, as well as other functional swords.

It excels in toughness and keeping an edge sharp. In short, 1566 steel is an excellent choice for any functional sword, offering a great balance of durability and consistent sharpness.

6150

6150 steel is like a tough, shock-resistant material, mixed with chromium and vanadium.

It’s strong, even with a bit less carbon than other sword steels, balancing strength with flexibility. This makes it ideal for heavy-duty tasks.

Sword makers like Arms & Armor and Albion Armorers prefer 6150 for its durability. It’s similar to 5160 steel but stronger due to vanadium, although not quite as hard.

EN9

EN9 steel, with about 0.50 – 0.60% carbon and 0.50 – 0.80% manganese, is quite similar to popular steels like 1050 or 1055.

It’s a material that can be toughened up through heating and cooling processes, making it very durable and resistant to wear and tear.

This toughness and longevity make it a good choice for making strong, reliable tools and equipment.

Its performance is on par with the well-known 1050 or 1055 steels, which are also prized for their durability.

DNH7

DNH7 is a type of high-carbon steel, much like the 1075 steel, known for its strength. It undergoes a special process that makes the blade’s edge stay sharp for a long time, making it a top choice for Asian swords.

DNH7 is also versatile – it can be folded during the crafting process to create a wavy, eye-catching pattern called Damascus, which is both beautiful and functional. So, it’s not just strong and sharp but also has a unique, decorative look.

Spring Steel

Spring steel is a favorite for making swords, especially among experts, because it’s really tough and flexible.

It’s great for various swords, like samurai swords. What’s special about it is that it can bend a lot and still go back to its original shape.

To make spring steel, different kinds of steel with low to high carbon content are processed to be really strong.

5160

5160 spring steel is popular for long swords due to its durability and cutting strength. It contains about 0.60% carbon and a little chromium, making it hard and resilient.

This quality is why renowned swordsmiths prefer it, especially for its excellent shock absorption, although it does cost more.

Similar to 1060 steel but stronger due to chromium, 5160 is ideal for large, flexible swords that need to be tough.

Swords made from 5160, like long Longswords or curved Katanas, are known for lasting durability, maintaining a sharp edge, and absorbing shock well.

5166

5166 spring steel is similar to 5160 but includes manganese, making it stronger and more flexible, and slightly better at resisting wear.

Its higher carbon content, at 0.66%, combined with manganese, enhances its durability and hardness.

This makes it ideal for frequent sword use, offering increased longevity and quality.

9260

9260 Spring Steel, or Manganese Steel, is highly flexible due to its 2% silicon content, able to return to shape even after a 90-degree bend.

While durable, it requires careful use to avoid breaking. Its production needs advanced skills, making it more expensive but offering good value for its sharpness and flexibility.

EN45

EN45 spring steel, much like 9260, excels in flexibility due to its high silicon content. Originally used for car leaf springs, this feature also makes it great for sword blades.

Properly treated, EN45 matches 9260 in flexibility and shock resistance, making it a reliable choice for crafting strong, high-quality swords. It’s a favored material in the bladesmithing industry alongside 9260.

EN42J

EN42J steel is quite similar to 9260 spring steel, known for its great flexibility, which comes from the silicon added to its mix.

This type of steel is often used for Japanese swords like Katanas. It’s easier to work with and doesn’t require highly experienced swordsmiths, making it both durable and affordable.

This makes EN42J a popular choice for those looking for a good quality sword without a high price.”

65Mn

65Mn Chinese Steel is a kind of spring alloy known for its high resilience. It has a high carbon content, around 0.62 to 0.70%, and a good amount of manganese, between 0.9 to 1.2%.

These elements make the blade both hard and tough, yet it remains flexible enough to be classified as spring steel. It’s often compared to the 5160 Spring Steel because they share similar qualities.

Tool Steel

Tool steel blades stand out for their exceptional toughness and ability to maintain sharpness under heavy use.

Originally for making tools, they resist wear well and keep their shape even at high temperatures. Swordsmiths favor tool steel for strong, battle-ready swords, although they’re less flexible.

They handle pressure and repetitive impacts well, making them ideal for broad swords like Dadao or Falchion, and also for sturdy Katanas or Jian swords

L6 Bainite

L6 steel is tough to work with, leading to its high cost. Once processed, it yields an extremely durable blade, thanks to its high nickel content.

This makes it suitable for demanding tasks. L6 Bainite, created by heating the steel at specific temperatures, is one of the strongest blades available.

While ideal for heavy-duty use, it requires regular upkeep similar to 1060 steel. L6 steel is commonly used in high-end replica swords like Katanas, typically priced over $1,000.

S7 Shock

S7 Shock tool steel is an upgrade from L6 Bainite, placing it higher in both price and rarity. Not many bladesmiths work with it due to its complexity.

Known for outstanding strength and durability, it’s used in crafting shorter swords that can withstand a lot of impact without bending much.

These qualities make it especially suitable for intense situations like survival scenarios, where a blade needs to stay sharp and effective through heavy usage.

Sleipner

Sleipner steel, developed as an improvement over the commonly used D2 steel for knives, combines high hardness with a stable, durable edge.

It excels in wear resistance and can endure considerable impact. While not widely popular, it’s occasionally chosen for crafting shorter swords, leveraging its robust qualities.

T10

T10 is a Chinese alloy tool steel commonly used in making Chinese or European swords. Similar to the 1095 steel but with added silicon, it maintains strong edge retention and hardness.

The variety of alloys in T10 can create unique patterns like a hamon line on the blade. The “T” stands for tungsten, enhancing the steel’s resistance to scratches and abrasions.

Its high carbon content makes it great for effective cutting, contributing to its popularity in Chinese swords like the Niuweidao and Liuyedao.

K720

K720 steel, also known as Bohler Tool Steel, is a high-carbon tool steel known for its toughness and strength.

It’s oil-hardened and can be sharpened to a very fine edge while maintaining its toughness, even during cutting tasks.

However, its low chromium content makes it more prone to rust, especially when exposed to moisture. Consequently, it requires considerable maintenance and care to prevent rusting.

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is commonly chosen for making decorative swords rather than knives or daggers. Its high chromium content makes it highly resistant to rust, ideal for display blades.

However, this same property can make the steel brittle, unsuitable for cutting or functional use, as it can break easily.

For this reason, some sword enthusiasts don’t regard them as “real” swords.

In contrast, smaller items like the Ko-Tanto (small Japanese dagger), can have functional stainless steel blades, similar to many small kitchen knives.

Manganese

Manganese swords, while rare, are valued for their uniqueness.

Their high manganese content makes them both brittle and flexible, limiting their use to light cutting practice or as decorative pieces, suitable for novice swordsmen.

Niolox

Niolox is a stainless steel often used as an alternative to ATS-34. It’s well-suited for smaller daggers or knives, offering good toughness and edge retention.

Although resistant to corrosion, it’s less popular for larger blades or cutting practice knives.

K120C

K120C is a special kind of powder steel from Japan, licensed by a Swedish company, SSAB. Imagine it like a cake mix with evenly spread ingredients; this steel has its carbon spread out evenly too.

This even spread helps make the steel strong and consistent when it’s shaped and hardened.

It’s similar to the well-known 1095 high carbon steel, known for keeping a sharp edge and being durable. In short, K120C steel is great for making blades that perform well and stay sharp.

Q235

Q235 steel from China is often used for making swords that are easy on the wallet. Think of it like stainless kitchenware: it’s good at avoiding rust but not the best for cutting.

This makes it a nice option for beginners who want a decorative sword without spending much.

3CR13

An upgrade from the Q235 is the 3CR13, which is also a type of stainless steel that is rust-resilient, but much tougher than its predecessor.

It is also very affordable and makes for a great decorative blade for beginners or LARP enthusiasts.

2CR13

2CR13 steel is quite similar to 3CR13 but has a bit less carbon. This makes it more like stainless steel, better at resisting rust.

It’s good at staying sharp and is affordable, but it’s not typically used for big swords. Instead, it’s great for smaller, practical blades like a Kukri or a Bowie knife.

420J2

The 420J2 is a kind of stainless steel that’s great at avoiding rust and lasts long. It’s often chosen for decorative swords.

Unlike other stainless steels, you can sharpen 420J2 easily, but it doesn’t stay sharp for very long. Still, it’s perfect for blades that are meant to be displayed or hung up as decorations.

420HC

420HC stainless steel is one of the top choices for stainless steels. It’s often used for small daggers or kitchen knives because it has a lot of carbon.

This means the blade fights off rust well and stays sharp and tough. Generally, 420HC is more expensive and is found in fancier decorative swords.

440C

440C stainless steel is often incorrectly labeled in the market. It has a lot of chromium, which helps it resist rust.

There’s also a good amount of carbon, so it can be sharpened and used for simple tasks.

But, it’s not made for fighting. It’s more of a decorative piece, good for things like cutting paper. This is why it’s usually in a higher price range.

AUS-6-8-10

AUS-6 is a Japanese steel with 0.6% carbon. It makes a tough blade, usually about mid-level hardness. It sharpens well but needs regular care after use.

AUS-8 is favored by custom knife makers for its toughness, sharpness, and higher hardness. AUS-10, with more carbon, is even harder.

It’s tougher than AUS-8 but might rust a bit more easily than 440C steel. However, it stays strong and sharp longer.

Folded

Folded swords come from a detailed forging process, not from a specific steel type. This involves repeatedly folding the steel to remove flaws, creating durable and flexible blades.

Contrary to popular belief, folding a sword more than 20 times can weaken it.

While these swords are visually appealing, they aren’t stronger than modern single-piece steel blades.

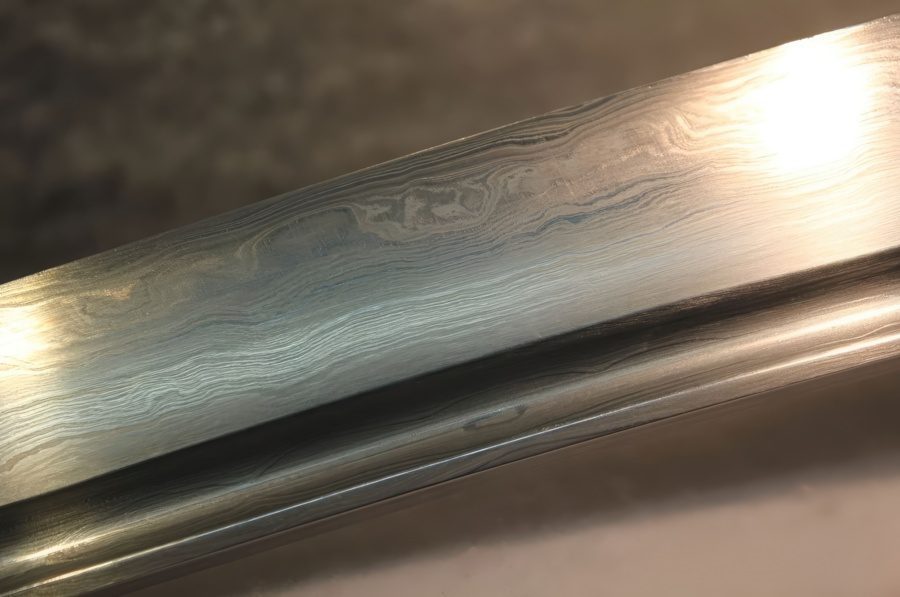

Damascus Steel

Damascus steel swords combines different steels into a single blade, creating distinct patterns.

Acid treatment enhances these patterns, giving the steel a mystical appearance popular among sword enthusiasts.

Despite its beauty, Damascus Steel isn’t as strong as modern single-type steel due to potential air pockets from folding.

While valued by collectors for its aesthetic and traditional craftsmanship, it’s best suited for decorative use rather than functional cutting.

Tamahagane Steel

Tamahagane steel, crafted from Japanese iron sand, is expensive but not the strongest. Its intricate folding process creates attractive patterns but makes the blade more fragile compared to modern steel.

Used mainly in traditional Japanese swords, these can cost upwards of $3,000. A Chinese Sword variant, used in less expensive swords around $800, offers better cutting strength but requires regular maintenance.

Laminated

Laminated steel, a traditional Japanese technique, combines different steels in a single blade, not through folding, but by welding them together.

This method, used in Katanas, mixes hard and soft steels to optimize the blade, offering both flexibility and a sharp edge.

It’s a strategic way to bring out the best qualities of each steel type in the finished blade.

Alloy & Other

To make a sword that’s good for cutting, carbon is essential. But using only carbon steel might not be enough.

During production, adding metal alloys like silicon, manganese, and chromium to the carbon blade gives it special qualities.

These alloys, found in types like spring and tool steel, improve the blade’s resistance to wear, rust, and improve its toughness, flexibility, and strength.

Some alloys even offer additional benefits, making the steel more effective.

San Mai

San Mai is a metalworking technique where a blade is made with three layers. The edge is hard steel, surrounded by softer iron or stainless steel on both sides.

This method gives the blade both hardness and flexibility.

Some San Mai blades mix spring steel and tool steel, creating a unique and effective metal alloy for blades.

Wootz Steel / Crucible Steel

Wootz steel, known for its unique making technique, was lost around the 17th or 18th century. It was the original material for what’s now called “Damascus Steel.”

Finding such a blade today is extremely rare. Although the exact method of making Wootz Steel was lost, some manufacturers have managed to imitate its distinctive patterns.

HWS-1S Alloy

The HWS-1S steel, a trade secret of the Hanwei sword company, has an undisclosed composition.

It’s recognized for its performance, durability, and ability to maintain a sharp edge.

A key feature of this steel is its differential tempering, resulting in a striking hamon or blade pattern.

HWS-2S Alloy

The HWS-2S alloy, another trade secret from Hanwei, is a less expensive alternative to the HWS-1S.

Like its counterpart, it undergoes differential tempering and features varying carbon content along the blade. Swords made from this steel are functional for cutting.

Aluminum

Aluminum is a light, recyclable metal used for making practice swords like the Japanese Iaito. They are affordable and shiny, popular with collectors and martial arts beginners.

But, they wear out quickly and can’t be heat-treated, making them less sharp.

They’re good for beginners but not ideal for advanced use or long-term collecting.

Synthetic

Synthetic sword blades, made from synthetic materials or sheet steel, are light and easy to move.

They’re often used by beginners for practice and sparring. Even though they seem safer, it’s important to always be careful.

People sometimes think synthetic swords won’t cause harm, but this can lead to more injuries in HEMA (Historical European martial arts) training.