Types of Bo-Hi (Grooves) and Their Attributions for Katanas

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Hi (grooves) found on Japanese blades are not only highly functional but also serve as indicators of the blade’s swordsmith, swordmaking school, or production time, making it crucial in sword appraisal. These grooves vary greatly in shape, ranging from wide to very narrow, having shaped ends, or being carved into the tang without a finished end.

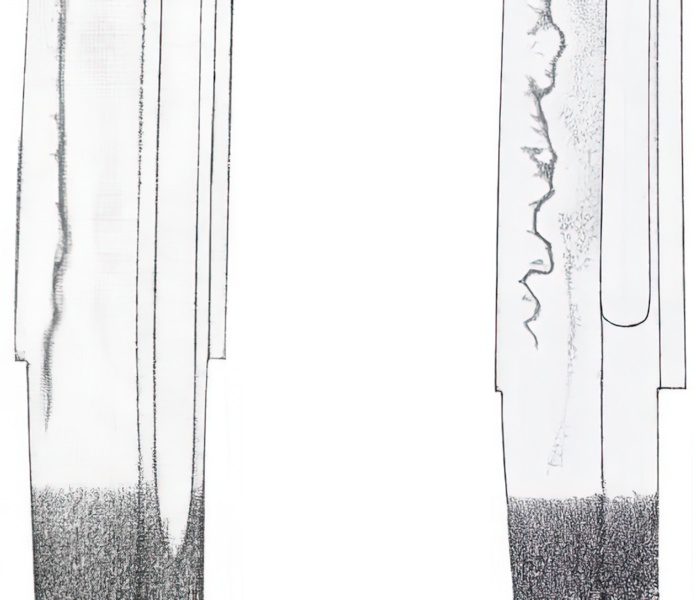

Different Types of Hi (Grooves)

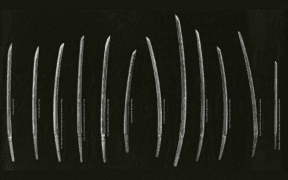

In Japanese sword appraisal, the swordsmith, school or tradition, and the age of the blade are determined based on its appearance. Generally, the hi (grooves) and their features are examined when evaluating the blade shape (sugata).

Hi vary in shape, with specific grooves associated with particular swordsmiths and swordmaking traditions. However, some grooves were added later and are referred to as ato-bi (後樋). The grooves are only considered indicators in sword appraisal when they are original to the blade.

For a comprehensive list of swordsmiths and schools, the book The Connoisseur’s Book of Japanese Swords by Kōkan Nagayama serves as a valuable reference.

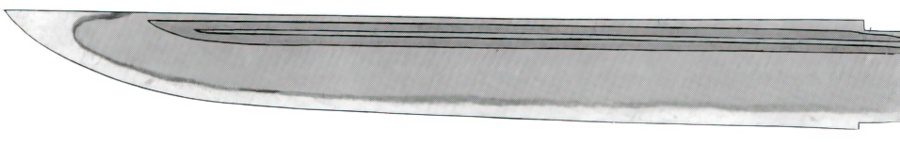

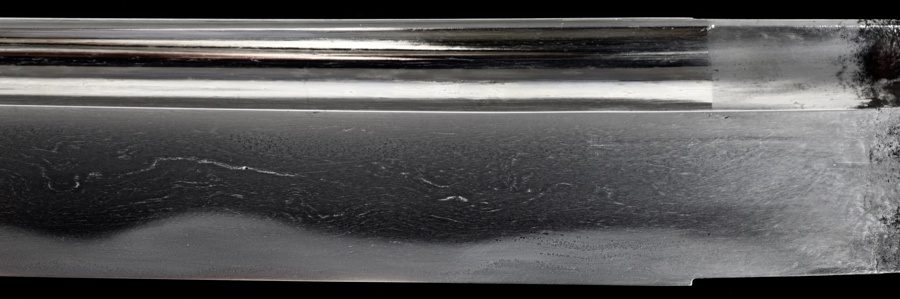

1. Bo-hi (Straight, Wide Groove)

Also spelled bo-bi, a bo-hi (棒樋) is a long, straight, wide groove. As a long and wide groove, it takes most of the shinogi-ji, which is the surface between the ridge line and the back of the blade. However, when a long, wide groove is carved into a tanto or a specific type of wakizashi, such as hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi, the term katana-hi (刀樋) applies.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Bo-hi is the most common type of groove used by several swordsmiths and schools, making it impossible to provide representative names.

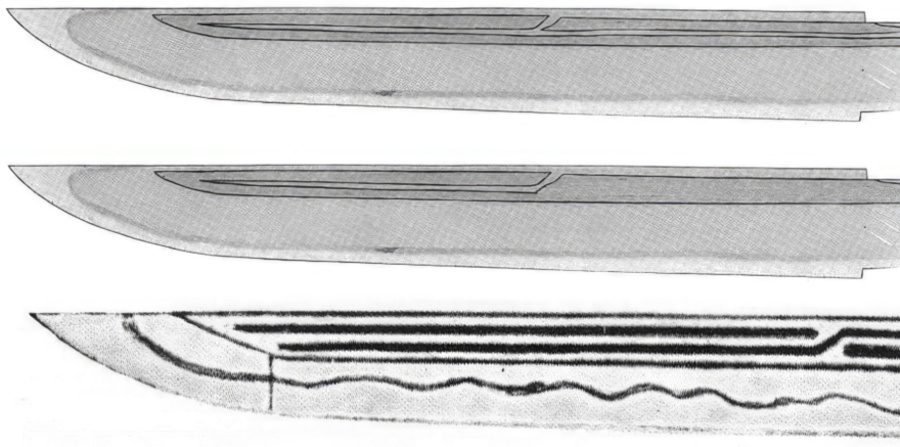

2. Bo-hi with Soe-bi

Bo-hi with soe-bi (棒樋に添樋) refers to a straight, wide groove (bo-hi) accompanied by a second, thinner groove (soe-bi). Its thinner groove lies along the wider groove and can either be located at the ridge line (shinogi), on the flat surface between the ridge line and the back (shinogi-ji), or slightly under the shinogi-ji.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Bo-hi with soe-bi was more or less introduced by the Bizen swordsmiths of the Nanbokucho period, with this style being most popular during the Muromachi period.

Notable swordsmiths known for incorporating this groove in their blades include Nobukuni, Sanjo Yoshinori, Horikawa Kunihiro, Miyoshi Nagamichi, Echizen Kanenori, and Yamashiro no Kami Kunikiyo. Schools applying this type of groove include the Hasebe, Sue-Shikkake, Kanabo, Takada, Sue-Mihara, Hojoji, etc.

3. Bo-hi with Tsure-bi

Bo-hi with tsure-bi (棒樋に連樋) refers to a straight, wide groove (bo-hi) accompanied by a second, thinner groove that extends to the top of the bo-hi. In this case, the thinner groove extends around the front of the wider groove and towards the back surface of the blade.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Bo-hi with tsure-bi became more popular towards the end of the Muromachi period, but was also found on blades of famous Kamakura and Nanbokucho-period swordsmiths.

Koto-era smiths like Nobokuni, Sukezane, Kagemitsu, Sanenaga, and Kanemitsu incorporated this groove into their blades, as did Shinshinto-era smiths like Suishinshi Masahide and Taikei Naotane. Schools known for applying this groove into their works include the Rai, Ko-Osafune, Horikawa, Hojoji, etc.

4. Futasuji-hi (Double Bo-hi)

Futasuji-hi (二筋樋) refers to a pair of identical and parallel grooves, but not necessarily of the same length. It is also known as nihon-bi (二本樋).

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Futasuji-hi emerged towards the end of the Kamakura period, though earlier swords with this type of groove were probably added on a later date (ato-bi).

Famous swordsmiths known for incorporating futasuji-hi include Rai Kuninaga, Sadamune, Nobukuni, Kaneuji, Kanemitsu, and Izumi no Kami Kanesada to name a few. Swordmaking schools, like the Sengo, Sue-Aoe, Yasutsugu, Hojoji, also applied the groove on their works.

5. Take-kurabe

The term take-kurabe (丈比べ) translates as comparison of height. It is a variant of futasuji-hi, in which one thin groove ends noticeably before the other. It was found on some wakizashi or tanto, particularly on hira-zukuri blades without ridge lines.

6. Shobu-hi (Iris Leaf-Shaped Groove)

Another variant of the futasuji-hi, the shobu-hi (菖蒲樋) resembles an iris, as the two small grooves merge at the tip. It can be found on tanto blades of Yamato and Soshu provinces.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: The shobu-hi was incorporated into blades by swordsmiths such as Rai Kunimitsu, Takagi Sadamune, Awataguchi Norikuni, Hiromitsu, as well as by the Shikkake and Miike schools.

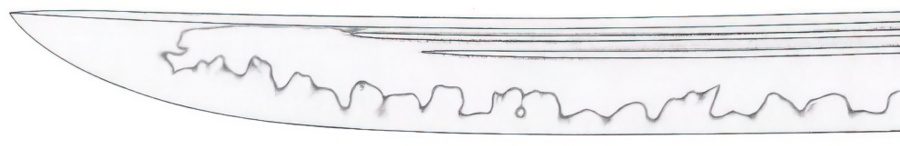

7. Kuichigai-hi

The kuichigai-hi (喰違い樋) refers to two thin grooves, in which the top groove ends at the middle of the blade, while the bottom groove continues, surrounding the shorter groove. Sometimes, the top groove is interrupted at the middle, while the bottom groove widens into a large groove. In some cases, the thin grooves are crossing somewhere along the blade.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Famous swordsmiths who incorporated kuichigai-hi on their works include Nobukini, Heianjo Nagayoshi, Dewa Daijo Kunimichi, Taikei Naotane, and Gassan Sadakazu, to name a few. Schools such as Hosho, Sue-Tegai, Kanabo, Uda, Koga, and Yasutsugu also used this type of groove.

8. Koshi-hi

Also pronounced as koshi-bi (腰樋), a koshi-hi is a short groove with a rounded top, carved on the lower section of the blade, near the tang. More often, it is only carved on the front of the blade. This feature was commonly seen on tanto, and occasionally on certain Koto-era tachi and katana.

Sometimes, the koshi-hi is combined with the gomabashi (護摩箸), which is a shorter variant of parallel grooves (futasuji-hi). Gomabashi was mostly seen on ko-wakizashi or tanto and rarely on tachi and katana.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Famous swordsmiths who applied a koshi-hi on their works include Nobukuni, Heianjo Nagayoshi, Shintogo Kunimitsu, Yasutsugu, Sagami no Kami Masatsune, Kanenori, Suishinshi Masahide, and Taikei Naotane, to name a few. Swordmaking schools such as the Awataguchi, Rai, and Horikawa used both the koshi-hi and the gomabashi.

9. Naginata-hi

A naginata-hi (薙刀樋) refers to a short wide groove (bo-hi), mostly accompanied by a thinner groove (soe-bi), that ends early in a diagonal manner.

The naginata-hi is named after the Japanese polearm naginata, which almost exclusively-made with this type of groove. However, the earliest known Japanese sword with such grooves is the Kogarasu Maru (小烏丸), which is double-edged at the tip. The naginata-hi was sometimes found on some tanto, wakizashi, and katana blades.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Famous swordsmiths who applied the naginata-hi to their blades include Nobukuni, Heianjo Nagayoshi, Hojoji Kunimitsu, Kurihara Nobuhide, Suishinshi Masahide, Taikei Naotane, and Gassan Sadakazu. Schools such as the Kanabo, Sue-Seki, Uda, and Horikawa incorporated the groove into their works.

Surprisingly, the naginata-hi can also be found on some Chinese swords, so some speculate that the groove may have been originally Chinese.

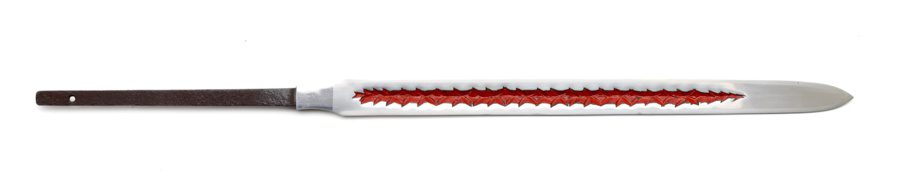

10. Kusabi-hi

The term kusabi-hi (楔樋) translates as wedge groove. It is one of unusual type of grooves found on some spearheads, particularly on some forms of yari used by some samurai and soldiers. The kusabi-hi can be found on some large spearheads with parallel sides and triangular cross-section. In some cases, these irregularly-cut grooves are highlighted with red lacquer.

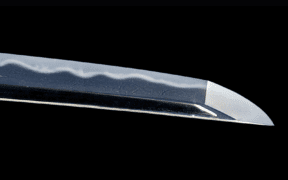

Types of Tome (Groove End)

When it comes to hi (grooves), the term tome (留め) means stop, referring to the bottom of the groove near the tang. In sword appraisal, it is examined how a groove ends, as some run into the tang, while others end above it.

1. Kaki-toshi

The term kaki-toshi (書き通し) means no end, referring to a groove-end that is cut all the way through the full length of the tang.

2. Kaki-nagashi

The term kaki-nagashi (書き流し) means halfway end, referring to a groove-end that extends and tapers halfway down the tang. Generally, a kaki-nagashi does not have a crisp and clear end, but it tapers out gradually into the body of the tang.

3. Kaku-dome

The term kaku-dome (角留め) means square end. Most of the time, this groove-end finishes around an inch from the notches (machi) or just above the tang in an angular manner.

However, in case the groove ends within the tang with a distinct kaku-dome the same way it would have stopped before the notches, it may still be considered as a kaku-dome. It differs from the usual kaki-nagashi, which gradually and smoothly extends into the body of the tang.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: The kaku-dome can be seen in the blades of famous swordsmiths like Tomonari, Nagamitsu, Kagemitsu, Shimada Yoshisuke, Dewa Daijo Kunimichi, Yokoyama Sukesada, Taikei Naotane, and Gassan Sadakazu. Also, some schools, such as Oei-Bizen, Tegai, Takada, and Hojoji, incorporated the kaku-dome into their works.

4. Maru-dome

The term maru-dome (丸留め) means rounded end, referring to the end of the groove finished with a round and even surface. It often stops above the tang on the polished portion of the blade and can be seen on various types of hi, including bo-hi with soe-bi, naginata-hi, and such.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: Bizen swords of the mid-Kamakura and Muromachi periods often feature a maru-dome. It is important to note that the maru-dome executed by swordsmiths Kanemitsu and Kagemitsu was typically positioned higher than that of other smiths. Additionally, famous swordsmiths such as Nobukuni, Heianjo Nagayoshi, and Echizen Yasutsugu incorporated it into their works, as did schools like Sue-Tegai, Kanabo, and Horikawa.

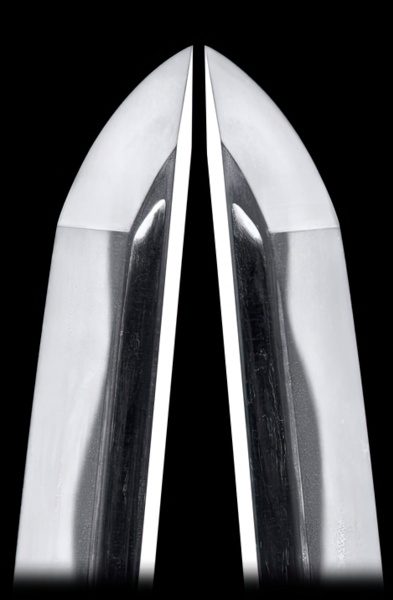

Types of Hisaki (Groove Tip)

The tip of the hi (groove) is called the hisaki (樋先), located near the point area of the blade. In sword appraisal, it is examined how the groove ends towards the tip of the blade, as certain swordsmiths and schools favored specific types of hisaki.

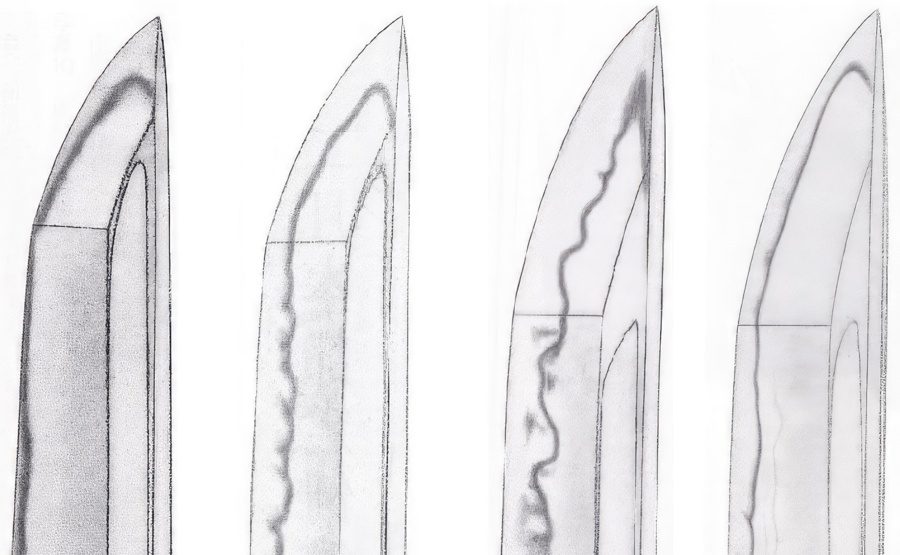

1. Hisaki-agaru (Rising Hisaki)

The hisaki-agaru (樋先上がる) refers to a groove that is more or less close to the ko-shinogi and extends beyond the yokote. Technically, the ko-shinogi is the diagonal line that separates the point area of the blade from the back. In contrast, the yokote is the perpendicular line to the cutting edge, distinguishing the point from the body of the blade.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: The hisaki agaru is popular on Koto blades and rarely on Shinto blades. Famous swordsmiths associated with incorporating the rising hisaki on their blades include Nobukuni, Kagemitsu, Kunimune, Suishinshi Masahide, Taikei Naotane, and occasionally Echizen Yasutsugu, Tadayoshi, and Horikawa Kunihiro. Schools associated with hisaki agaru include the Rai, Ko-Bizen, Ichimonji, and Ko-Osafune.

2. Hisaki-sagaru (Descending Hisaki)

The hisaki-sagaru (樋先下がる) refers to a groove that stops below the yokote, which is the line perpendicular to the cutting edge that separates the point area from the body of the blade.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: The hisaki-sagaru was mostly seen on Nanbokucho-period swords and Satsuma-province swords. Famous swordsmiths who incorporated the descending hisaki into their blades include Go Yoshihiro, Dewa Daijo Kunimichi, Tadayoshi, and Sa Yukihide. Schools such as Tegai, Shikkake, Chogi, Sue-Aoe, and Hojoji also incorporated the hisaki-sagaru into their works.

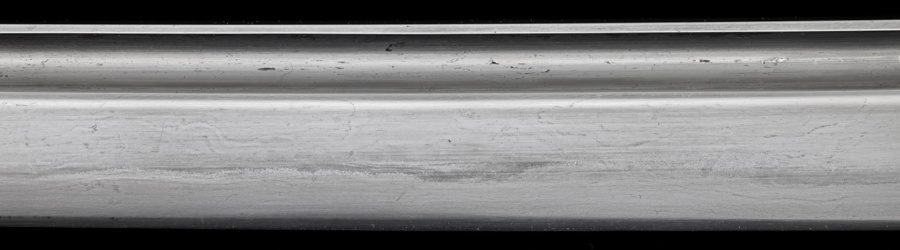

Types of Chiri (Groove Wall)

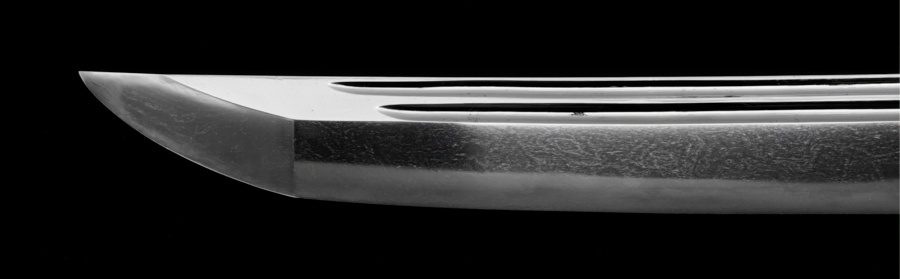

The term chiri (written as チリ or 散) literally means wall of the groove. In sword appraisal, particular attention is given to the chiri, especially when the blade is in shinogi-zukuri style, characterized by a distinct ridge line (shinogi).

When a wide groove is carved on a shinogi-zukuri blade, a very narrow flat surface (shinogi-ji), known as the chiri, may remain on one or both sides of the groove.

1. Ryo-chiri

The term ryo-chiri (両チリ) means two walls, referring to the remaining flat surface (shinogi-ji) on both sides of the groove. This occurs when a wide groove is carved at the center of the shinogi-ji, leaving a chiri along the ridge line (shinogi) and towards the back (mune) of the blade.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: The ryo-chiri was often seen in schools outside the Gokaden (The Five Traditions). It was commonly found in the blades crafted by swordsmiths from the provinces of Kaga, Echizen, Hoki, and Iwami. While it became rare after the Koto era, the ryo-chiri occasionally appeared in the works of swordsmiths such as Ogasawara Nagamune, Higo Daijo Sadakuni, and Echizen Daijo Tadakuni.

2. Kata-chiri

The term kata-chiri (片チリ) means one wall, referring to the remaining flat surface (shinogi-ji) on one side of the groove. It happens when the wide groove is carved directly along the ridge line (shinogi) and leaves only a chiri towards the back (mune) of the blade.

Related swordsmiths and swordmaking schools: The kata-chiri was popular with all Koto-era schools, though it was used less often during the Shinto era. It was seen in the blades of swordsmiths Yokoyama Sukesada, Ichinohira Yasuyo, Suishinshi Masahide, Taikei Naotane, and Gassan Sadakazu.