How Japanese Swords Played a Role in World War 2

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Despite Japan’s modernization of its military forces in 1868, officers were still required to carry a traditional Japanese sword as a reminder of their heritage and culture. This resulted in a large number of swords being made between the end of the Meiji era (1868-1912) to the end of World War II (WW2) in 1945.

This article explores Japanese swords that were used in WW2, their characteristics, and their roles in history.

Brief History & Terminology

During the Meiji era, the Hatorei Edict prohibited the wearing of swords in public, resulting in many sword makers going out of business.

As Japan’s military institutions grew rapidly in the early 20th century, there soon was a dwindling supply of shinshinto swords (new-new swords made between 1781 and 1876).

By 1933, military organizations made efforts to train and support smiths who could make traditional Japanese swords—some of which led to the founding of Yasukuni Tanren Kai on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine.

Many simple blacksmiths were also recruited to meet the growing demand. Although some traditional Japanese swords were produced, a large number of guntō (military swords) were produced using Western steel or salvaged steel from railroad tracks or structures.

These non-traditionally made swords are known as shōwatō.

Kyū Guntō (旧軍刀)

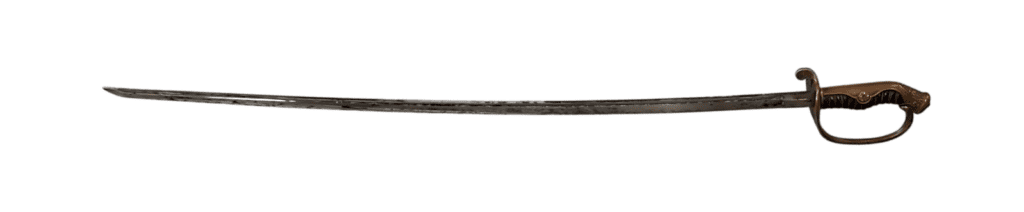

Kyū guntō (old military swords) were used in early World War II by Japanese navy and army officers but were phased out by the mid-1930s in favor of the newer models.

Heavily influenced by Western military swords, they are similar in design to European sabers and often feature a D-guard. Most are made from modern steel with scabbards that may include chromed metal, lacquered wood, or brass fittings.

Type 19 Kyū Guntō

Mainly wielded by army officers, the type 19 kyū guntō was adopted in 1886 and used until the 1930s. It featured a straight blade with a Western-style hilt.

Type 25 Kyū Guntō

The type 25 kyū guntō is a modified version of the type 19, used primarily by naval officers. Its differences are subtle in terms of fittings and hilt design.

Shin Guntō (新軍刀)

Used between 1935 to 1945, shin guntō are the most common swords used in WW2. The shift from kyū guntō to shin guntō occurred as an effort to boost Japan’s national pride and revive traditional samurai aesthetics.

Styled after the tachi, a sword common during the Kamakura period (1185-1332), colored tassels attached to the end of the sword hilt indicated the officers’ ranks. Due to the sheer number of swords required, shin guntō was rarely hand-forged.

Type 94 Shin Guntō (九四式軍刀)

Introduced in 1934 for commissioned officers, the type 94 shin guntō was the first to adopt a design similar to traditional samurai swords, featuring a handle covered in samegawa (ray skin) and tightly wrapped with silk tsuka-ito (handle wrap). This sword usually had a metal scabbard with a protective wood lining and cherry blossom motifs on the sword fittings.

Type 95 Shin Guntō (九十五式軍刀)

Designed for non-commissioned officers (NCOs), the type 95 shin guntō released in 1935 resembles the type 94, but is cheaper to produce. The blades had bohi (fullers) with a serial number stamped on it along with brass guards.

Unlike the officer’s sword, the hilts were made of copper or aluminum and simply painted to resemble the traditional swords.

By 1945, due to wartime shortages, a simplified version was made, featuring a wooden hilt with cross-hatched grooves, wooden scabbards, and iron fittings.

Type 98 Shin Guntō (九八式軍刀)

As resources became scarce, the type 98 shin guntō was the new standard for officers from 1938 onwards. Initially, the differences were subtle. Towards the end of the war, these swords were made with simpler materials using cheaper fittings and wooden scabbards.

Kai Guntō (海軍刀)

Introduced alongside the shin guntō was the kai guntō, a version specific to the Japanese Imperial Navy. Blades for the kai guntō may be machine or traditionally made.

Those with stainless steel blades were mostly machine-made at the Tenshozan Tanrenjo in Kanagawa Prefecture and feature an anchor stamp. Others were made by the Toyokawa Naval Arsenal.

There were two main designs for kai guntō. Like the shin guntō, these were the type 94 and 98. Since kai guntō was only for officers, there were no type 95 versions.

Type 97 Kai Guntō

Another less common version is the type 97 kai guntō, similar in design to types 94 and 98. However, these were often higher quality swords with features such as custom fittings with family crests and stainless steel blades for better corrosion resistance, tailored for higher ranks such as admirals.

Ancestral Blades

Besides the swords mentioned above, there were also some ancestral blades or family swords that were refitted to be used during WW2. These were more common among higher-ranked officers with ancestors who may have been samurai.

After the war, Japanese soldiers were required to surrender all their swords. Over the years, there have been cases where these ancestral blades have been returned to their families.

Conclusion

Today, although many of these swords are not viewed as traditional “art swords,” they still carry significant historical and cultural importance. While they may not be valued for their craft, these Japanese guntō are valued by collectors and historians for their connection to Japan’s past.

Worth mentioning that we covered the most important types of swords, but we may have missed a few lesser-known ones, as well as daggers and bayonets. If you’d like to explore all of them, we recommend checking out our full index of Japanese sword types.